In our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re highlighting Elizabeth Diller, a visionary who turns metaphors into brick and mortar and continues to challenge conventional architecture.

The Life of Elizabeth Diller

Elizabeth Diller was born in 1954 in Łódź, Poland, and moved with her parents, who were Holocaust survivors, to the United States when she was six. She was deeply affected by the social unrest of the late 1960s, which ultimately led her to enroll in the Cooper Union School of Architecture in 1970 which, at the time, was a creative hotbed and home to avant-garde design.

Initially, Elizabeth intended to pursue art or filmmaking, but ultimately found herself captivated by alternative methods of space-making. Even then, she was much more interested in the East Village music and art scene than in her classes. It wasn’t until Elizabeth met one of Cooper Union’s design professors, Ricardo Scofidio, that she became fully invested in design. After graduation, Diller and Scofidio became both romantic and creative partners, and emerged as prominent conceptual artists, focusing on comically dark design hacks and advancing the idea that “anything can be architecture” in their 1994 book, Flesh. This conceptual approach that challenged traditional architecture also earned them the coveted MacArthur Fellowship (known as the “Genius Grant”) in 1999.

Notable Works

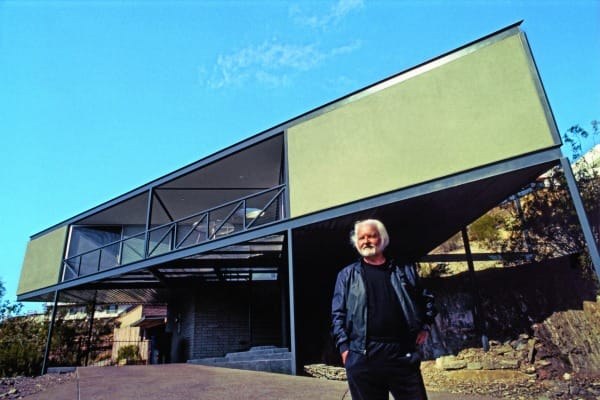

By 2000, Diller Scofidio projects were gaining considerable traction and scale, as demonstrated by their design for the Blur Building at the Swiss Expo in 2002. Utilizing a cloud of mist produced by 31,500 high-pressure nozzles over Lake Neuchâtel, this project encapsulated the team’s belief that architecture isn’t just about concrete unmovable structures, but can be an immersive, sensory experience. And as the partnership expanded to include Charles Renfro, the trio transformed the very essence of what a building could represent.

In 2006, their firm took on the ambitious project of renovating a historic elevated train line in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. The result? The High Line, an urban park that floats amidst the skyscrapers, becoming an iconic piece of the city’s architectural landscape.

During the 2010s, Diller’s stature in the world of architecture expanded greatly as the firm undertook a host of ambitious, institutional and municipal projects, culminating in designing a massive extension to New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2019 as spaces for modern and contemporary installations. Beyond allowing the museum to grow its exhibition footprint, this project redefined urban space, blurring the lines between public and private, museum and city.

Just north of Chelsea, this stunning structure boasts a movable shell, allowing it to be reconfigured based on how the interior space is programmed. More recently, the team has undertaken numerous cultural and institutional projects, including the London Centre for Music and revitalizing the historic Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center, further securing a place for Diller and her partners in the architectural canon by creating a new language of contemporary design.

Elizabeth Diller’s journey redefines the essence of architecture, merging innovation with functionality. Her transformative works extend beyond physical spaces to influence the cultural fabric of society. And her legacy is not solely in the impressive silhouettes of her buildings but in the way she inspires future generations to envision and craft the world anew.