As we continue to discover Modernist treasures in and around Chicago, we came upon the work of Paul Schweikher, a visionary architect who studied, lived and worked in Chicago between 1938 and 1953. It’s a welcome surprise that Schweikher House, his home and professional studio, are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and are open for public tours.

About the Architect

Paul Schweikher graduated with an engineering degree from the University of Colorado Boulder and moved to Chicago to study at The Art Institute. In the 1930s, he began a collaboration with George Fred Keck, a visionary Modernist architect known for his design of the House of Tomorrow at the Century of Progress International Exposition. Equally impressive, Schweikher’s work was included in a major architectural exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1933, the Work of Young Architects in the Middle West. Schweikher went on to establish an architectural practice in 1934; it was in this practice that he designed some of his most celebrated commissions including the David B. Johnson House (Chicago, 1936), Emerson Settlement House (1939, Hinsdale, IL) and Louis C. Upton House (1950, Paradise Valley, AZ).

After being named chairman of the Yale School of Architecture in 1953, Schweikher became head of the Carnegie Mellon School of Architecture in 1958 and retired in Sedona AZ in 1970.

The Schweikher House

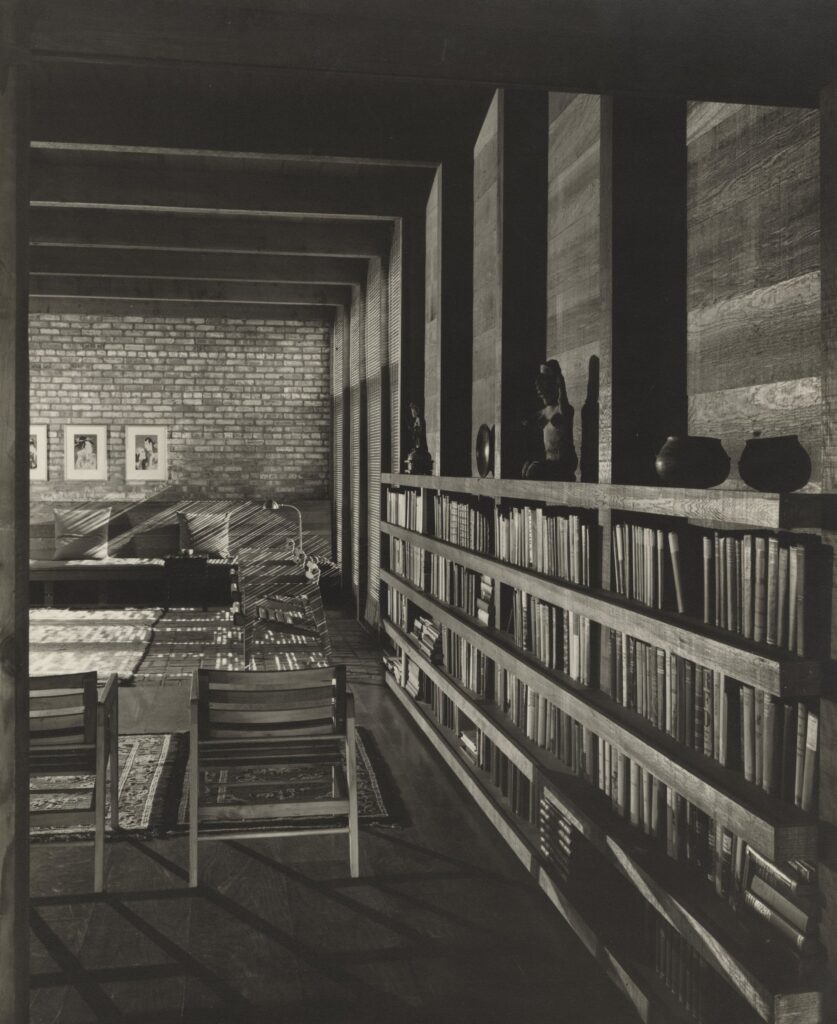

Schweikher built the house in 1937-38, after being inspired on a trip to Japan to study the country’s architecture. As both his private residence and his professional architecture studio, the building reflects a unique amalgam of Prairie, Japanese and vernacular architecture — with a strong modernist underpinning.

The one-story, T-shaped house was a complete remodel of an old barn situated on a 7-½ acre plot of farmland on the outskirts of Chicago in Roselle, IL. Schweikher chose common materials including brick, red cypress wood and glass to reflect his interests in sustainability and engineering. He designed the interior as distinct areas for sleeping, living and working, connected to allow for a constant flow of natural light and air. He built a massive fireplace in the living room to establish the house’s character, while giving the Chicago common bricks center stage. Inspired by the Japanese minimalist architecture he had seen on his travels, Schweikher included a passive solar room, exposed wood beams, built-in furniture, a soaking tub, concealed storage in the paneling in each of the rooms, and shoji screens throughout the building.

