As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re spotlighting someone who accomplished many firsts in the architectural world, Beverly Loraine Greene. Greene’s drive helped to catapult her into the Chicago and New York City architectural scenes, where she would later revolutionize the lives of many. Learn more about her extraordinary life and work below:

The Life of Beverly Loraine Greene

Greene was born on October 4, 1915, in Chicago. Her family was part of the Great Migration of the early 20th century that transformed Chicago’s South Side into a vibrant community. After spending her childhood in Chicago, Greene moved to Champaign, Illinois to study at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign where she studied architectural engineering.

At school, Greene participated in the drama club and the American Society of Civil Engineers, where she was the only Black and only women member. She received her bachelor’s degree in 1936, the first Black woman to do so, and decided to stay an additional year to complete a master’s degree in city planning and housing.

Following the completion of her master’s degree in 1937, Greene moved back to Chicago, where she was hired by the city’s Housing Authority. In Chicago, she supported local theaters by painting and designing sets and costumes and began establishing contacts with notable Black architects of the time, which would lead to some of her first major projects.

Notable Work and Achievements

Greene’s first official architectural job began at Kenneth O’Neal’s architecture office – the first Black-owned architecture firm in Chicago’s Loop neighborhood. The same year she returned to Chicago, Green and a group of 20 others organized by architect Paul R. Williams developed preliminary architecture plans for a public housing project on Chicago’s South Side. After years of struggle, the Chicago Housing Authority acquired the site for the project named the Ida B. Wells Housing Project, honoring the anti-lynching activitst and journalist who shared the same name.

Because she was working for the Chicago Housing Authority, Greene spent much of her time drafting and designing the Ida B. Wells housing project, built from 1939 to 1941. The project included 1662 units and was built to house Black families in Bronzeville. The need for housing was so great that more than 17,000 individuals applied to live in the Wells project after its completion.

In 1942, Greene registered for her architecture license in Illinois and became the first Black woman to be licensed in the state and the country. In 1944, Greene left Chicago to work in New York City as an architect with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Greene worked at Met Life for only two days before leaving to become a full-time student at Columbia University, where she completed her master’s degree in architecture in 1945.

Greene spent the next few years in New York City working for architects Isadore Rosefield, Edwards Durell Stone and Marcel Breuer. Much of the work Greene completed under Rosefield involved hospital design. With Stone, she helped design the University of Arkansas’ new theater in 1949 and part of Sarah Lawrence College’s Art Complex in Bronxville, New York, in 1952.

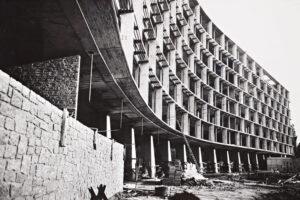

While working with Breuer, Greene helped complete two separate renovation projects in New York City. She also assisted Breuer in his designs for the UNESCO United Nations Headquarters in Paris and various University Heights Campus buildings of New York University.

Greene was a spearhead in her field, being the first Black woman to accomplish many of her achievements. Even after facing every hardship she faced in her career and life, she found work in some of the country’s most acclaimed architecture firms and was a champion for the countless Black women who followed her.