We’re always moved by stories of lost-and-found in the world of great modernist architecture, and that’s just what we discovered in a recent article by Joseph Giovannini in The New York Times about a French Modern Masterpiece brought back to life by Dominique Perrault and Gaëlle Lauriot-Prévost, the architects leading the charge for master planning the 2024 Olympics in Paris.

Giovannini observes that for many architects, time is measured in the projects they undertake, and that every new project is an opportunity to create something meaningful and lasting. And when Dominique Perrault and Gaëlle Lauriot-Prévost — partners in life and in the firm of Dominique Perrault Architecture went in search of a weekend country house outside of Paris, they were looking to feed their desire to enjoy both the city and nature. As it turns out, they were also looking for a project that would leave a lasting mark on the world.

For years, Perrault Architecture honed their appetite for monumental projects, including the design of the National Library of France in Paris in 1989 when Perrault was only 36. In looking for a country home, on the other hand, Perrault and Lauriot-Prévost were motivated by the desire for something personal, something that would reflect their own tastes and sensibilities rather than building for others.

They considered a host of options in their search for the right property, including repurposing a former factory. Nothing seemed quite right until a real-estate agent specializing in architect-built homes introduced the couple to a Modern masterpiece that had been largely forgotten — the Villa Weil, designed and built by Jean Dubuisson, a third-generation Parisian architect who came out of the École des Beaux-Arts to design Modernist housing blocks that helped build the infrastructure of France as it emerged from the wreckage of World War II. Villa Weil, situated in a protected forest near the medieval town of Senlis, north of Paris, was commissioned by the real estate developer André Weil and completed in 1968.

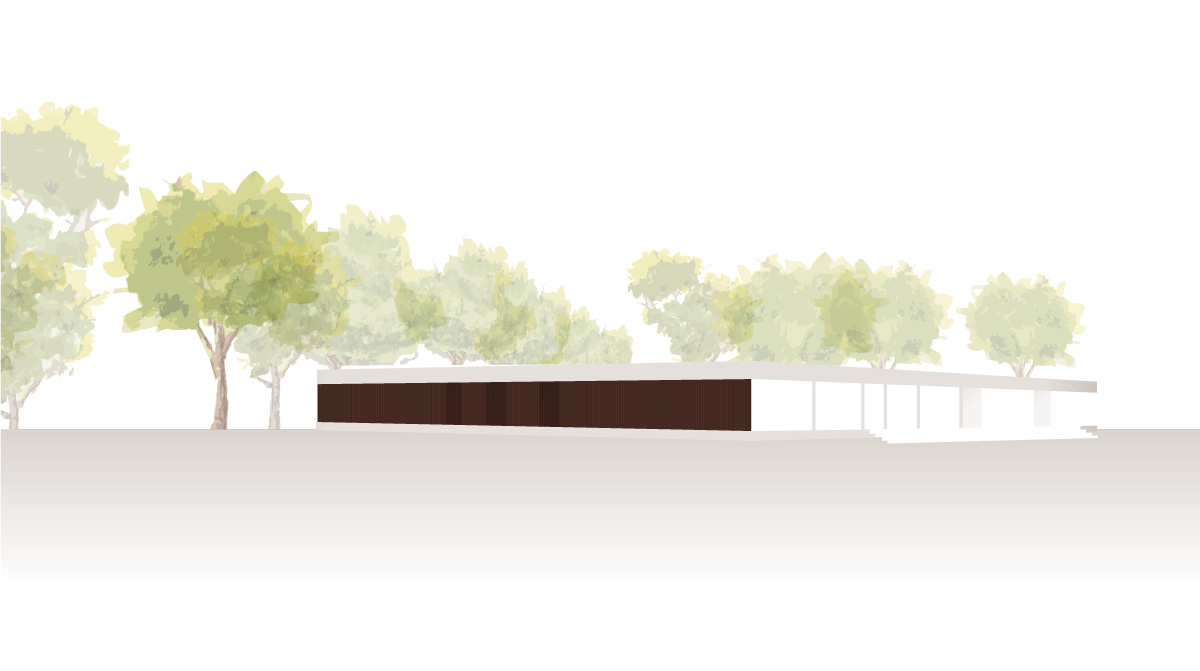

Perrault and Lauriot-Prévost saw something special in the house, described by Giovanni as “a straight line of a building streaking across the landscape.” He writes, “Inside and out, the clean white planes, crisp machined corners and squared geometries are derived from International Style Modernism and recast into a new synthesis….The abstract lines and planes, like picture frames, bracket outdoor terraces that are landscaped like the Zen gardens Dubuisson had seen in Japan. Huge sliding glass doors recall the indoor-outdoor relationship of mid century Modernist California houses, by then well known in Europe.”

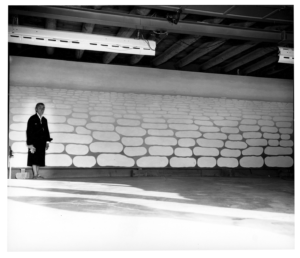

But the home wasn’t without its issues, since it had languished for years without proper attention. They restored the house with exquisite attention to its original design and materials. Today, Perrault and Lauriot-Prévost enjoy the long-forgotten estate with their two dogs, furnished with original mid-century Modernist furniture sourced online. As Giovanni relates, the couple remains dedicated to “expanding the property to its fullest potential — the basement and barn are being turned into exhibition spaces for a variety of shows and a home for their collection of models and drawings.” At the same time, the vision of the owners is to design and build flats that will host resident artists, architects, and researchers as part of a study center that will expand the life of the semi-private villa into a campus for a larger architecture and design community.