After nearly a decade of serving as the Schweikher home and studio, the house was featured in the May 1947 issue of Architectural Forum magazine. By that time, the surrounding gardens designed by Franz Lipp, one of the country’s foremost landscape architects, had matured magnificently. In 1948–50, Schweikher made a series of additions including a formal studio that cantilevers over the large back yard and connects by a breezeway to the main building.

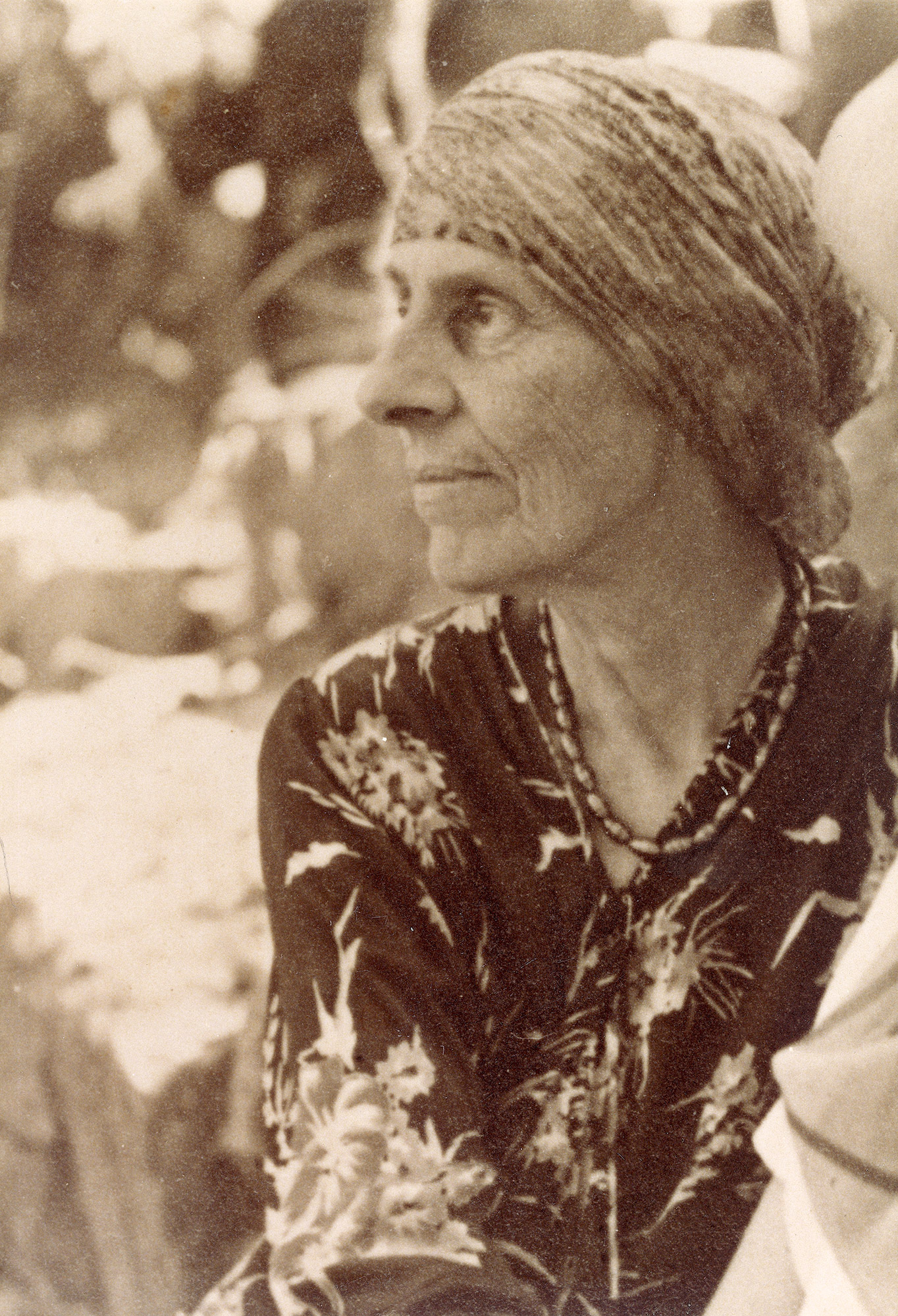

In 1953, when he took up his new position at Yale, Schweikher sold the home to Martyl and Alexander Langsdorf. Over the ensuing decades as owners and occupants, the Langsdorfs maintained the building and grounds with meticulous care, and spearheaded the effort to have it listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987. In 1999, they sold the Schweikher House to the Village of Schaumburg in 1999 so it could be preserved as a public house museum, allowing this treasure of timeless architectural value to be experienced, enjoyed and learned from by all.

Scheduling a Visit

The Schweikher House is located at 645 W Meacham Road in Schaumburg, IL. Tickets to docent-led tours can be purchased online; a reservation is required.