This fall, we honor the historical significance of 2019, which marks 100 years since the Bauhaus movement was founded. 100 Years of Bauhaus, a centenary exhibition, gives us the opportunity to look back on a school of thought that has not only influenced our own design, but the design and thinking of the world for over a century.

The Bauhaus School of Design was borne out of necessity 100 years ago during the harsh political climate of post-World War I Germany. Founded by architect Walter Gropius, the school sought to combat the rise of industrialist manufacturing that was swiftly outpacing human craft and comfort. The ease and speed at which product was created at that time had greatly diminished aesthetic value and the way that design affect those that interacted with it. Things were, quite literally, looking bleak.

The Bauhaus solution was to bring back craftsmanship, combined with fine arts to make it stronger. The school aimed to combine all art forms in order to create one unified piece of art that could bring a sense of beauty and wonder back to the viewer. The Bauhaus did this through a sharp focus on form, function and aesthetic, ultimately creating art products that were abstractly beautiful and evocative.

Most notable products of the Bauhaus school were furniture and wallpaper — including Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel “Wassily Chair,” inspired by his bicycle, and Josef Albers’ stacking tables.

In 1933, the school was closed due to the increasing pressues of Nazi Germany, causing its students and members to disperse across the world. As the disciples of Bauhaus spread, so too did its unique theory and ways of thinking and creating. The last director of the Bauhaus before its closing, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, came to Chicago, where he rethought and revitalized the architecture program and campus at Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). Mies’ vision for IIT earned the school the title of “the second school of design,” with the Bauhaus being the first. His involvement at the Bauhaus heavily influenced the new architecture program at IIT, and therefore influenced David Hovey Sr., co-founder of Optima, as he studied there years later.

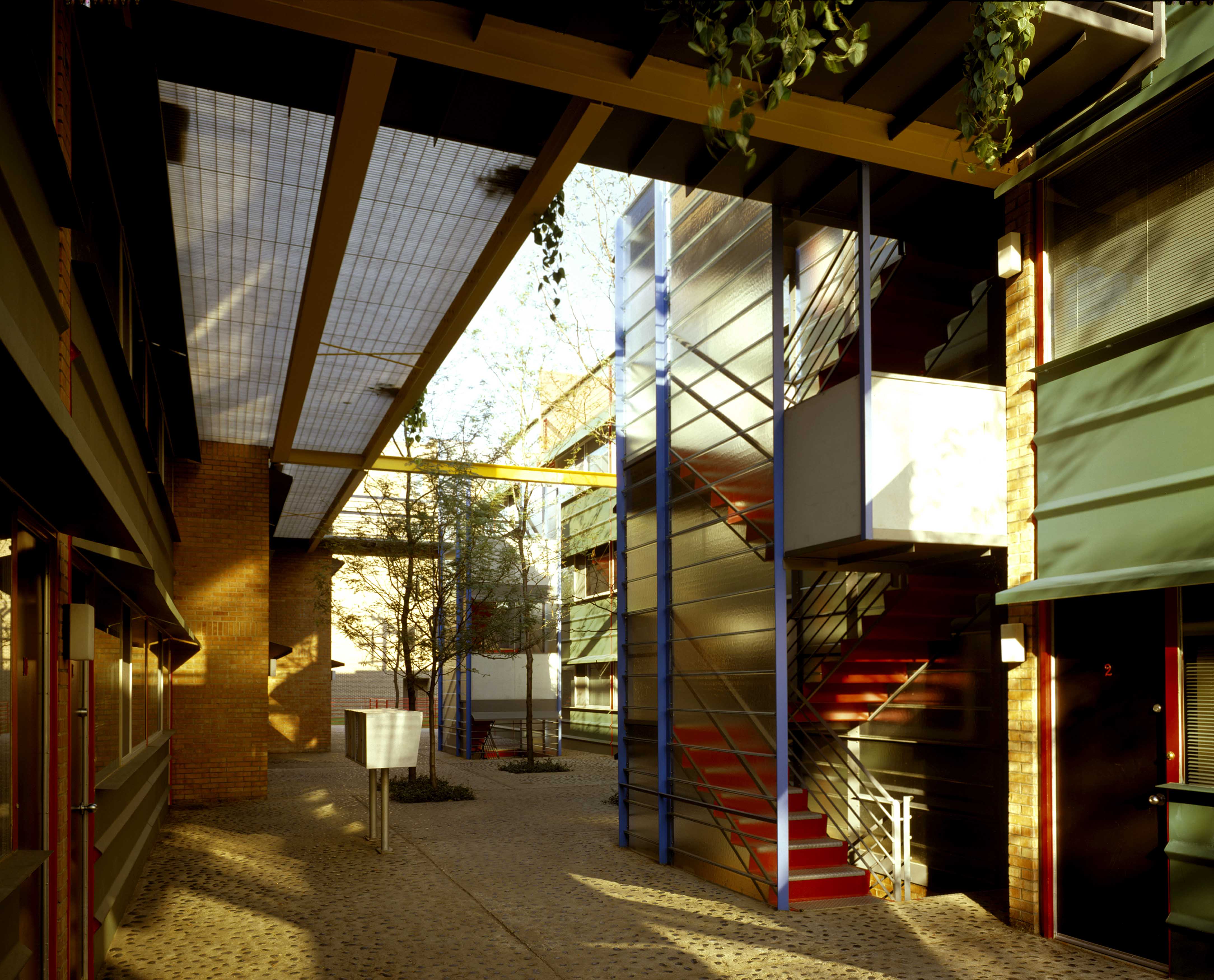

One can see the influence of the Bauhaus, Mies and the Modernist masters that came before us in the designs of Optima. Like the Bauhaus, we place a heavy emphasis on form and function in all that we design; and like Mies, our work places emphasis on open space and revealing materials. When Gropius first decided that the Bauhaus School of Design must involve all processes into the creation of one, higher art form, it set in motion the ideologies and design principles that have shaped who we are today.

Today, Bauhaus thoughts and designs continue to influence all fields of design — and if something isn’t made in the Bauhaus school of thought, it was probably made in counter-response to it. At Optima, we continue to be influenced by, and inspired by, the fascinating, careful and unique emphasis that the Bauhaus has brought to the way we create.