In our journey towards a more sustainable future, architecture plays a pivotal role. At Optima®, we’re constantly exploring and embracing innovative practices that not only enhance our living spaces but also protect our planet. Among these forward-thinking approaches, non-extractive architecture stands out as a beacon of sustainable development.

So, what exactly is non-extractive architecture? It’s an approach that minimizes the environmental impact of buildings by using recycled, reclaimed, or repurposed materials. This method significantly reduces the demand for new resource extraction. While sustainable architecture is a broad term encompassing various practices, non-extractive architecture uniquely focuses on material sourcing and lifecycle.

Unlike biophilic design, which integrates natural elements to enhance human well-being, or green building, which emphasizes overall environmental responsibility, non-extractive architecture specifically targets the reduction of raw material use. It’s a crucial step towards reducing our carbon footprint and fostering a more circular economy in construction.

Recent examples of non-extractive materials include the K-Briq Construction Waste Bricks, a low-carbon alternative that is made of 90% recycled materials, Hybrit Steel, the world’s first fossil-free steel, which has the potential to reduce Sweden’s carbon emission by more than 10%, and Biotic, material research of biologically grown textiles made from resources like bacterial cellulose and dyed using natural plant and fruit waste.

Globally, several projects embody the spirit of non-extractive architecture. The Bullitt Center in Seattle, with its self-sufficient and long-lifespan design, sets a high standard. The building is home to a rainwater-to-potable water system and composting toilet system, and when developing the project, builders ensured that over 360 toxic chemicals typically used in their building materials were absent from the project.

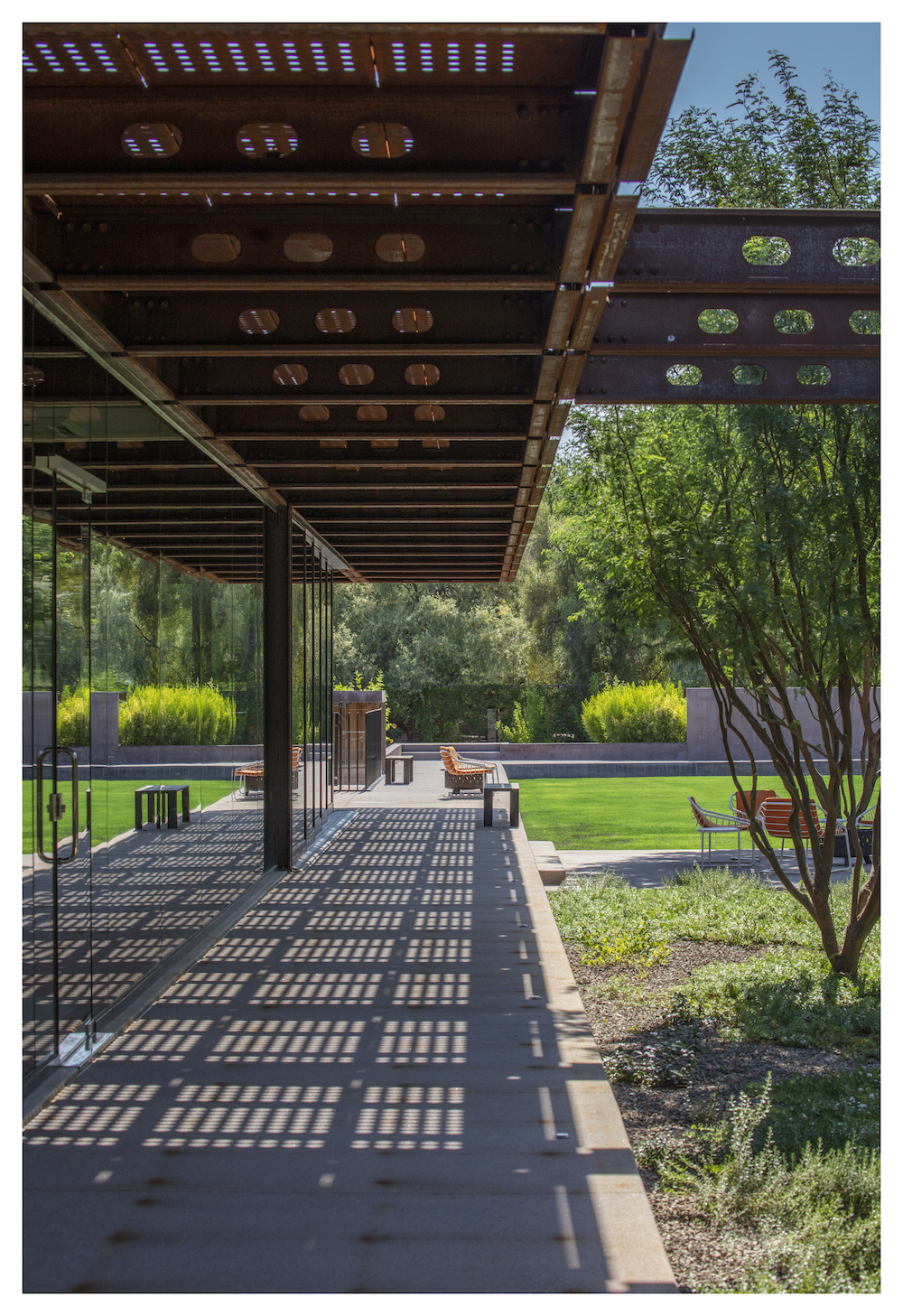

At Optima, we embrace non-extractive architecture through xeriscaping in the use of our vertical landscaping system, which features self-containing drainage and helps reduce the waste of water while contributing to a sustainable urban environment.

The world of architecture is evolving, and non-extractive design is at the forefront of this change. Our commitment to sustainable practices is unwavering, and we invite you, our community, to join us in this exciting and necessary shift towards a more sustainable world.