As we continue to tour the public spaces at Optima communities to highlight the impeccably-curated collection of Modernist furnishings, it is always a delight to set our sights on Tulip tables, designed by the luminary architect, Eero Saarinen.

Eero Saarinen (1910-1961), the Finnish architect who conceived the St. Louis Gateway Arch, along with many other well-known structures including the Washington Dulles International Airport, also received enormous recognition for his modernist furniture designs produced by Knoll, including the Womb™ Chair.

Legend has it that Saarinen approached Florence Knoll in 1955 with his desire to explore new approaches to furniture design, evolving from his background in sculpture and a desire to create a table with a single leg.

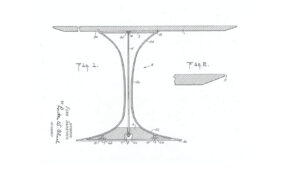

So in the late 1957, Saarinen proved true to his word and broke tradition by introducing a collection of tables, initially referred to as Saarinen Tables. They feature a single central base, made from single pieces of cast aluminum and finished in black, white or platinum, that appeared to “grow like a flower” with a stem-like base, as opposed to having the more traditional standing legs. With this simple, organic shape that included a slender neck and elegant, organic proportions, the base became the focus of a large series of tables that came to be known as Tulip Tables.

With options for circular and oval tops with tapered edges in a variety of sizes and heights, Tulip Tables were conceived from an integrated design framework that supports a cohesive human experience. They were an immediate hit once they became commercially available, in part because the single base provides visual lightness while inviting people to gather around a table unencumbered by legs. Tulip Tables delighted both residential and commercial furniture buyers with an array of color choices as well, with tops constructed of laminate or wood veneers, or made from natural materials like granite or coated Arabescato marble.

While design trends come and go, a precious few furniture pieces remain timeless and iconic. Saarinen’s Tulip Tables are among those — ever-elegant, minimal and sophisticated.