As a part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re spotlighting Georgia Louise Harris Brown, a visionary who was able to apply her extraordinary talents across the world. Although she rarely received credit for her outstanding contributions, Brown’s passion for building never diminished. Learn more about her impressive life and career below:

The Life of Georgia Louise Harris Brown

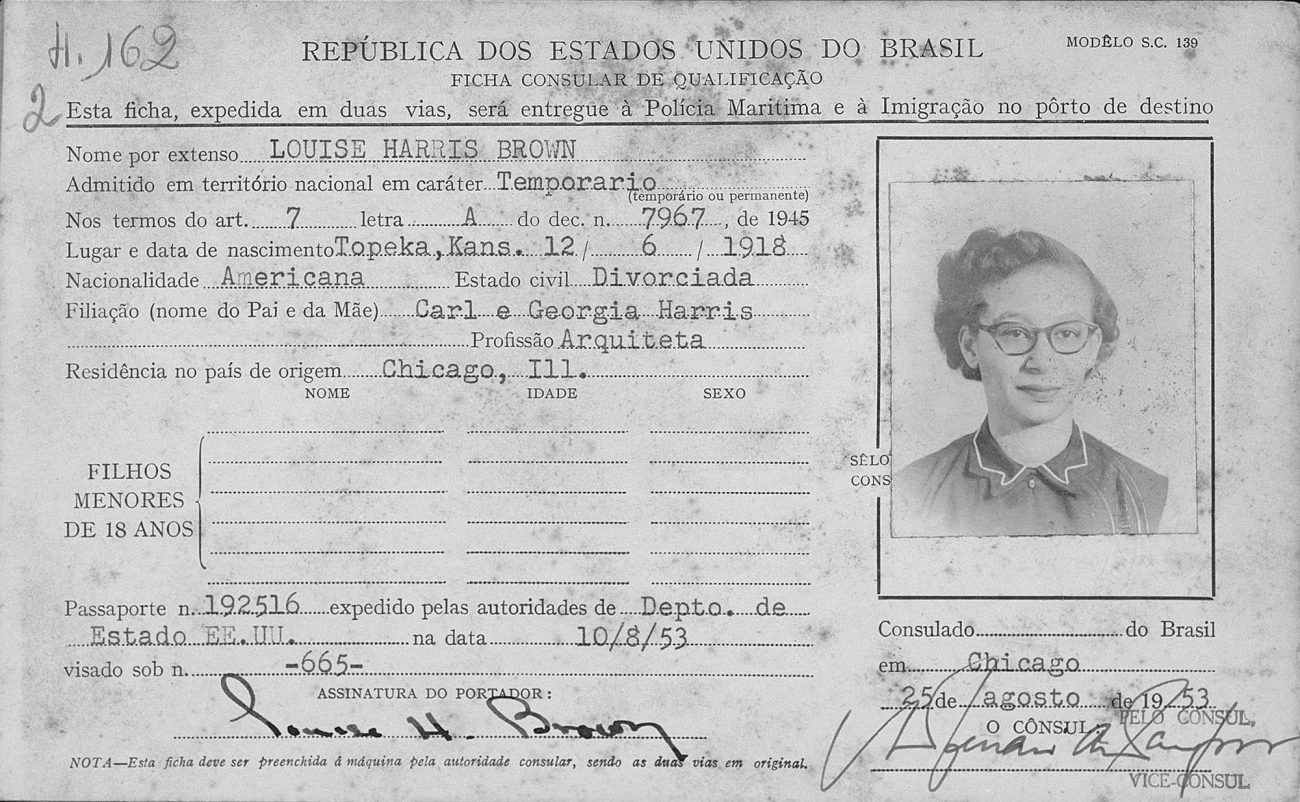

Georgia Louise Harris Brown was born on June 12, 1918, in Topeka, Kansas, to Carl Collins, a shipping clerk, and Georgia Watkins, a school teacher. As a child, her interests revolved around the arts and tinkering with cars and farm equipment with her brother. Brown distinguished herself from school as an exceptionally bright student, which led her to Washburn University, where she studied from 1936 until 1938.

After graduating, Brown traveled to Chicago to visit family but instead fell in love with the metropolitan atmosphere and presence of a strong Black community. Originally planning to stay for the summer, she enrolled in a course at the Armour Institute of Technology – now the Illinois Institute of Technology – taught by Mies van der Rohe and began taking flying lessons, which would become a lifelong passion.

However, her plans changed when she enrolled in the school’s engineering and architecture program in the fall of 1938. Brown continued her studies in architecture but moved back to Kansas in 1942. She completed her degrees at the University of Kansas in 1944 and was the first Black woman to do so at the school.

Notable Works and Achievements

Brown returned to Chicago in 1945, where she found a job working for Kenneth Roderick O’Neal, a confidant of Mies and a leading architect at the time. In Chicago, she acquainted herself with other aspiring Black architects, including Beverly Lorraine Green and John Moutoussamy. In 1949, while working for O’Neal, Brown finally received her architecture license, and in the same year, she began working for Frank J. Kornacker Associates, Inc.

At Kornacker Associates, Brown developed many structural calculations, including those for the apartment building at 860 Lake Shore Drive. During her time there, she also worked on many side projects for Woodrow B Dolphin, including various churches, houses and office buildings around Chicago. Although, after realizing that her race and gender would hold her back from many opportunities in America, she became interested in moving to Brazil, where she believed she would be held back less.

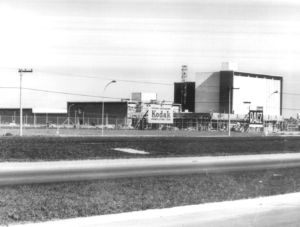

In 1953, Brown relocated to Brazil but didn’t receive an architecture license for the country until 1970. However, shortly after arriving, she found work with Charles Bosworth, another American who had moved to Brazil to open his own firm. While living in Brazil, Brown contributed designs and managed the completion of several significant builds. Along with various personal homes, many of her projects included large-scale plants and factories, including one for Ford Motors, Pfizer and Kodak.

While Brown’s contributions to architectural design have often been unrecognized, her expansive knowledge of structural engineering and design always drove her to the leading firm of the time. And while she contended with feeling like an “other” wherever she went, she never held back from challenging the status quo and pursuing her lifelong passion for architecture.