As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re spotlighting a master of technical design and someone who played a critical role in advancing the field for women, Sophia Hayden Bennett. While her builds were limited, Hayden’s talent and enthusiasm led her to achievements few people had reached at the time. Learn more about her impressive life and accomplishments below:

The Life of Sophia Bennett

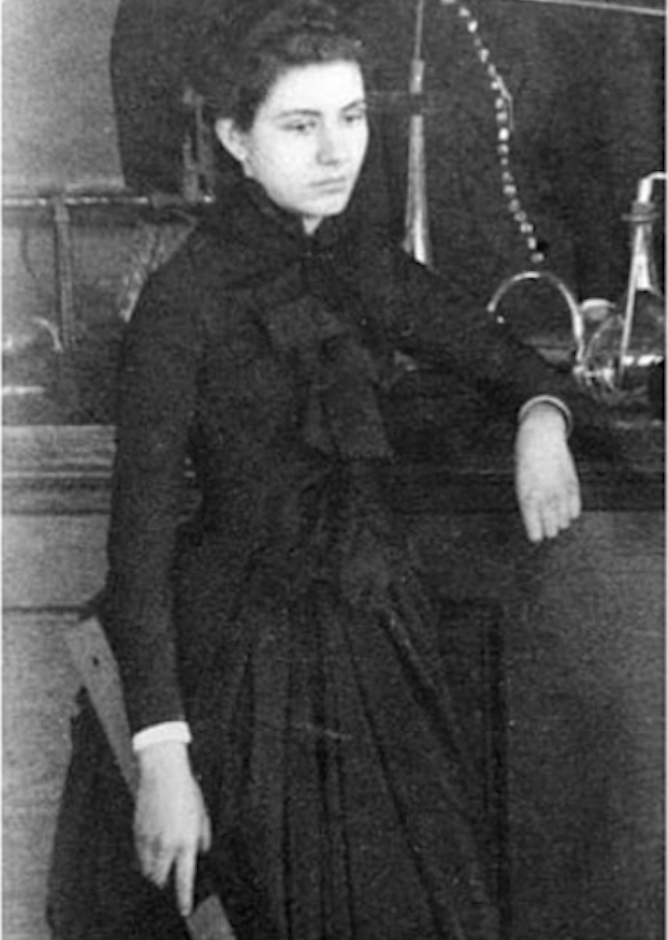

Sophia Hayden Bennett was born in Santiago, Chile, on October 17, 1868. Hayden’s mother was of Peruvian descent, while her father was originally from the northeast United States. She spent her childhood in Chile but later moved to Boston to live with her grandparents and attend high school. In high school, she found her love for architecture, which emboldened her to apply to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1886.

Hayden was the first woman admitted to the MIT bachelor’s program in architecture and one of only a few women attending the school at the time. She became the first woman to graduate with a degree in the program four years later, in 1890. Throughout her time at MIT, Hayden’s classes ranged from niche drawing topics to construction and business courses, and she exuberantly mastered each subject, steering her to her final thesis, a design for a Museum of Fine Arts.

Notable Works and Achievements

Following her graduation from MIT, Hayden continued her passion for technical drawing as a teacher of mechanical drafting at a school in Boston. However, in February 1891, the World’s Columbian Exposition announced their competition for a design of the Woman’s Building, an exhibition hall for the 1893 Chicago exposition, and Hayden saw an opportunity she couldn’t pass up.

Entries for the contest were limited to only designs made by women, and advertisements specified that each entrant must have professional architecture training. In the end, only twelve total entrants submitted designs, all under the age of twenty-five. Hayden’s design was eventually chosen as the winning design by a jury, which included Daniel Burnham. Along with being appointed as the building’s architect, she received a $1,000 prize.

The winning design featured an Italian Renaissance classicism style, similar to the characteristics Hayden employed in her MIT thesis. The rectangular, two-story building utilized a wood structure and featured a central portico bordered by two symmetrical wings. At its interior, a central rotunda acted as the heart of the building, with rooms featuring exhibits of works by women across the world surrounding it.

Following the construction of the building, both Hayden and her design received public acclaim. Even with its praise, the commission – which was Hayden’s first – ended up being her last. However, she continued lending her design and drawing skills elsewhere, none of which became constructed.

While Hayden’s physical contributions to the architectural world were limited, her expertise in technical drawing and passion for expanding opportunities for women in her field helped shape a storied legacy of her own.