In the same way our own practices at Optima are rooted in and inspired by Modernist design, so too is the work of other architects and designers across the decades, and across the world. One of the joys of our industry is seeing how design translates through the lenses of other cultures and countries, and Modernism and Japanese Architecture have a truly fascinating connection.

The History

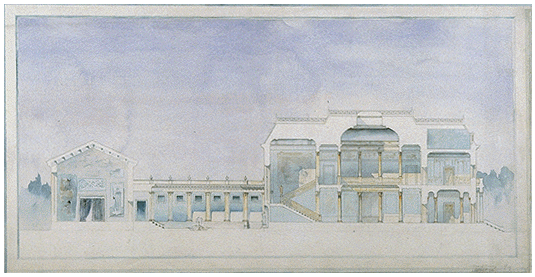

The Modernist movement began in the early 20th century, pioneered by architects such as Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. Le Corbusier, who traveled extensively during his lifetime, drew inspiration from traditional Japanese homes, sukiya-zukuri. Influenced by teahouses, sukiya-zukuri typically includes modest spaces designed with natural materials such as wooden columns and earthen-plaster. Pillars support the structure of the home, which allows for sliding screen walls to filter natural light into the rooms and blurs the barrier between outdoors and in. Le Corbusier used similar designs across his work, creating a connection between Japanese and Modernist architecture that only continued to grow.

In the 1930s, Japanese architects such as Junzo Sakakura and Kunio Maekawa collaborated with Le Corbusier, further fusing the two styles. Sakakura eventually rose to the chief of staff of Le Corbusier’s atelier in Paris, working on projects such as the 1932 Swiss Pavilion, which included sliding windows and open space for nature to flow in and out. The progress made from these collaborations impacted both Modernism and Japanese architecture — then and now.

Influences Today

Japanese influences are apparent across many executions of Modernist design. Intentional materials (whether they consist of wood, stone or metal), open floor plans and clean, minimalist spaces are present in both practices. Green space or gardens is also a huge similarity; and one we incorporate across all of our Optima projects. Through noticing and appreciating where these styles originate, we gain a greater knowledge and understanding of the world of architecture, and architecture throughout the world.