As part of our Women in Architecture series, we recently wrote a feature on pioneering architect, Norma Merrick Sklarek. Sklarek made waves when she co-founded her own architectural practice — the largest women-owned architectural firm in the country, and the first practice to be co-owned by an Black woman. That firm was Siegel Sklarek Diamond.

Siegel Sklarek Diamond

Siegel Sklarek Diamond was founded in Los Angeles in 1985 by three architects from whom the firm got its name: Margot Siegel, AIA, Norma Merrick Sklarek, AIA and Katherine Diamond, FAIA. Siegel had owned her own business for fourteen years prior, while Sklarek and Diamond both came from jobs working for large companies.

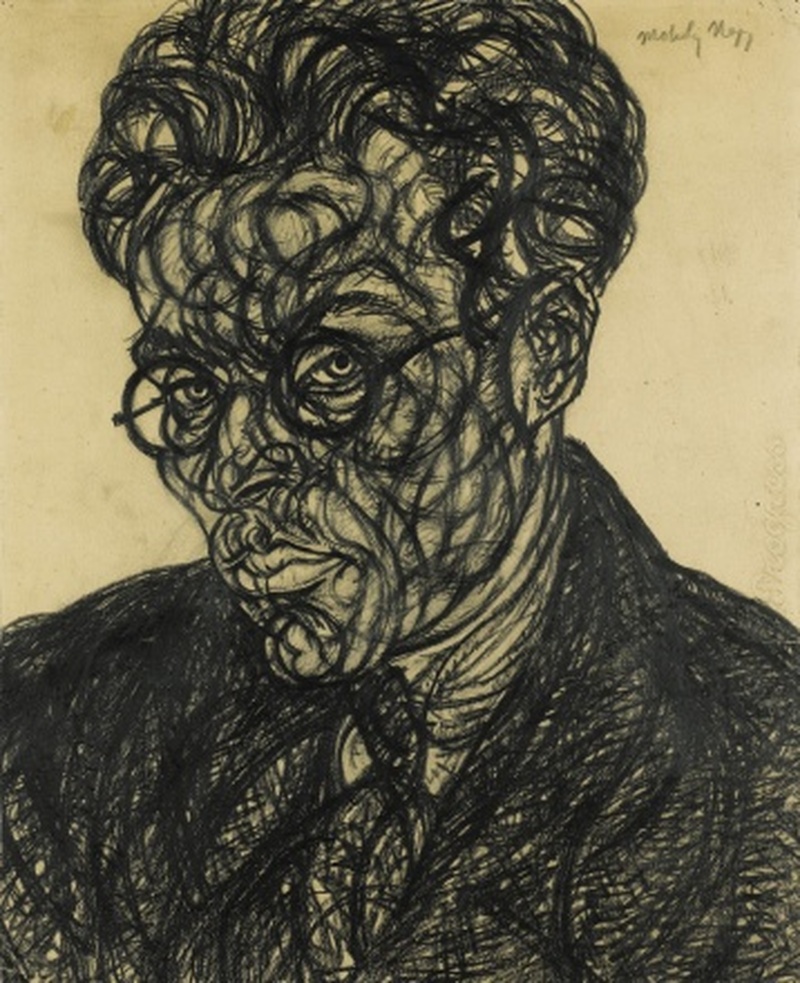

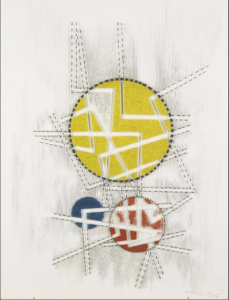

The trio combined their unique skill sets to build a successful and impressive practice. Siegel took on the task of quality review and preparing working drawings; Sklarek brought her impressive project management abilities and keen architectural sense; Diamond took charge of the design, giving shape to simple ideas and ensuring clients’ needs were met. Overall, their collective style took inspiration from the Bauhaus style, consisting of largely unadorned Cubist structures, but with the three women’s own inventive twist.

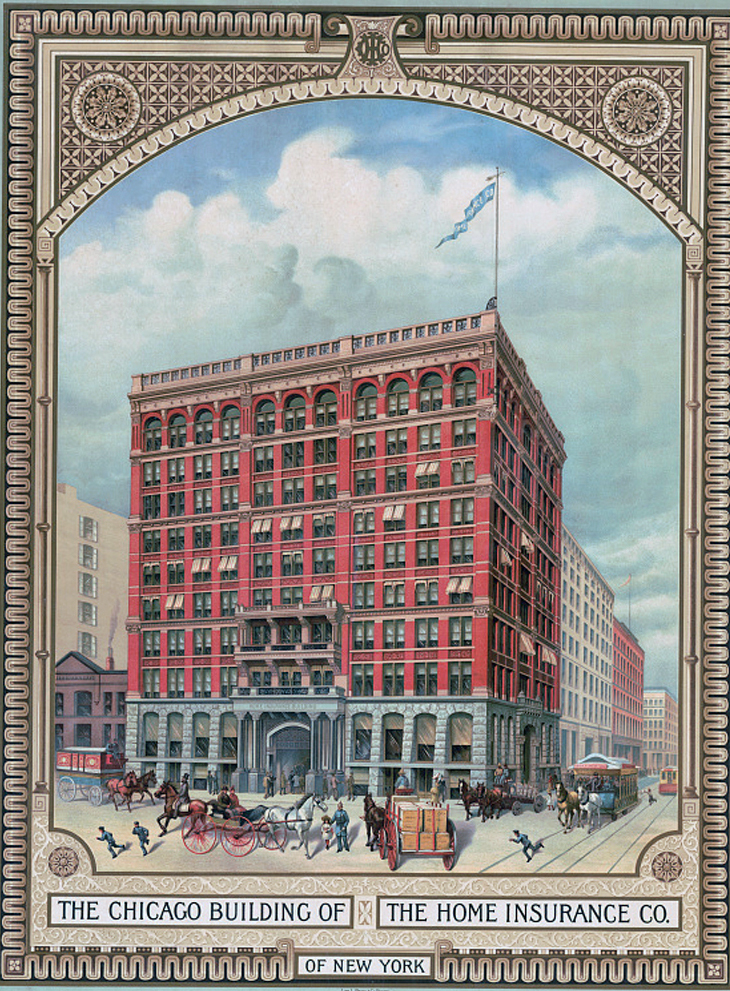

According to a Los Angeles Times article published the year after their founding, Siegel Sklarek Diamond, had “a portfolio of nearly a dozen large projects in Southern California with a value of more than $25 million.” Their work covered a broad breadth and depth of categories, including educational facilities and community buildings, as well as commercial and industrial projects. Projects Siegel Sklarek Diamond took on include the Student Counseling and Resource Center (1988) and The Early Childhood Education Center (1989) at the University of California, Irvine and the Los Angeles Air Traffic Control Tower (completed in 1995), among others.

In that same article, Diamond is quoted saying that the architecture profession at the time was “definitely an old-boys network,” Diamond said. “It’s definitely a very male-oriented profession, and I think that part (of the reason) is our clients, in order to have the money to hire an architect, tend to be older and more conservative.” As the largest women-owned architectural firm nationally at its time, and the first to be owned by a Black woman, Siegel Sklarek Diamond certainly turned that industry standard on its head and paved the way for many more influential women to follow.