A hallmark of Optima properties is our integration of the built environment with the natural. Oftentimes, we employ terraces—level platforms incorporated into buildings that allow for plantlife to thrive—that allow our buildings, and their residents, to live in harmony with the surrounding landscape. The usage of terraces is one that dates back for over 12,000 years, evolving over the millennium to be the sophisticated components of urban architecture that they are today.

Terraces of Ancient Times

The word terrace is derived from terra, the Latin word for earth. The technique has been in use for over 12,000 years, first utilized as an ancient farming method in hilly regions. Agricultural terracing involved cutting the land into a series of successively receding flat platforms, much like steps, to allow for more effective farming, by decreasing erosion and surface runoff and increasing the effectiveness of irrigation.

In 9800 BC, ancient civilizations realized that they could adapt this technique to buildings, and they began to add terraces to their homes and other domestic structures. This first usage was seen across the globe, from the Middle East to the Pacific Islands. The most famous interpretation is undeniably King Nebuchadnezzar’s Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Although no actual proof of its existence has been found, depictions show an ascending series of tiered gardens abundant with plantlife, complete even with a waterfall.

Thousands of years later, from 3000 BC – 600 BC, Mesopotamians grew gardens atop ziggurats, terraced religious temples that allowed for religious spaces to become placed ever higher. The structures were placed upon many layered platforms, and it’s believed that ziggurats were what inspired the Biblical parable The Tower of Babel.

Terraces continued to be integrated into homes. Around 1500 AD, Venice adopted terrace design to the tops of their homes, called altanas. Altanas were private, slat-floored roofs. They started out as a place to hang laundry out to dry, but continue to be used today as social spaces.

Terraces in the Modern Age

Following the progression of altanas as a place to socialize, people began more and more to use the terrace as a location to congregate in privacy. Private rooftop and per-unit terraces became luxury amenities in the 1920s, when building height began to increase due to the adoption of the elevator. At that time, terraces become a status of wealth, allowing for privacy, fresh air and separation from the increasing bustle of life on city-level.

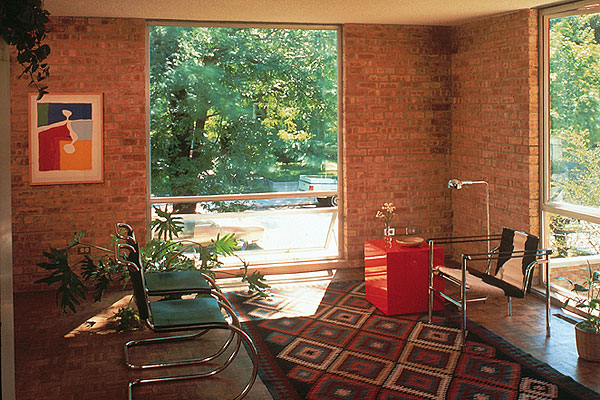

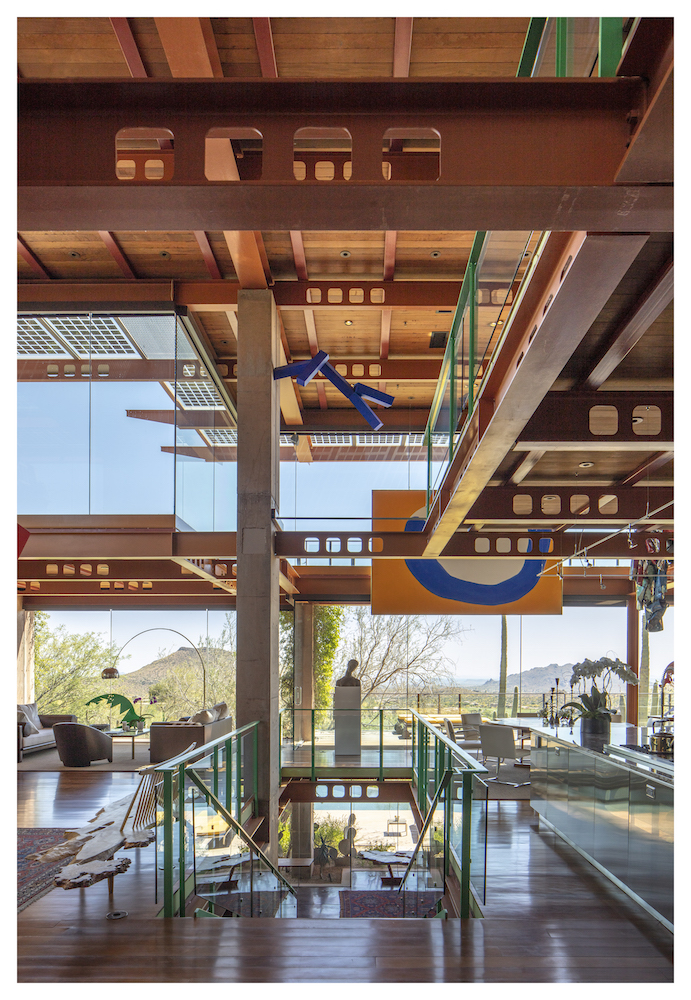

Today, the use of terraces continues to flourish, finding increased purpose and urgency in response to population growth and a changing environmental climate. They provide private places to reconvene with nature, away from the bustle of the city. Terraces also create sustainable and contributive space, by providing thermal insulation, solar shading to mitigate air pollution, increased biodiversity and enhanced quality of life.

At Optima, we incorporate terraces to create private social space, to integrate nature into our communities through our signature hanging gardens, and to contribute to our sustainability practices at many of our properties, including Optima Camelview Village, Optima Sonoran Village and Optima Kierland. Terraces at Optima serve as outdoor living space, connecting the outdoor and indoor for a seamless living experience. From agricultural beginnings, the terrace stays true to its roots, allowing us to find harmony with nature.