Our appreciation for Modernism extends past architecture into all mediums of creative thought, including our love for sculpture (and our own sculpture at Optima). Sculpture has long been an artistic expression across decades and culture, but the beginnings of Modern sculpture sparked with renowned visionary, Auguste Rodin.

Setting the Stage

By the 20th century, sculpture practices in Europe largely revolved around Neoclassical and Romantic ideals. Contour and clarity defined figures, and artists were inspired by the art and culture of classical Greek antiquity. Often sculptors even portrayed their subjects in Roman costume instead of contemporary clothing. But the world of sculpture would see dramatic change at the 1900 Paris Exposition, when Auguste Rodin would use the world’s fair to unveil a new way of thinking when it came to sculpted form.

Auguste Rodin

Rodin came from a working-class family in Paris and throughout his turbulent youth, taught himself to draw and paint. Eventually, he learned the trade of ornamental design and sculpture, but by the 1890s, had grown exhausted of the style. Rodin was a naturalist, more concerned with character and emotion than he was with tradition, idealism or decorative beauty. His work emphasized detailed, textured surfaces and the juxtaposition of light and shadow, a style that was met with criticism initially. At the Paris Exposition, Rodin showcased a series of pieces that would turn an entire industry upside down at the turn of the century.

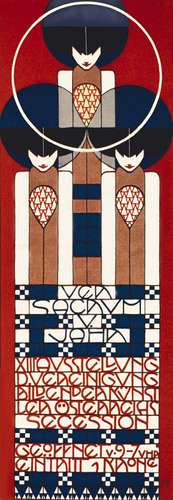

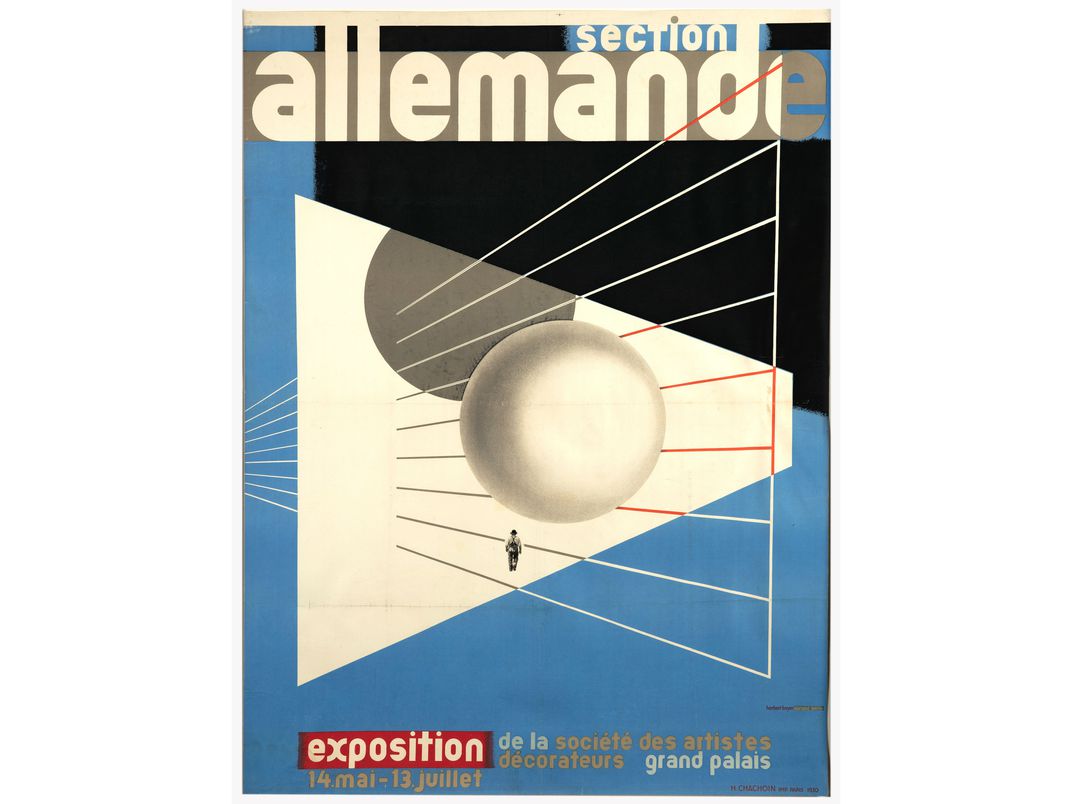

Modern Sculpture

Modernist styles that followed Rodin’s debut included Art Nouveau, Cubism, De Stijl, Dadaism, Surrealism, Futurism, among many others. It seemed that once the creative floodgates were open, artists ran with the possibilities of bending form past the boundaries of traditional realism. Especially since the 1950s, Modernist trends in sculpture have become increasingly more flexible to include new materials, abstractions and approaches. And we’re thankful they’ve made such progress; it’s allowed our own expressions of form to flourish over the years, and contribute beautiful, unique sculpted pieces to our Optima communities.