At Optima®, we’re passionate about design and architecture, not just as forms of artistic expression but as vital elements that contribute to the vibrancy of communities. Across the places where we build, our “forever modern” design philosophy enhances our neighborhoods with unique character, playing a critical role in enhancing the architectural mix, creating a rich tapestry for people to enjoy today…and tomorrow.

A Melting Pot of Architectural Styles

Architecture is like a visual language, telling the story of a place through its buildings. From the ornate flourishes of Art Deco to the sleek lines of Modernism, each style reflects the cultural, historical, and technological zeitgeist of its era. When these different styles coexist in a community, they create a dynamic and visually engaging environment.

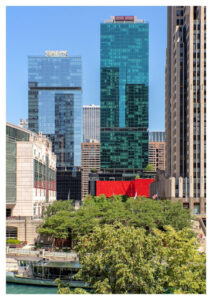

Take, for instance, a walk through a city where every corner reveals a different architectural era. The Gothic revival church with its pointed arches and elaborate stonework stands in contrast to the glass and steel of a contemporary skyscraper. This juxtaposition isn’t just about the old meeting the new; it’s a dialogue between different times and ideas, a landscape that tells the story of change and continuity.

Optima’s “Forever Modern” Contribution

At Optima, our approach is grounded in the belief that modernism isn’t a static style but an evolving language that responds to current trends, technologies, and lifestyles. By integrating the latest materials and design innovations, our buildings add a layer of contemporary elegance to the architectural conversation within communities.

Our designs, characterized by clean lines, open spaces, and a harmonious blend with the surrounding environment, offer a fresh perspective that complements the existing architectural diversity. For example, the sleek silhouette of an Optima building can highlight the ornate details of a neighboring Victorian building in downtown Wilmette, making both styles stand out.

Creating Dynamic and Interesting Communities

The beauty of diverse architectural styles lies in their ability to create vibrant, interesting, and dynamic communities. This diversity is partly visual, but it also reflects the varied experiences, histories, and values of the people who inhabit these spaces. It fosters a sense of place, where residents and visitors can feel a connection to both the past and the future.

Our commitment to modern design at Optima doesn’t exist in isolation. It’s part of a broader architectural narrative, where different styles coalesce to create a community that’s dynamic, visually engaging, and rich with stories. As architects and designers, we relish the opportunity to contribute to these narratives, because it’s in these spaces that communities truly come alive, pulsating with energy and beauty.