In “The Other Art History: The Forgotten Women of Bauhaus,” an in-depth piece that was published on July 13, 2018 on Artspace by Jillian Billard, we have the opportunity to understand the enormous impact a group of women visionaries had in shaping the Bauhaus.

We learn from Billard that the Bauhaus was dedicated to “interdisciplinary innovation” by combining design and craft through a new model of fostering community as the basis for learning instead of traditional teacher-student interactions. And with this new model as a defining principle, the Bauhaus community was ripe for welcoming and supporting women artists.

As Billard explains, Walter Gropius, who founded the Bauhaus School of Design in Weimar, Germany in 1919, stipulated that the school would be open to “any person of good repute, regardless of age or sex.” So while women were allowed to study at the school, they were directed into practices commonly regarded as “women’s work” –– textiles and weaving — while their male counterparts were encouraged to be architects, sculptors, and painters.

Billard reminds us that the artists most closely associated with the Bauhaus were men, including Josef Albers, Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. At the same time, history has treated the women in the movement as the counterparts of these great artists. In the past ten years, as many have revisited the Bauhaus participants in a more accurate art historical context, we have had the opportunity to celebrate the incredible women artists and the contributions they made.

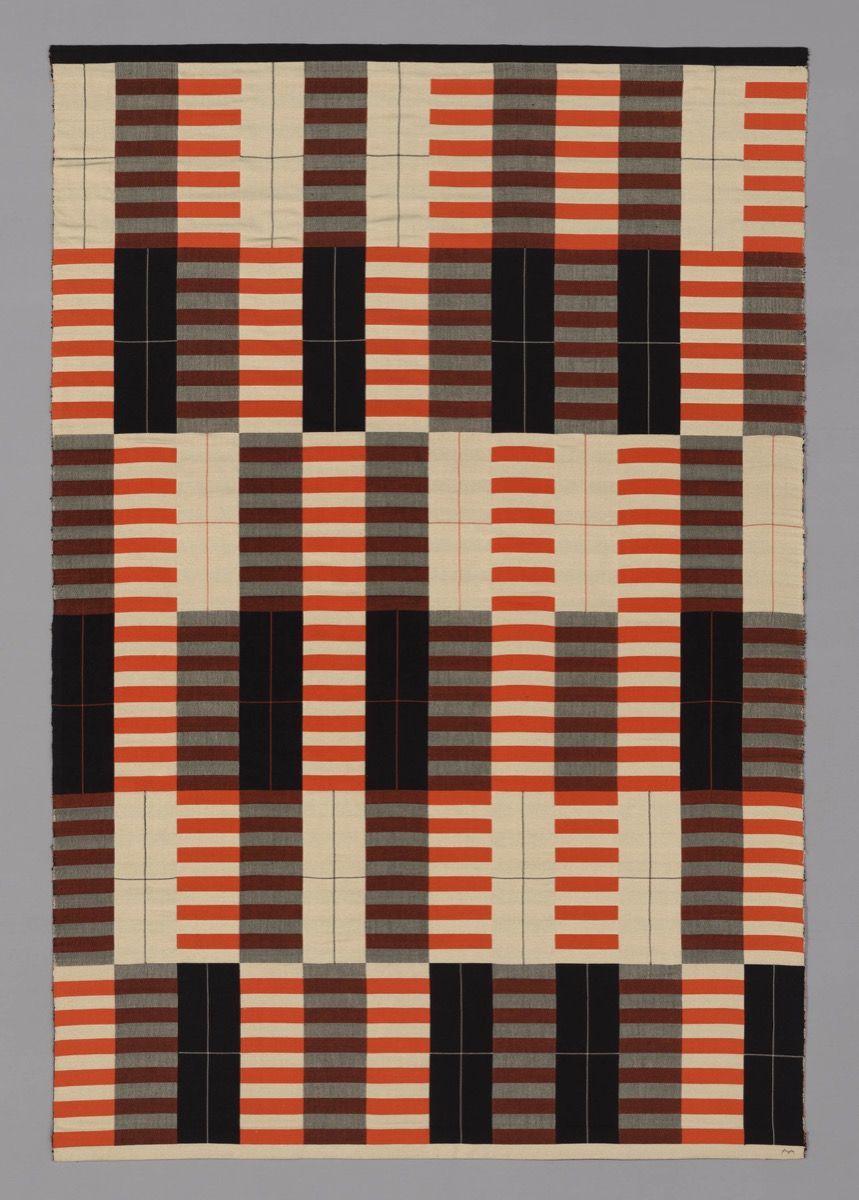

In “The Women of the Bauhaus,” an extensive thesis presented by Corinne Julius in Blueprint on September 3, 2019, we learn of the rise to prominence of Gunta Stölzl, only one of six students certified as a Master weaver. As head of the department from 1929 to 1931, she ushered in the transition from individual pictorial weaving to modern industrial designs, while also implementing the study of mathematics. Her bold artistic experiments include creating the mercerised cotton and Eisengarn fabric for Breuer’s tubular-steel chairs while leading joint projects with the Polytex Textile Company.

Julius describes Marianne Brandt as a brilliant metalwork artist who joined the Bauhaus as a workshop assistant and eventually took over as acting director in 1928 from László Moholy-Nagy. As both artist and administrator, Brandt helped solidify the role of industrial design

Wera Meyer-Waldeck entered the Bauhaus in 1927, studying with Marcel Breuer in the carpentry workshop making furniture. Over the next several years, she studied in the construction and architecture departments, and went on to establish a distinguished career with a focus on sustainable housing.

And the list goes on. As we shared in Female Weavers and the Bauhaus, virtually every aspect of the Bauhaus and its artistic practices has been informed by a group of women with talent, vision and unapologetic courage. They, along with their male counterparts, continue to inspire the timelessness of Modernist thinking-and-doing. And in every part of our holistic design thinking at Optima, we celebrate their contributions.

For further reading on 45 luminary women of the Bauhaus, Bauhaus Women: A Global Perspective, written by Elizabeth Otto and Patrick Rössler and published in 2019 by Bloomsbury Publishing, is an excellent resource, along with A Tribute to Pioneering Women Artists (Taschen, 2019), written by Patrick Rössler.