Strike up a conversation with any kitchen aficionado and talk will quickly turn to induction cooking. At Optima, we are bringing this state-of-the-art cooktop appliance to our communities, offering great advantages in culinary innovation, energy efficiency and design. Here’s what you need to know.

How does it work?

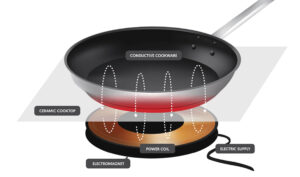

In simple terms, induction cooking uses a surface that heats by transferring currents from an electromagnetic field located below the glass surface directly to the magnetic induction cookware placed above.

While gas and electric stoves heat cookware indirectly by first heating a coil, burner, or producing a flame, induction cooking provides direct heat to the cookware which then passes the radiant energy on to the food. Instead of a heating element, magnets are used to stimulate the atoms inside your cookware and heat the pot or pan.

Because induction cooking offers direct heat to cookware, it is an incredibly efficient option that gives the user more control over the cooktop. Additionally, the heat is directly sourced, which means the temperature tends to stay much steadier than electric or gas ranges as well.

Without a separate element, an induction cooktop puts out less waste heat and no air pollution into the kitchen. Cooktops are also easy to clean, since the cooktop itself has a smooth surface and does not get very hot.

Refined design

For home chefs who opt for a clean, minimal look, induction cooktops are a great option. The subtle black glass and durable matte black detailing seamlessly blend with other appliances for a cohesive, considered kitchen design.

Why change?

Induction cooking has always been popular in Europe, because of its energy-efficiency and low environmental impact. In addition, trendsetting restaurateurs and professional chefs are induction cooking enthusiasts, as they appreciate a newfound combination of precision and practicality.

Here’s what the experts are raving about:

Speed. With induction technology, heat is transferred directly to your cookware, not to the surface of the cooktop itself. This means food heats more quickly and water boils 50% faster when compared to electric or gas cooktops.

Heat Transfer. Induction cooktops are only hot when burners are engaged — as soon as you remove a pot, the heat transfer stops. As a result, the glass surface never gets as hot as it would on a traditional radiant electric range. And for added safety, if you turn on an induction burner without a pot on it by mistake, it won’t heat up.

Temperature Control. To reduce the chances of over- or -undercooking, you can control the temperature on an induction cooktop with great precision. This includes the flexibility to turn a burner off completely, which immediately stops the transfer of heat.

Easy Cleaning. With their smooth, glass surface, induction cooktops are a breeze to clean. Spills and splatters don’t bake onto the surface, and you can easily wipe them down with a soft rag or sponge.

Gentler on the Environment. Induction cooking is far better for the climate and eliminates harmful pollutants from your home. Whereas gas stoves emit nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO), and formaldehyde (HCHO) that is both trapped in your kitchen and expelled into the environment through the ventilation system, the electromagnetic technology used in induction cooktops is pollutant-free. At the same time, induction cooking consumes less energy because of the speed and efficiency of the heating process.

The fan base is growing…

On July 1, 2022, Hannah Goldfield, food critic for The New Yorker, published a piece entitled, “Learning to Love an Induction Stove.” In the article, she describes her contempt for anything other than gas cooking, along with her recent change of heart. She recounts her adoption of an induction cooktop with humor and in terms we can all understand — of its kindness to the environment, its efficiency and its sleek design that also frees up additional counter space in her kitchen.

So whether you’re a savvy chef or an occasional cook, you’ll find new inspiration and peace of mind with a move to using an induction cooktop!