As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re spotlighting an eco-conscious architect of the early 20th century, Lilian Rice. Inspired both by the historic Spanish Colonial design she grew up in and the organic philosophy that influenced her throughout college, Lilian Rice left an impressive mark on the architecture of Southern California. Learn more about her extraordinary life and work below:

The Life of Lilian Rice

Born on June 12, 1889, Rice grew up in National City, California, just south of San Diego and only 10 miles north of the Mexican border. Her father, Julius Rice, was a prominent educator in the state and her mother, Laura Rice, an amateur painter and designer, both empowered her to pursue her interests in education and the arts.

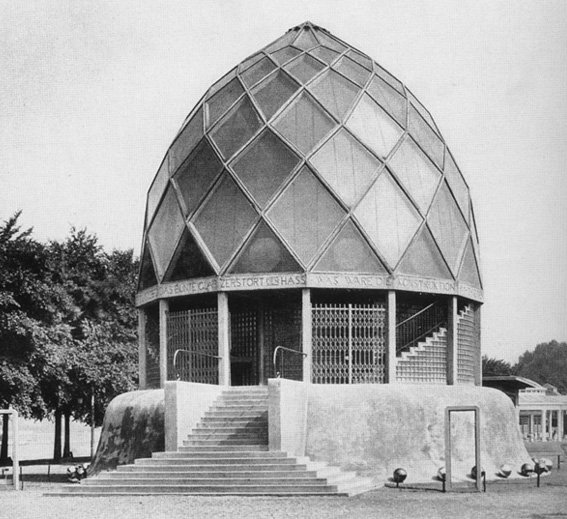

Growing up, Rice was heavily inspired and influenced by the abundant Spanish Colonial culture and architecture in the area, including the many adobe homes. In 1906, she moved to Northern California, where she started attending school at the University of California, Berkeley, where she studied architecture. Rice joined the school’s Architecture Association shortly after and quickly rose to a leadership position. At school, she also discovered her philosophy of holding a deep respect for each project’s surroundings and striving to protect their natural environments.

Following her graduation in 1910, she moved back home to National City to care for her mother and acquired a job working with San Diego architect Hazel Wood Waterman – the city’s first female architect. While working for Waterman, Rice also spent time teaching at San Diego High School, leaving her influence on many future architects, including Samuel Hamill, FAIA.

Notable Works and Achievements

In 1921 Rice’s career catapulted when Richard Requa and Herbert Jackson hired her as an associate in their architecture firm. During her first year, Requa and Jackson assigned Rice with designing a Civic Center for Rancho Santa Fe – an up-and-coming subdivision – which she eventually gained leadership over in 1923.

From then on until 1927, the majority of Rice’s work involved developments and expansions within Rancho Santa Fe. Many of the projects she designed in the subdivision are listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, including the Claude and Florence Terwilliger House and the Reginald M. and Constance Clotfelter Row House. In 1928, after she had received her architect’s license from California, Rice made the ambitious decision to open her own architecture firm.

Following the launch of her firm, Rice began working outside of Rancho Santa Fe, allowing her to step away from the Spanish Colonial style she was known for into more organic approaches. Even throughout the depression, Rice’s career excelled in the 1930s when she designed some of her most familiar works, including the Paul Ecke Ranch home, and both a boathouse and a clubhouse for the San Diego ZLAC Rowing Club in 1932.

Alongside her work, Rice has been a recipient of many architecture awards and achievements, including:

- AIA Honor Award, Chrstine Arnberg Residence, 1928

- AIA Honor Award, ZLAC Rowing Club, 1933

- AIA Honor Award, La Valenciana Apartments, 1933

- 11 buildings listed to the National Register of Historic Places

Through her diverse catalog of architecture projects, Rice filled Southern California with more than 60 unique homes. And while the Spanish Colonial Revival was prevalent at the time, Rice was one of the leading architects who helped make it widespread throughout the state, leaving a reputation little can compare.