While conversations about the architectural greats center around figures such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright, there are countless powerful women whose names are left out. At Optima, we’ve celebrated the contributions of everyone from Charlotte Perriand to Ray Eames — and today, we’re spotlighting a few more women in architecture you should know.

Sophia Hayden

Sophia Hayden was born in Santiago, Chile in 1868 and moved to Boston at age six. Hayden discovered her interest in architecture during high school and went on to be the first female graduate of the four-year program in architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). She graduated in 1890 with honors. After college, Hayden initially struggled to find work in the male-dominated world of architecture and settled for a position as a mechanical drawing instructor at a local high school.

Only a year later, at just 21, Hayden jumped at the opportunity to enter her design in a competition for the Women’s Building at Daniel Burnham’s 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Her design won the competition and Hayden was awarded $1,000, a tenth of what male architects earned for similar buildings.

During construction, Hayden was micromanaged incessantly and had to make many compromises on her design. The stress of the situation led Hayden to a breakdown and she was placed in a sanitarium for an “extended period of rest.” After the incident, Hayden retired from architecture permanently. Her treatment and diagnosis of hysteria have much to tell us about the challenges women in architecture faced during this time.

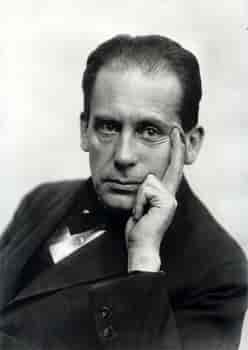

Marion Mahony Griffin

Marion Mahony Griffin was born in 1871 in Chicago, and at nine her family migrated to the suburb of Winnetka after the Great Chicago Fire. Watching a landscape consumed by growing suburban sprawl developed Mahony’s interest in architecture. She went on to graduate from MIT in 1894, becoming the second woman to do so after Hayden.

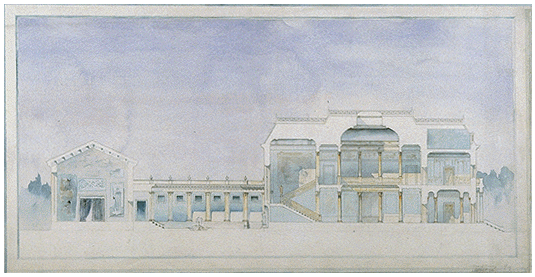

After college, Mahony moved back to Chicago and became the first woman licensed to practice architecture in Illinois. She found work at her cousin’s architecture firm downtown alongside Frank Lloyd Wright. There, she created beautiful watercolor renderings of buildings and landscapes — a signature style which would later be attributed to Frank Lloyd Wright. Mahony worked alongside Wright for fifteen years, contributing greatly to his reputation and success to little recognition. She was also an original member of the Prairie School of architecture.

When Wright eloped to Europe, he offered Mahony his studio’s remaining commissions, but she declined. Mahony is even rumored to have said Wright’s habit of taking credit for things, including the Prairie School movement, are what led to the movement’s early death. Later in life, Mahony collaborated with ex-Wright employee, Prairie School member and her husband, Walter Burley Griffin. Throughout her career, Mahony brought to fruition many notable projects, including Henry Ford’s Dearborn mansion and the Gerald Mahony Residence in Elkhart, Indiana.

Stay tuned for more features on women in architecture.