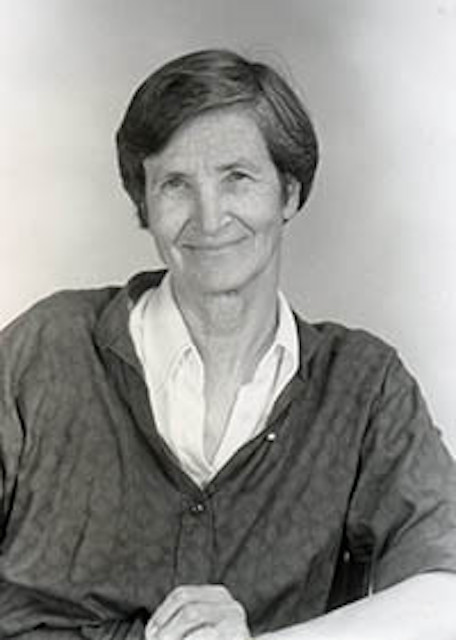

As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re spotlighting a designer who generously contributed to the refined elegance of American modernism, Natalie de Blois. As an early advocate for women in architecture, de Blois became well-known in feminist architecture circles around the world. Learn more about her incredible life and career below:

The Life of Natalie Griffin de Blois

De Blois was born on April 2, 1921, in Paterson, New Jersey. Following three generations of engineers in her family, she knew by the age of 10 that she wanted to become an architect. Supported by her father, de Blois’ interests in art and architecture flourished; thanks to him, she enrolled in a mechanical drawing course in school, which was typically limited to male students at the time.

The class not only helped de Blois evolve her drawing skills for what would become her passion, but it also introduced her to the bias she would experience throughout her career. In 1939, she visited the New York World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, further expanding her understanding and vision for modern architecture.

De Blois enrolled at Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio but soon transferred to Columbia University after they changed their architecture school’s admission policy. While at Columbia, de Blois worked for various firms drafting various presentations and projects

Notable Works and Achievements

Following her graduation in 1944, de Blois immediately received her first position at Ketchum, Gina and Sharpe, a firm she admired for their dedication to modern design. However, she left due to gender bias less than a year after starting. But, while one door closed, another opened at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), where de Blois’ talents were finally celebrated.

At SOM, de Blois contributed to seminal design proposals including the United Nations Headquarters and Lincoln Center, but it wasn’t until 1948 that she led her first project, Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati. The hotel immediately received praise for its modern, luxurious look and high-tech amenities for the time. She also contributed designs to many of the firm’s other significant projects, including Manhattan’s Lever House, completed in 1952 and the Pepsi-Cola Headquarters, finished in 1960, perhaps the most complete example of her most modernist design aesthetic.

In 1961, de Blois relocated to work for SOM’s Chicago office, where she was promoted to Associate Partner. In Chicago, she prioritized advocating for women in her field and was a founding member of Chicago Women in Architecture and was appointed to the AIA Chicago Taskforce on Women in Architecture in 1974. However, de Blois left the firm the same year and moved to Texas, where she completed her career in architecture, later becoming a professor at the University of Texas School of Architecture.

Alongside her revolutionary work, de Blois has received various design awards and achievements, including:

- Fellow, American Institute of Architects, 1974

- Edward J. Romieniec, FAIA, Award for Outstanding Educational Contributions, Texas Society of Architects, 1998

- Tallest woman-designed building in the world, 270 Park Avenue, from 1960 until 2009

Throughout her illustrious career, de Blois’ proved to be a force to be reckoned with. And, in her lifelong pursuit of gender equality, she proved that women could compete at the highest levels of the architecture profession, empowering the careers of countless women who followed her.