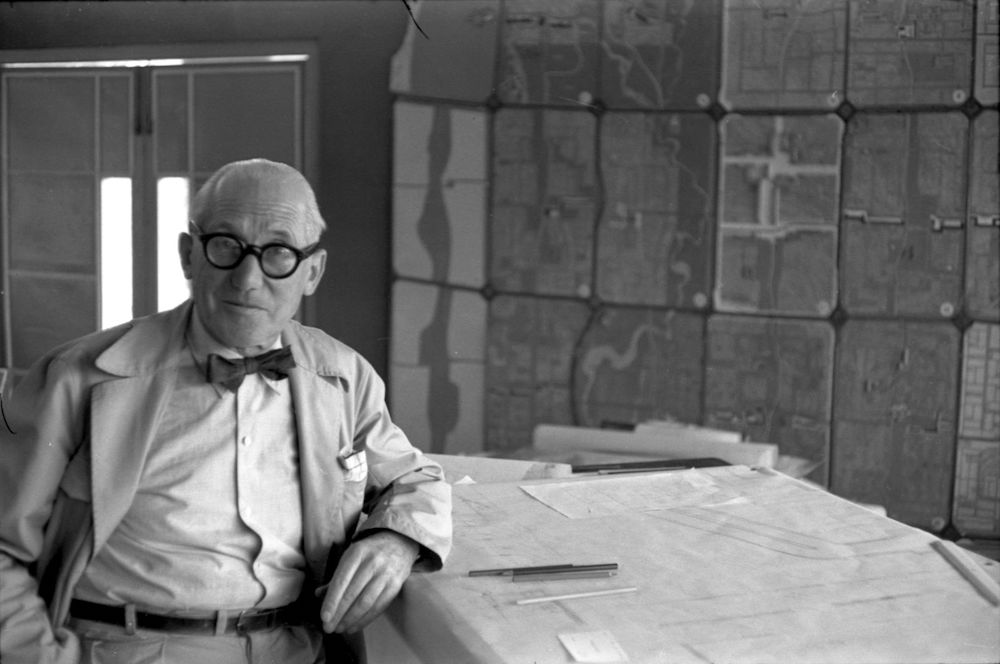

Modernism is an approach that has roots going all the way back to the 1920s. Modernist architecture was pioneered by the inventive and contentious Le Corbusier, a Swiss-French architect, urban planner, painter and furniture designer. To better understand Modernism, we’re diving deep into his life, and highly controversial work.

A Controversial Figure

Born Charles-Eduoard Jeanneret-Gris, architect Le Corbusier built chiefly with steel and reinforced concrete, paring design down to its simplest, elemental geometry and form. He developed his famous theory of modern form and minimalist materials when envisioning affordable, prefabricated housing to help rebuild communities after World War I. His vision for prefabrication was only the tip of a strong, nearly utopian, approach to urban planning and architecture.

His architectural philosophy was groundbreaking and completely contrary to the dominant narrative of the 1920s. Once he established his ideas, he shared them by publishing the seminal L’Espirit Nouveau (1920), where he revealed his famous “five points of architecture.” Three years later, he published Vers une architecture (Towards a New Architecture) (1923), in which he espoused a new, modern architecture informed by applying principles of cars, planes and ships to buildings. Le Corbusier embraced the conflict that arose to his ideas head-on, making bold declarations such as “a house is a machine for living in” and “a curved street is a donkey track; a straight street, a road for men.”

Form, Function, Furniture

Le Corbusier also designed furniture, his approach following suit to his approach to architecture. His furniture, co-designed with Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand, utilized tubular steel that projected a new rationalist aesthetic. Le Corbusier broke down furniture into three types: type-needs, type-furniture and human-limb objects. His rational approach was not without romanticism, as he said, “Certainly, works of art are tools, beautiful tools. And long live the good taste manifested by choice, subtlety, proportion and harmony.”

At Optima, we employ Le Corbusier furniture in our communities, like those in each of the three building lobbies at Optima Old Orchard Woods in Skokie. The furniture functions just as the artist would’ve wanted — as bold, artistic statement pieces, and as functional, rational furniture.