Chicago is home to a diverse array of styles and voices that have forever marked architecture in the city, and in the world. In our Chicago Skyscraper History series, we’re taking a magnifying lens to the skyline and looking at the unique buildings and stories that define it. Today, our focus is on the iconic Tribune Tower.

A Historic Landmark and Event

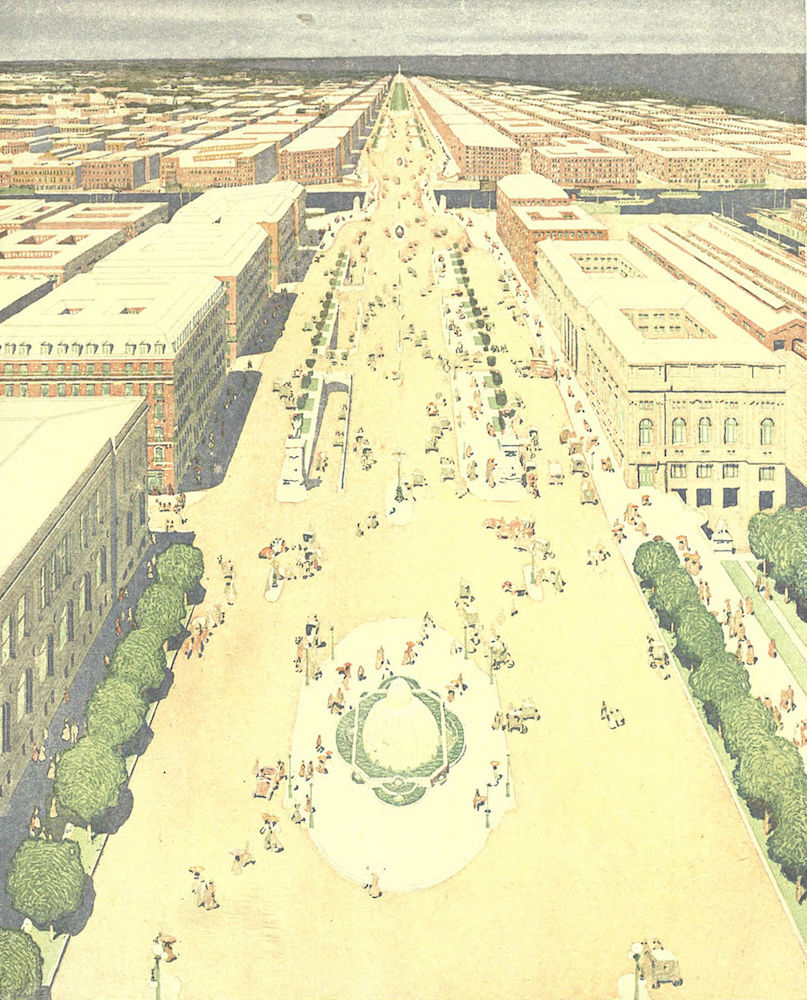

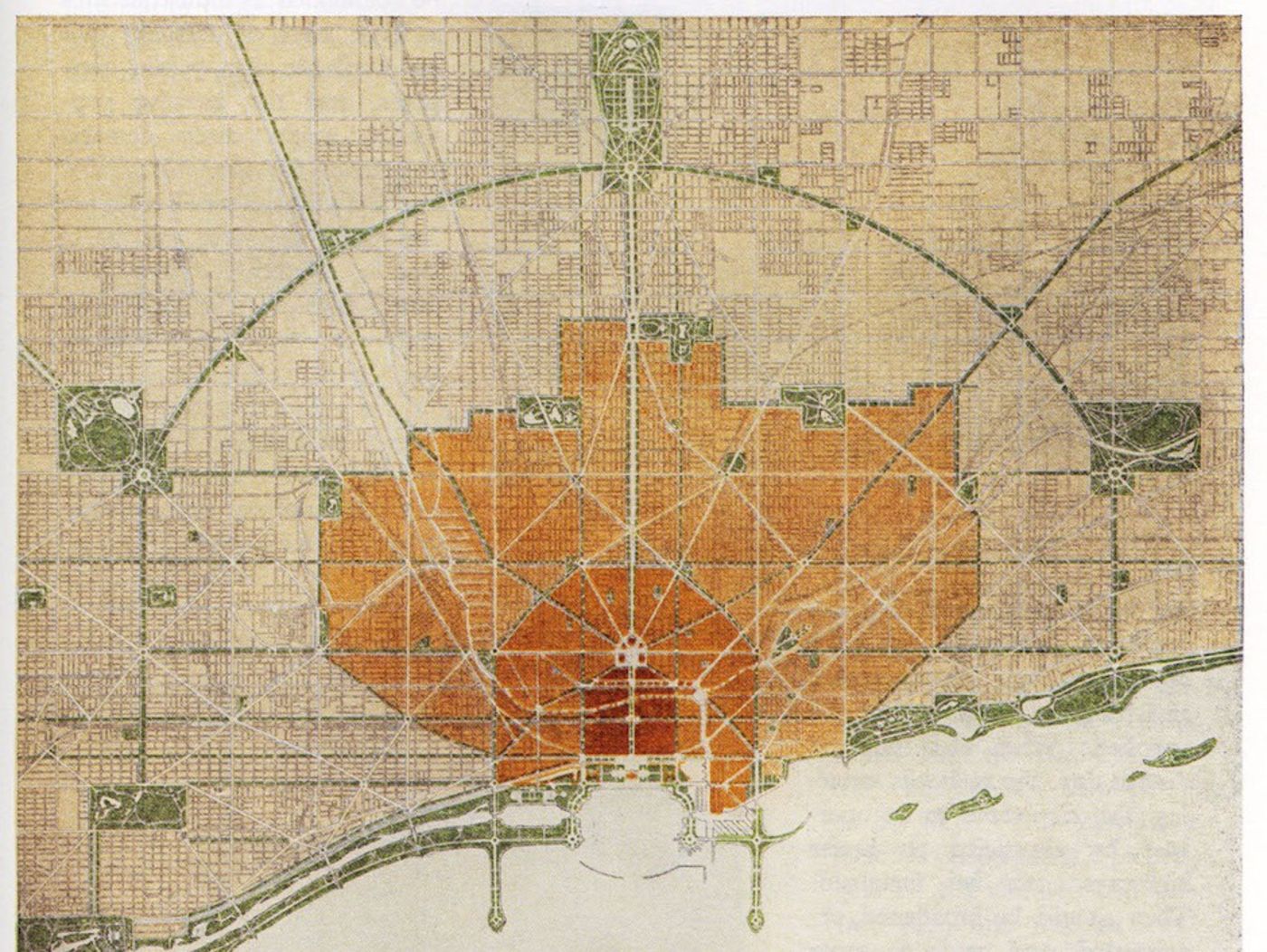

While the original Tribune Tower was built in 1868, it was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire in 1871. The iconic neo-Gothic tower as we know it today rose from the ashes of that tragedy. Hoping to replace the home they’d lost, the Chicago Tribune hosted a design competition in 1922 inviting architectural firms internationally to submit proposals for their new headquarters, in celebration of the paper’s 75th anniversary. The first prize proposal would receive $50,000 for “the most beautiful and distinctive office building in the world.”

In total, 260 entries were received by architectural greats such as Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen and Bauhaus-founder Walter Gropius. While many entries received critical acclaim during the widely-publicized competition (and are archived today at the Art Institute of Chicago), the first-prize spot went to New York architects John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood.

The neo-Gothic design from Howells & Hood features ornate buttresses at the peak of the tower, which can be seen peeking out above the city skyline, illuminated at night. The highly decorative tower features details such as carved images of Robin Hood (representing architect Raymond Hood) and howling dogs (representing architect John Mead Howells), as well as countless gargoyles — one of which is a frog.

