At Optima®, we deeply appreciate the storied structures that enrich our understanding of local culture. In our “Then and Now” series, we’ve explored the fascinating evolution of significant buildings in Arizona. With our latest post, we delve into the rich tapestry of Phoenix’s past, with a spotlight on the Sahara Motor Inn, a former city icon that once personified the vibrant spirit of the Southwest.

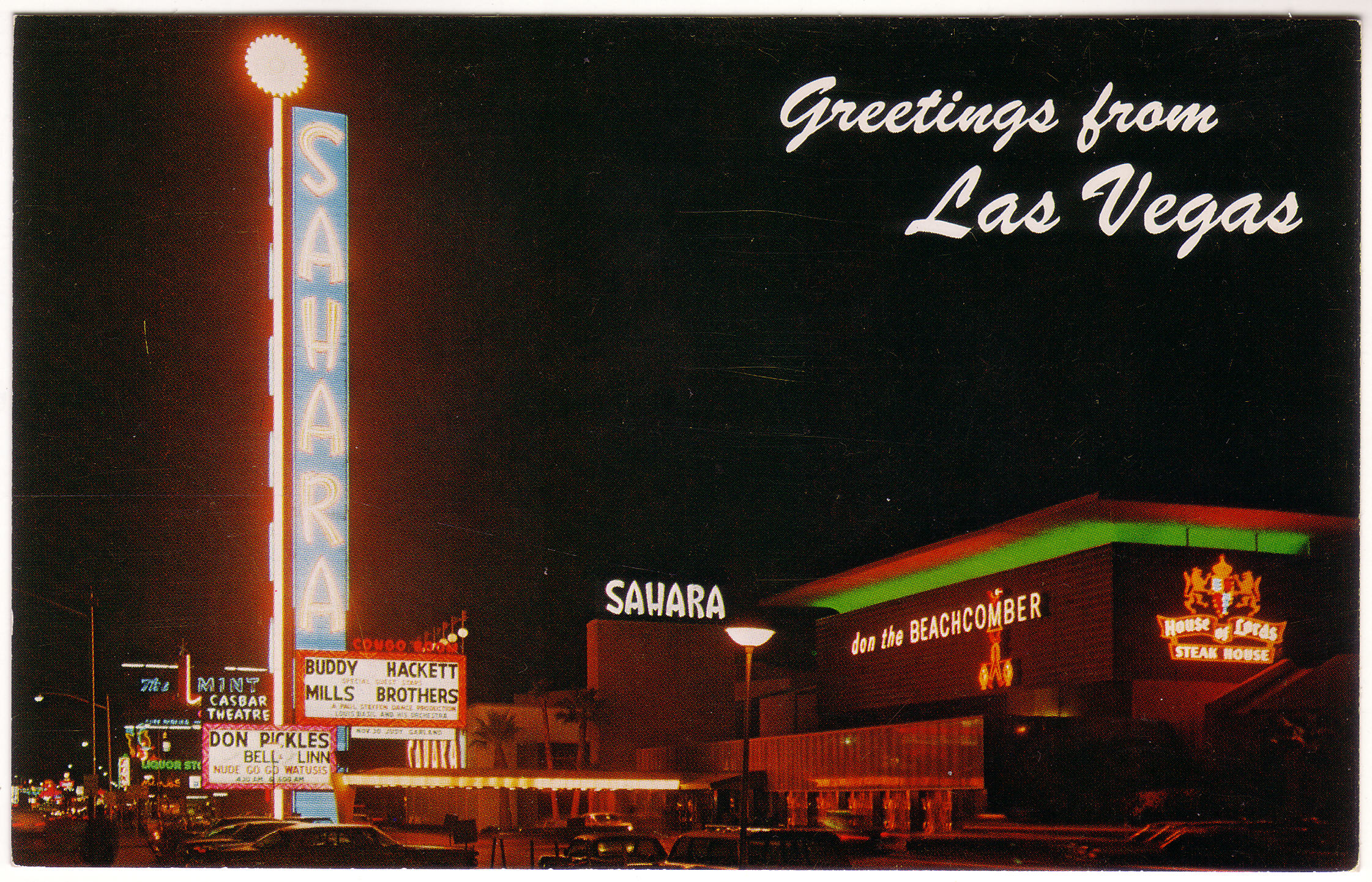

The Sahara Motor Inn opened its doors in 1955, built by an investment consortium led by notable figures, Marion Isbell and Del Webb. This mid-century marvel was much more than a hotel. It was a symbol of a thriving, evolving Phoenix, a testament to the rise of automobile culture, and an emblem of the burgeoning region.

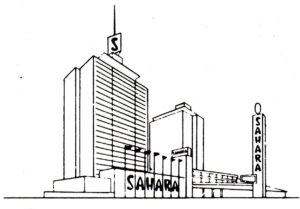

Designed by Matthew E. Trudell, the Sahara Motor Inn sprawled across a city block, boasting 175 guest rooms, two penthouse apartments, and a host of modern amenities. It wasn’t just the size or facilities that made the hotel stand out. The architecture, a harmonious blend of mid-century styles, utilized popular materials such as red brick, colored art glass, and cast-in-place concrete.

Renowned in its heyday, the hotel attracted a celebrity clientele including Marilyn Monroe, who resided there while filming Bus Stop in 1956. As time went on, the Sahara Motor Inn partnered with the Ramada Inn motel chain, becoming the “Sahara Ramada Inn” in the 1960s. The desert gem gradually faded, overshadowed by the expansion of large hotel chains that promised a consistent guest experience nationwide.

By 2000, the Sahara Ramada Inn was no longer the crown jewel of downtown Phoenix. The forces of redevelopment were sweeping through Phoenix, with civic leaders and universities envisioning a new era of urban transformation. The hotel was sold to Arizona State University (ASU) in 2010 and was later razed to make way for the university’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

The story behind Motor Inn is a classic narrative of transformation, encapsulating the spirit of change so familiar in Phoenix. From its birth as a luxury hotel in the heart of the American Southwest to its rebirth as an educational institution, its journey mirrors that of the city itself.

The story of the Sahara Motor Inn still stands, even as the building itself is no longer a part of the city’s architectural landscape. It remains a tale of a bygone era, a time of profound change and growth, underlining the relentless momentum of progress.