Women continue to make giant strides in architecture today, contributing to some of the most celebrated designs in the world. Historically however, many trailblazing women and their designs became overlooked and overshadowed. Today, we’re spotlighting a pioneer of tropical-modern design in Southern Asia, Minnette de Silva.

Minnette de Silva’s Life & Career

De Silva was born on February 1, 1918, in Kandy, Ceylon – present-day Sri Lanka. Her father, George E. de Silva, was the President of the Ceylon’s National Congress and was a well-known politician. Her mother, Agnes Nell, was an activist who pushed for universal suffrage throughout the country. As a child, de Silva attended school overseas in England, spending much of her youth away from her family. However, when home, her family would frequently visit the architecture of ancient Sri Lankan cultures, influencing her profoundly.

Because she wasn’t able to study architecture in Sri Lanka, de Silva convinced her father to allow her to attend Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art in Mumbai, India. Coming into the country with no previous architecture experience forced de Silva to learn the trade through apprenticeship and additional schooling at the Architecture Academy Mumbai before she was able to attend Sir J.J. School of Art.

After being expelled from the academy in 1942, de Silva started working under emigre architect Otto Königsberger designing prefabricated housing in Bihar, India. And not long after, through connections back home, she was admitted to the Royal Institute of British Architects, where she built relationships with some of the world’s most inspiring architects.

After Sri Lanka’s independence in 1948, de Silva’s father insisted she come home and contribute to the growth of her home country. So, de Silva moved back into her parents’ house with no money to her name and opened her studio – one of only two studios in the world named after the woman they were owned by at the time.

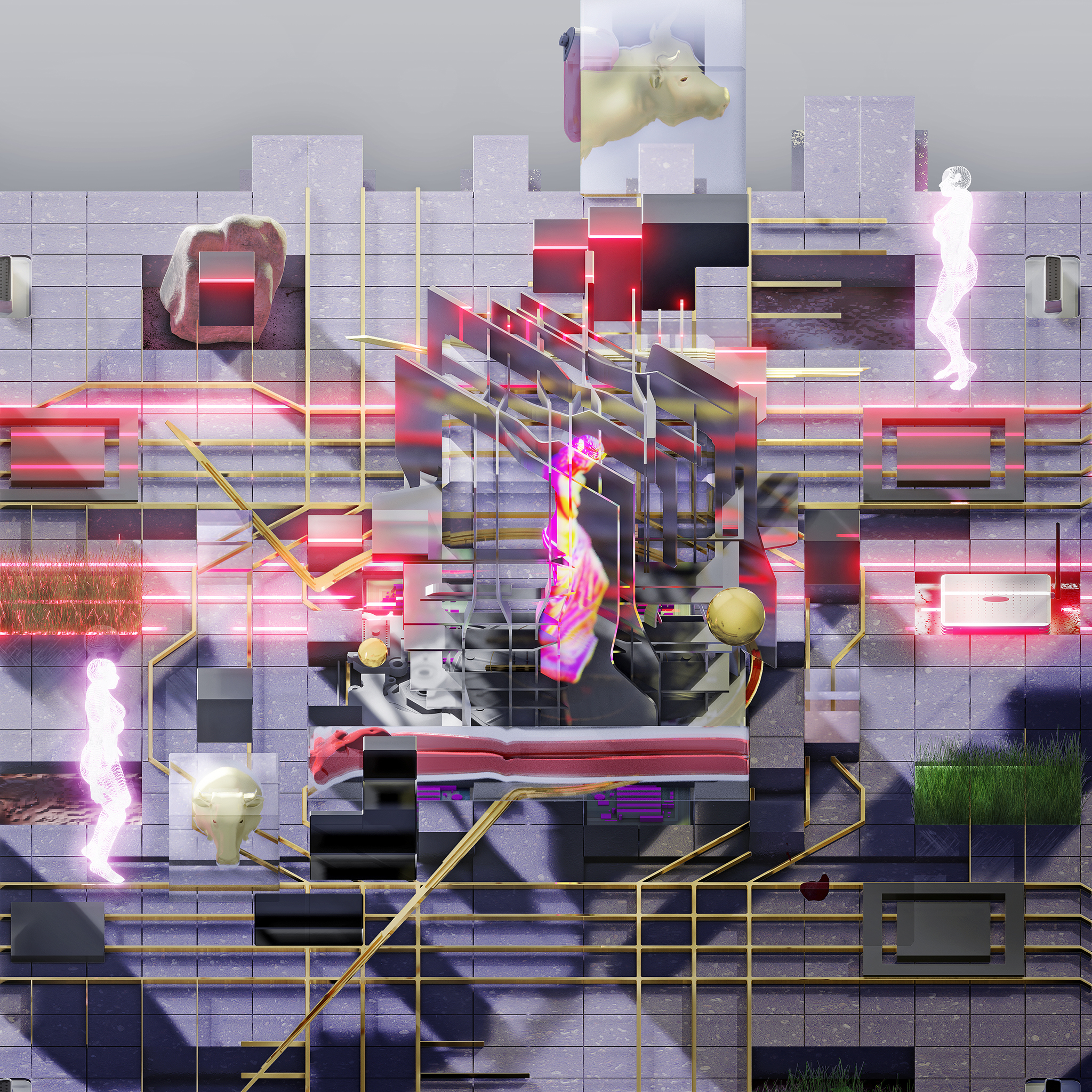

While back in Sri Lanka, de Silva developed her unique architecture style, influenced by a mixture of the traditional architecture she grew up with and the modern builds she was exposed to outside of her home country. In hopes of becoming exposed herself, de Silva began designing everything she could from small cottages to luxurious villas.

Notable Works & Achievements

Her first build was the Karunaratne House, built for family friends from 1949 to 1950. At the time of completion, the house was the first building in the country completed by a woman and received much attention and controversy. The house was an exhibition of Silva’s design philosophy. Featuring woven Dumbara mats used as interior door paneling, clay tiles fired with ancient patterns and a custom mural in the living room designed by local artist George Keyt.

De Silva’s next build, Pieris House, was another commissioned home for family friends, this time in the country’s capital, Columbo. The open plan echoed traditional Sri Lankan architecture with a courtyard incorporated into its living room, which became a hallmark of de Silva’s designs. The house also featured one-of-a-kind patterned tiles and railings lacquered in gold leaf prints.

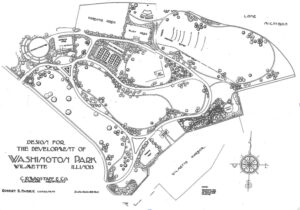

One of her later but most acclaimed builds came in 1958 for Kandy’s Public Housing Project. The ambitious project had de Silva conduct extensive research and interviews with various house seekers in the city to uncover each of their unique lifestyles. She then used the information she received to curate and design custom housing types for each family – some families even assisting her throughout the process.

While today this approach to design is celebrated, at the time, de Silva’s prospect was suspect and left unsupported. However, she knew the ultimate success would lay in whether the homeowners felt their environments were accessible to their lifestyles. The project eventually became a huge success and quickly became a model used throughout the country, encouraging the boom of strong mixed cultural communities in Sri Lanka.

De Silva was awarded the Gold Medal by the Sri Lanka Institute of Architecture in 1996. She championed a new, inspired vision in Sri Lanka, mixing modernism with the traditional design elements that excited her growing up. Even though few of her buildings survive today, her legacy as a pioneer of tropical-modernism remains.