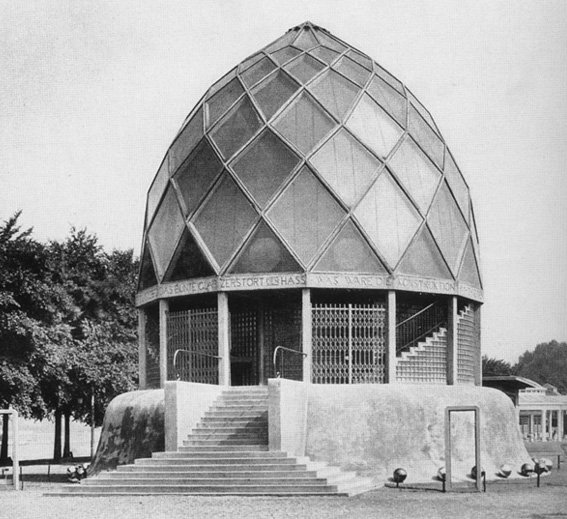

Chicago has earned its place on the architectural map thanks to the countless architects who helped fill the city with unique designs. Not to be outdone, the Chicago suburb and home to Optima Verdana, Wilmette, also boasts a myriad of architectural wonders itself, from houses designed by Frank Lloyd Wright to a Prairie-style ‘L’ station still in use. Today, we’re taking a closer look at the architectural history behind Wilmette’s iconic Baháʼí House of Worship.

Plans to construct a Baháʼí temple in the United States began in 1903. At the time, only one other temple existed throughout the rest of the world in Turkmenistan. Baháʼí’s presence in and around Chicago made it the perfect city to build in, but leaders in the religion wanted to build in a quaint community outside of the city and eventually, they decided on Wilmette to harbor the temple.

In 1907, individual Baháʼí contributors purchased two lots alongside Lake Michigan. Groundbreaking on the nearly 7-acre site began in 1912, but construction on the building didn’t start until eight years later, in 1920. The community chose Canadian architect Louis Bourgeois – a collaborator of Louis Sullivan – to design the temple.

Bourgeois’ design drew inspiration from Baháʼís’ belief of unity and was chosen due to its diverse inclusion of architectural styles. The most prominent architectural styles include Neoclassic, Gothic, Renaissance, Romanesque and Islamic arabesque. The temple’s superstructure was completed in 1931, and construction on the building’s entire exteriors finished in 1943. However, the interior had yet to be designed.

Designers had a difficult time choosing what material to use throughout the design, debating between granite, limestone, terra cotta and aluminum before deciding on concrete made of cement, quartz and other natural stone. Many intricate details are carved into the concrete drape across the exterior facade. Along with its lush gardens and fountains the temple’s most brilliant feature is its 72-foot-wide dome. The temple features nine dome sections and nine interior alcoves, symbolizing completion.

More than 3,500 people attended the dedication of the temple in 1953 following the completion of its construction. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 and is continuously voted one of the most must-see places in the country.

Today, Wilmette’s Baháʼí’ House of Worship is the oldest standing temple of Baháʼí and the only in North America. To learn more about the architectural wonder and visit it yourself, head to the website here.