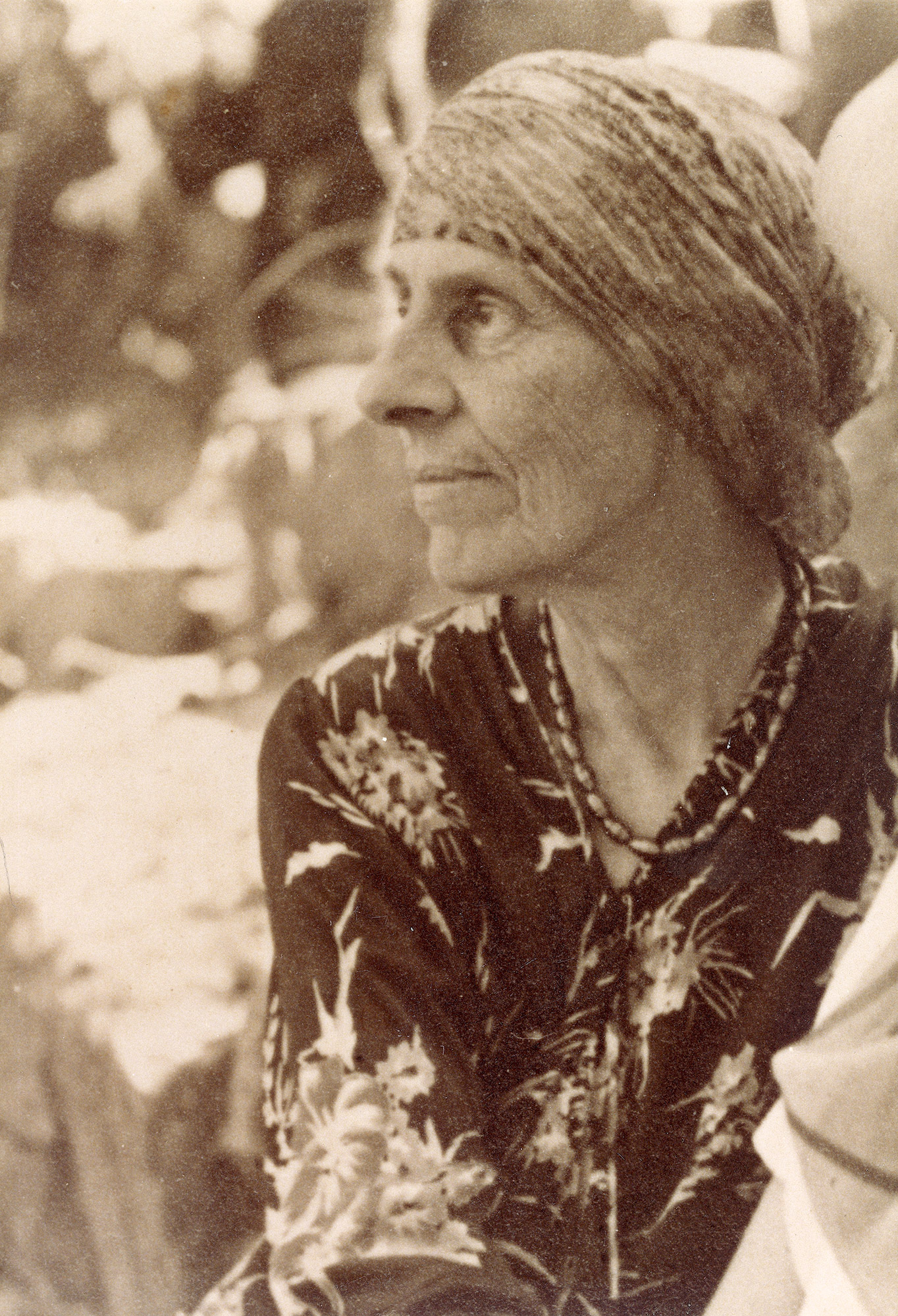

As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re spotlighting one of America’s most overlooked architects. As one of only two women in the original Prairie School, Isabel Roberts immediately became an inspiration for women architects in the early 20th century. Learn more about her riveting life and career below:

The Life of Isabel Roberts

Isabel Roberts was born on March 7, 1871, in Mexico, Missouri. Her parents were natives of the eastern coast; her father was a mechanic from Utica, New York, and her mother was from Prince Edward Island, Canada. Growing up, Roberts and her family moved often; traveling from Missouri to Providence, Rhode Island, to South Bend, Indiana.

At 18 years old, Roberts moved to New York City, where she studied architecture at the Atelier Masqueray-Chambers from 1899-1901. The atelier was the first in the nation to teach architecture with the principles used by École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Architects Emmanuel Louis Masqueray and Walter B. Chambers founded the school to forge more rewarding educational and professional opportunities for women in architecture at the time.

Notable Works and Achievements

In 1901 after completing school at the Atelier Masqueray-Chambers, Roberts moved to Illinois to take a position under Frank Lloyd Wright in his Oak Park office. She worked with Wright alongside a team of six others, which included Marion Mahony Griffin, the only other woman in the group that would become known as the Prairie School.

Roberts’ impact while working for Wright is commonly underestimated as she contributed her design expertise to various projects, primarily after he left Oak Park for Europe in 1909. Some of her most notable projects include K.C. DeRhodes House in South Bend, Indiana – a commission for a friend of the Roberts family – the Laura Gale House in Oak Park and the Stohr Arcade Building in Chicago.

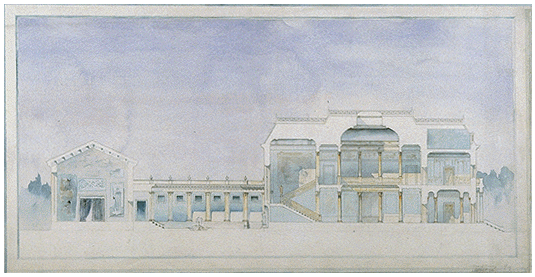

Commissioned by Isabel’s mother, Mary, the Isabel Roberts House in River Forest, Illinois, was another of Roberts’ illustrious designs with Wright. Completed in 1908, the home’s intricate arrangement contained a warm brick hearth at its core and utilized a mixture of half-story levels to connect living areas. The Prairie School design featured other innovative additions for the time, including a vaulted ceiling, diamond-paned windows and a grand octagonal balcony.