With aligning principles, artists and aesthetics, our practice of Modernism and the Bauhaus movements often overlap. Chicago’s Bauhaus movement offered unique contributions to the city’s growth, and continues to inspire. Today, we dive into its past and its present impact.

Troubled Beginnings

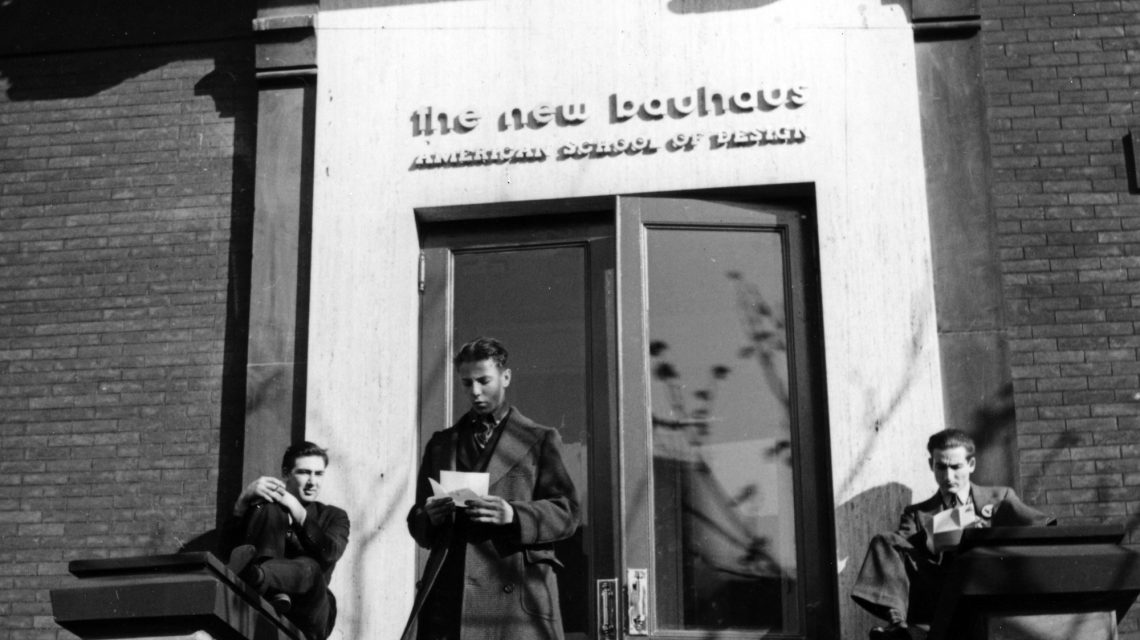

During WWII, many artists and instructors involved with the Bauhaus movement were forced to flee Germany (you can read a more in-depth history on our past blog post,100 Years of Bauhaus.) A group of instructors took refuge in the United States, a few taking particular interest in Chicago and the Midwest. Among them was László Moholy-Nagy, who was enlisted by the Chicago Association of Arts and Industries to help open a similar Bauhaus school to attract talent. With Moholy-Nagy’s eccentric leadership, The New Bauhaus was born.

An Expansive Practice

Considering its widespread impact on the art world and Chicago, The New Bauhaus was a short-lived school, its formation filled with dramatic disagreements between leadership and changes in locations. Moholy-Nagy and other teachers built an atypical educational experience that produced eccentric, groundbreaking artists; however, the work they produced wasn’t particularly practical or profitable. After his death, the school was absorbed by the Illinois Institute of Technology and transferred to the care of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Despite its turbulent trials, Chicago’s New Bauhaus school influenced many artists and industries, ranging from textiles and furniture to photography and sculpture. Ludwig Hilberseimer, another German immigrant, made notable strides in urban planning. Nathan Lerner and Art Sinsabaugh helped define the visual culture in Chicago. Emmett McBain had a remarkable impact on the representation of Black Americans in advertising. Often overlooked through the lens of history, the women active in Chicago’s Bauhaus movement had impactful careers as well, from Marion Mahony Griffin’s architectural and planning work and Elsa Kula’s colorful, eye-catching work.

From architecture and urban design to painting and sculpture, the legacy of the Bauhaus is evident throughout Chicago. And ultimately, its relationship with Modernism naturally means it’s also reflected in our own buildings and sense of design.