At Optima®, we’ve always believed that architecture is more than just buildings — it’s about creating environments that enrich lives. Today’s architectural innovations are showing remarkable potential for enriching lives, and specifically for supporting individuals with memory loss, offering not just safety and comfort but also a touch of joy in their daily lives.

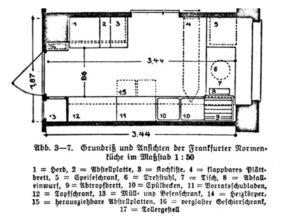

Imagine a space that’s easy to navigate, where each corridor and room feels familiar and safe. This is the main goal when designing for dementia care. Simple layouts and clear signs help reduce confusion, making spaces feel more like a home and less like an institution. Safety is also paramount, but so is the freedom to explore. Thoughtful design usually includes secure outdoor spaces where residents can enjoy a bit of nature without the risk. Indoors, non-slip floors and good lighting are essentials, not afterthoughts.

But it’s not all about functionality. Sensory engagement through architecture can bring immense comfort. Picture a room bathed in natural light, offering views of a serene garden, or the soft melody of a familiar tune playing in the background. These elements can awaken memories and provide a sense of calm to those with dementia.

Social spaces are also crucial to these designs. A well-designed common area can invite residents to interact, participate in activities, or simply enjoy each other’s company, all of which are vital for emotional well-being.

One of the leading examples of architecture designed to combat these diseases is the Alzheimer’s Village in Dax, France, the first of its kind in the country. Designed by the Danish architecture studio NORD Architects, the village features a handful of design elements that pull from Dax’s old town to create sensory familiarity for its residents.

The Alzheimer’s Village design is one brimming with intention. Pulling on the ideas of recognition and readability, the village is arranged in a bastide-like structure, broken up into four clusters that each house around 30 residents. The village features a grocery store, a restaurant and a hairdresser in its main square to help welcome familiarity. The thoughtful design, however, goes much deeper than just the facilities.

NORD architects purposely used local materials like timber planks, plaster and clay tiles to bring forth textures, colors and forms that are familiar to the residents. Other design elements, like the pattern of concrete arches and the inclusion of gardens and greenery throughout the community, all call back to the bastide design of old Europe.

Architecture, in its most profound sense, is about creating spaces that resonate with human needs. For those living with dementia, a thoughtfully designed environment, like the Alzeimer’s Village, can offer a semblance of normalcy, comfort, and dignity. It’s a bridge between the challenges of memory loss and the pursuit of a fulfilled life.