As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re celebrating the incredible work of Itsuko Hasegawa, a trailblazer in the worlds of design and architecture. Hasegawa’s unique blend of traditional Japanese elements and modern design techniques has established her as a leading figure in the architectural realm, inspiring us with her innovative and thoughtful creations.

The Life of Itsuko Hasegawa

Born in 1941 in Yaizu, Japan, Itsuko Hasegawa was raised in a post-war era brimming with opportunities for growth and innovation. Hasegawa’s early life was marked by an exposure to education, a privilege that paved the way for her future achievements. After graduating from Kanto Gakuin University in 1964, she further honed her skills at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. It was during this period that Hasegawa’s architectural philosophy began to take shape, influenced by both modern advancements and the rich tapestry of traditional Japanese design.

A pivotal moment in Hasegawa’s early career was her time working with the renowned architect Kiyonori Kikutake, a leading figure in the Metabolist Movement. This experience significantly impacted her design approach, blending modernist techniques with an inherent appreciation for natural and cultural harmony.

Notable Works and Achievements

In 1979, Hasegawa established her own firm, Itsuko Hasegawa Atelier, marking the beginning of a series of groundbreaking projects that would define her career. Her work is characterized by a deep sensitivity to the environment and a unique understanding of space.

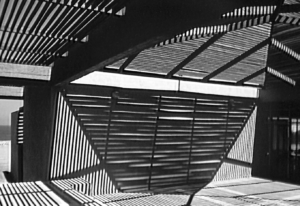

One of Hasegawa’s most acclaimed projects is the Shonandai Cultural Centre in Fujisawa.

Built in 1987, this cultural hub is a testament to her ability to create dynamic and fluid spaces that resonate with the community. The build features a mixture of various forms, including two domed structures and a scattering of hut-like forms that resemble flowers blooming and defy traditional architectural arrangement.

Another significant work is the Sumida Culture Factory in Tokyo, a project that underscores her commitment to functional and engaging public spaces. Built in 1994, the complex acts as another example of Hasegawa’s creation of a landscape. The factory features various interconnected design elements, including a grand dome and two defining catenary roofs.

Her contribution to architecture has been recognized with several awards, including the Architectural Institute of Japan’s Design Prize for the Brizan Hall, the Japan Cultural Design Award, the Japan Art Academy Award and the prestigious Royal Academy of Art’s Architecture Prize.

Hasegawa’s influence extends beyond her architectural projects. Her roles as a professor and lecturer in various international institutions have allowed her to impact the next generation of architects, advocating for greater diversity and creativity in the field.

Itsuko Hasegawa’s journey is not just about building structures; it’s about building dreams and inspiring change. Hasegawa’s legacy is a powerful reminder of how architecture can transcend mere buildings to become a medium for cultural expression and community engagement.