From Taliesin and Taliesin West to his home and studio in Chicago, Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic architectural contributions continue to remain beloved treasures of modernism. And while many of the buildings attract tourists from across the world, one home, in particular, separates itself as his most documented property, and whether you know it or not, you’ve probably seen it yourself.

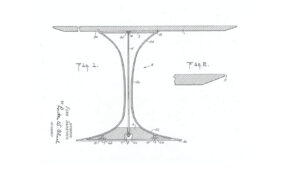

Built in 1924, the Ennis House was only the second home Wright built in California. Situated in the Los Feliz neighborhood, Wright embraced the Mayan Revival style of the time and area, utilizing 27,000 concrete molds in a block construction to create the famous house. Along with the custom textile block design, Ennis House features a tall loggia spine and grand pool on its northern terrace, one of the house’s most glamorous features.

Although the house was built as a residence for Charles and Mabel Ennis, its exotic design immediately attracted the eyes of Hollywood filmmakers. In 1933 it was used as a shooting location for the first time, but it wasn’t until 1959 that it acquired unnatural recognition for the time as the exterior facade for the B movie House on Haunted Hill. The home remained a popular destination for films for decades, showcasing its impressive interior for the 1975 film, The Day of the Locust.

However, in 1982 the home reached new levels of fame after appearing in Blade Runner. While it was only actually filmed for one exterior scene, the director was so entranced by the textile blocks that casts of them were created for sets elsewhere in the movie. The tall ceilings from the cathedral-like dining room and fireplaces were also popularly used in films thanks to their haunting nature.

Since 1933, features from the iconic house have made appearances in more than 80 films, alongside various commercials, magazine covers and music videos. The Ennis House is designated a city, state and national landmark and added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1976. It remains privately owned today, but thanks to its inspiring and timeless architectural design, it remains a desired location for anyone looking to capture the perfect shot.