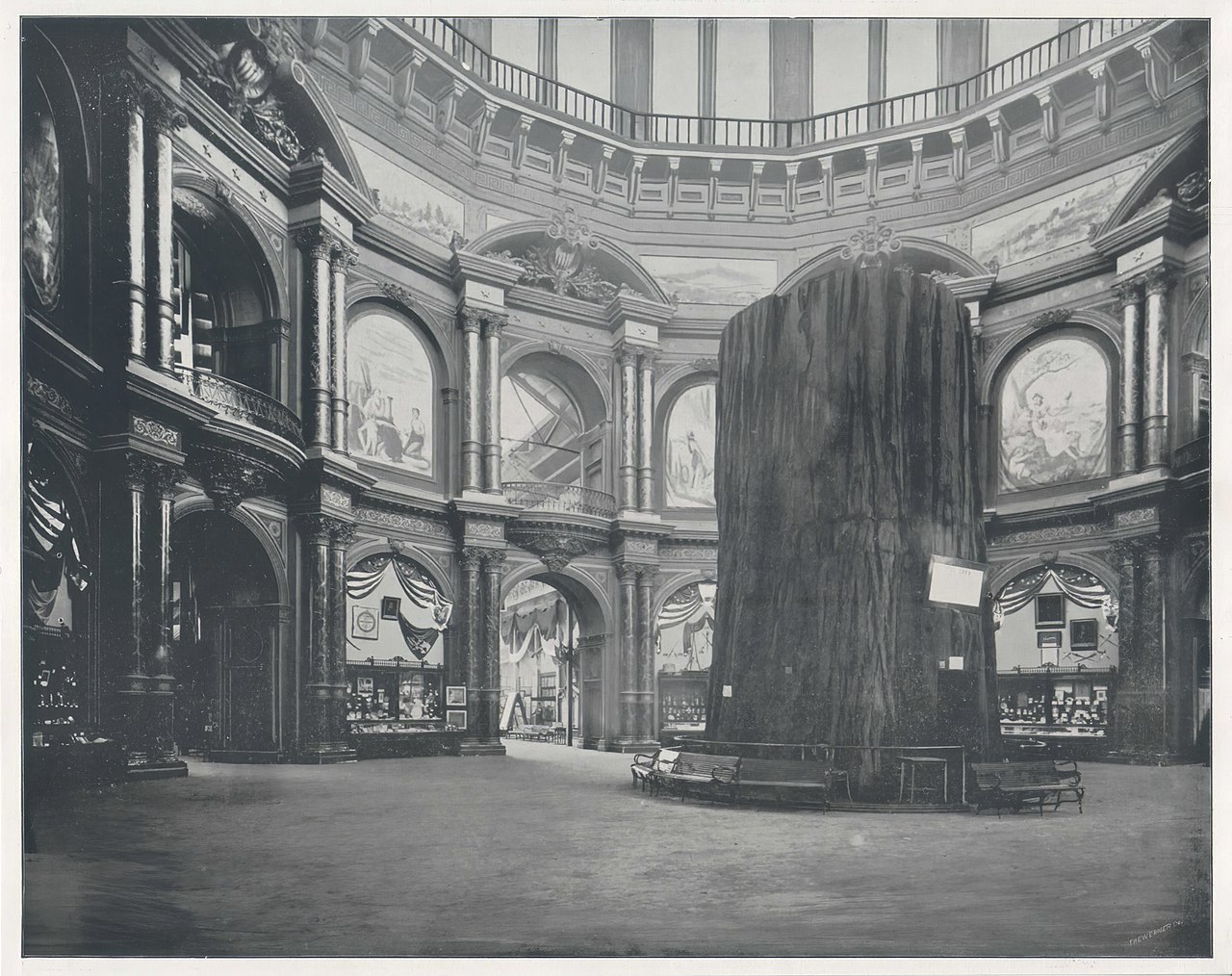

The lowest levels of the building also feature rocks and bricks from numerous historically significant sites across the world. These 149 special fragments include stones from the Great Pyramid, Abraham Lincoln’s tomb, Notre Dame de Paris, the Great Wall of China, Taj Mahal and even petrified wood from the Redwood Forests. From 1999-2011, the building even featured a Moon rock, brought by Buzz Aldrin on loan from NASA.

The tower, which is a Chicago landmark and part of the Michigan-Wacker Historic District, has been home to the Chicago Tribune, Tribune Media, Tribune Publishing and WGN Radio. Most recently in early 2018, work began to convert the entire office building into ultra-luxury condominiums. The building’s neighborhood, Streeterville, is also home to our Optima Signature and Optima Chicago Center residences. We’re biased, but we love the history and significance the neighborhood holds to the city.

No matter its function, the Tribune Tower will always remain a remarkable part of architectural history, in both Chicago and the world.