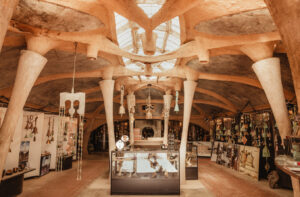

At Optima, our commitment to crafting vibrant communities extends beyond architecture — it embraces a vision of harmonious living with nature. In properties like Optima Verdana®, Optima Kierland Apartments® and Optima Sonoran Village®, we’ve taken this commitment to new heights — quite literally, with green roofs elements that redefine modern living.

Amidst the greenery, residents find not only a physical haven but a sanctuary for the mind year-round. The lush landscapes stimulate cognitive skills, and echoes the enriching effects of art, where the subjective nature of greenery allows residents to explore their creativity and free thinking.

In the spirit of art therapy, our green roof communities become a refuge for stress reduction. The calming influence from a communal herb garden or native flowers and trees, provides a mental retreat, minimizing worries amid life’s challenges. It’s an oasis that mirrors the positive impact of art in promoting relaxation and inspiration.

Living with greenery encourages residents to delve into their own emotional landscapes. The transformative experience of nature’s presence becomes a sensorial, emotional, and sometimes even spiritual journey. Here, Optima’s commitment to well-being extends beyond physical spaces to nourish the soul.

Optima’s green roofs don’t just enhance the lives of residents; they also embody our commitment to environmental stewardship. By providing insulation and mitigating the urban heat effect, these green roofs contribute to energy efficiency, aligning seamlessly with our dedication to sustainable design and living. They also play a crucial role in stormwater management by absorbing and retaining rainwater, reducing runoff and minimizing flood risks.

Green roofs actively improve air quality by capturing pollutants, offering a breath of fresh air in urban environments. Beyond architectural features, they become habitats for wildlife, enhancing local biodiversity and promoting a holistic approach to community development.

In the heart of Optima’s green roof communities, residents experience a dual benefit: enhanced well-being and a commitment to sustainability. The greenery surrounding our residents tells a tale of cognitive enrichment, stress reduction, emotional healing, and environmental stewardship. As we invite nature into our designs, we reaffirm our dedication to access to greenery and sustainable living.