At Optima®, we have an unending fascination for architectural masterpieces, especially those that have shaped and defined the Modernist movement. Today, our focus rests upon an extraordinary residence, the David and Gladys Wright House, designed by none other than the father of architecture himself, Frank Lloyd Wright.

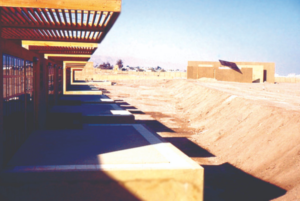

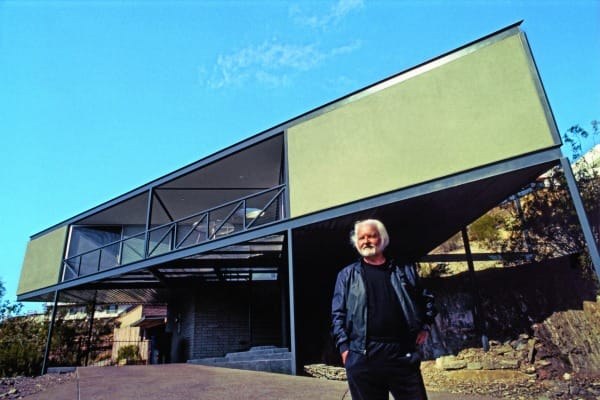

Located in Phoenix, Arizona, this house stands out as one of Wright’s most innovative residential designs. Constructed in 1952 for his son David and daughter-in-law Gladys, this home reveals the intimate connection Wright shared with his family, articulated in his distinctive architectural language.

Crafted towards the end of his prolific career, the David and Gladys Wright House reflects Wright’s refined understanding of organic architecture and his remarkable ability to adapt to the character of the site. The house, built with native concrete blocks, rises in a spiral form from the desert landscape, its curvilinear design echoing the shape of the nearby mountains.

The unique spiraling form of the house is a significant departure from the typical linear construction seen in many of Wright’s works, and it manifests his deep reverence for the natural world. The spiraling design ascends gracefully from the ground, turning 360 degrees to provide panoramic views of Camelback Mountain and the surrounding landscape.

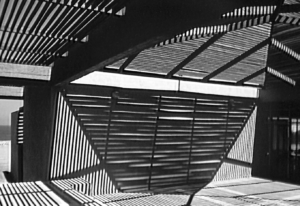

Inside, Wright’s naturalistic design philosophy continues — the interior floor plan unfolds like a nautilus shell, with rooms radiating from the central hearth, embodying the hearth’s symbolic role as the heart of the home. The characteristics Wright touches—built-in furniture, extensive use of natural light, and harmonious color palettes—are in full swing here, creating a seamless dialogue between the exterior and interior spaces.

Notable, too, is the home’s thoughtful integration of modern technology for its time. It was designed with innovative features such as energy-efficient passive solar heating, natural cooling, and a functional, open kitchen that was ahead of its time.

Despite facing threats of demolition, the house has been preserved thanks to the concerted efforts of preservationists, historians, and fans of Wright’s work. Today, the David and Gladys Wright House stands as a testimony to Wright’s genius and his enduring influence on Modernist architecture.

At Optima®, we’re continually captivated by such Modernist masterpieces that speak volumes about the era’s architectural ethos. Frank Lloyd Wright’s David and Gladys Wright House, with its distinctive design blending built form and natural environment, remains a profound source of inspiration and a vivid embodiment of Wright’s creative brilliance.