Today, Optima® is delighted to highlight both the exceptional career of Alison Smithson (1928-1993) and the influential partnership with Peter Smithson (1923-2003), her husband and lifelong collaborator. As visionary British architects, they jointly shaped the modernist architectural movement with their pioneering New Brutalist approach, drawing inspiration from the works of Mies Van der Rohe and Le Corbrusier. Their collaborative efforts have left a lasting legacy in the field, inspiring future generations of architects, both men and women.

Alison Smithson was born in Sheffield, England, and pursued architecture at the King’s College, Durham in Newcastle (later the Newcastle University School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape), then University of Durham, between 1944 and 1949. It was during her studies that she met Peter Smithson. United by their passion for architecture, Alison and Peter shared a desire to challenge the conventional norms of their time.

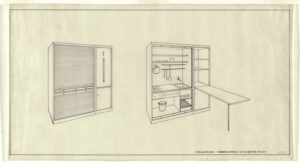

The Smithsons’ professional partnership was defined by groundbreaking projects that had significant impact on the modernist architectural movement. One of their early works, the Hunstanton School in Norfolk, exemplified the New Brutalist movement with its minimalist design and exposed structural elements. Other iconic projects include the Economist Building in London, the Robin Hood Gardens housing complex, and their own home, the Smithson House, in Wiltshire.

Alison and Peter Smithson were known for pushing the boundaries of modernist design and reimagining architectural norms. They sought to create buildings that were functional and also contextually sensitive and responsive to the needs of their occupants. By blending elements of Brutalism, modernism, and regionalism in their designs, the Smithsons carved out a unique architectural identity. They played a crucial role in the formation of Team 10, a group of designers who aimed to redefine architectural discourse, moving away from the rigid functionalism of the International Style.

The Smithsons’ innovative designs and unwavering commitment to challenging conventions have left an indelible mark on architectural history. As a woman practitioner, Alison Smithson paved her own way, while Peter Smithson’s steadfast support and collaboration underscored the importance of teamwork and partnership in the profession.

At Optima®, we take immense pride in honoring the work of Alison and Peter Smithson. Their unique partnership, innovative approach to design, and significant influence on architectural movements have contributed greatly to the field. By celebrating their collaboration, we aim to inspire future generations of architects to embrace diverse perspectives and partnerships in the pursuit of architectural excellence.