Sculptures are the ultimate exploration of materials and their expression. With Optima Co-Founder David Hovey Sr. having expanded the design reach of Optima to include sculpture, the medium is one that hits close to home for us. To indulge in our love for the craft, we’re exploring Chicago’s public sculpture art, piece-by-piece. First up is an iconic staple in Chicago: The Picasso.

The (Chicago) Picasso

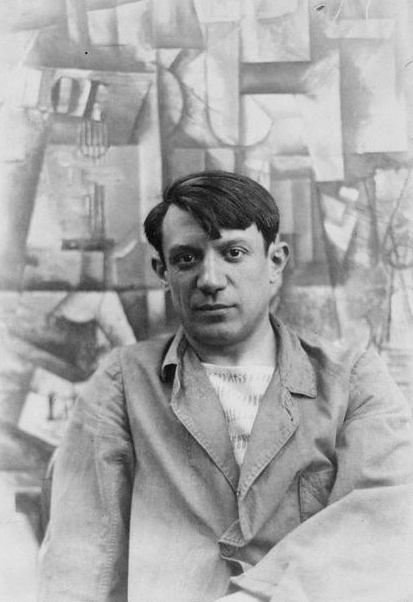

The monumental, larger-than-life sculpture created by Pablo Picasso situated in downtown Chicago goes unnamed by the artist. However, the work is affectionately referred to as The Picasso and even The Chicago Picasso. The sculpture is now a globally-renowned landmark, standing 50 feet tall and weighing in at 162 short tons.

The Chicago Picasso was commissioned by the architects of The Richard J. Daley Center in 1963. Occupying the beloved Daley Plaza alongside the skin-and-bones International Style Modernist skyscraper, the sculpture stands out as a whimsical and abstract piece that invites plaza visitors to jump, climb and slide upon its smooth, COR-TEN steel surface. The interactive sculpture cost the modern day equivalent of $2.8 million, with three charitable foundations shouldering the cost. And although Picasso himself was offered $100,000, he refused the payment, insisting that he wanted to make the work as a gift.

Picasso’s inspiration remains a mystery, though some muse that the armadillo-esque figure is actually an abstracted portrait of the French woman, Sylvette David – now known as Lydia Corbette. The sculpture’s abstract nature was met with tough criticism initially. In a city where most sculptures were famous figures, some didn’t take kindly to the strange public art newcomer. But it was only a matter of time before The Chicago Picasso rightly became a revered piece of Chicago’s vibrant public art collection, brightening the Daley Plaza and the city with its presence.