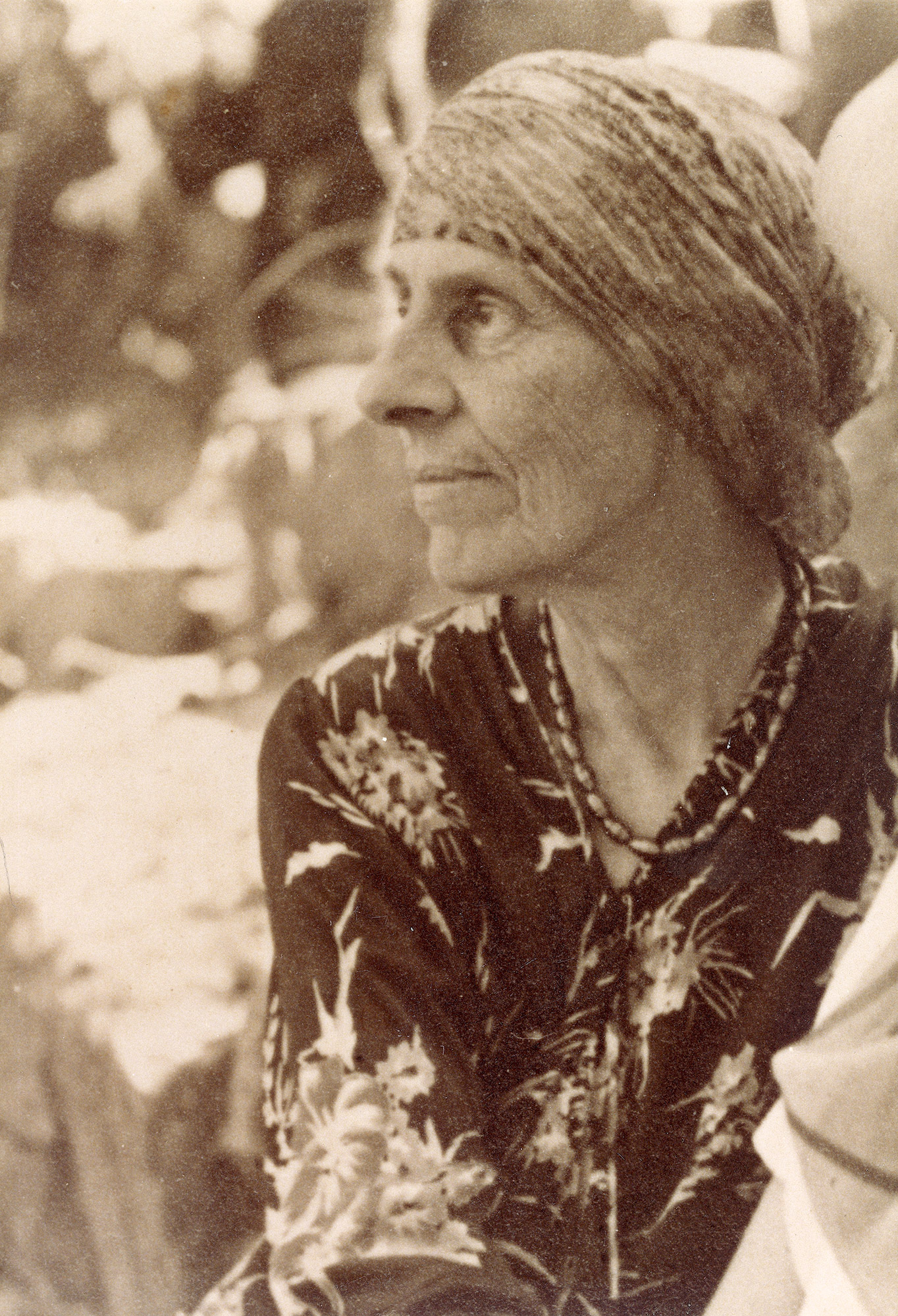

Often unrecognized for her immense contributions to the Prairie School, Marion Mahony Griffin was a leader in the architectural world for many years, paving the way for the countless women who followed her. Today, as part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re exploring the inception of the iconic architect and designer and where her extensive experience led her.

The Life of Marion Mahony Griffin

A Chicago native, Mahony was born in 1871 to Jeremiah Mahony, a journalist, and Clara Hamilton, a teacher. After the tragic events of the Great Chicago Fire, in which her family’s house was destroyed, her family relocated to the Chicago suburb of Winnetka where she spent the majority of her childhood. Inspired by how rapidly the landscape around her was changing — and encouraged by her cousin Dwight Perkins, an American architect — Mahony was drawn to the idea of furthering her education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Mahony graduated from MIT in 1894 and was only the second woman to receive an architecture degree from the school (after the World’s Columbian Exposision’s Women’s building designer, Sophia Hayden). She soon moved back to Chicago where she became the first woman in modern history to sit for, and be granted, an architectural license in the United States, benefiting from the fact that Illinois was the first state in America to allow women to hold licenses.

While in Chicago, Mahony spent two years working with her cousin Dwight Perkins at his studio in Steinway Hall (which Perkins also designed), where a diverse crowd of innovative artists and architects from the Prairie School could always be found. Soon after she left her cousin’s firm, she discovered another young Chicago architect also working in the building, Frank Lloyd Wright. Hired as Wright’s first employee, Mahony worked on and off with him for the next 14 years and became a significant contributor to his practice.

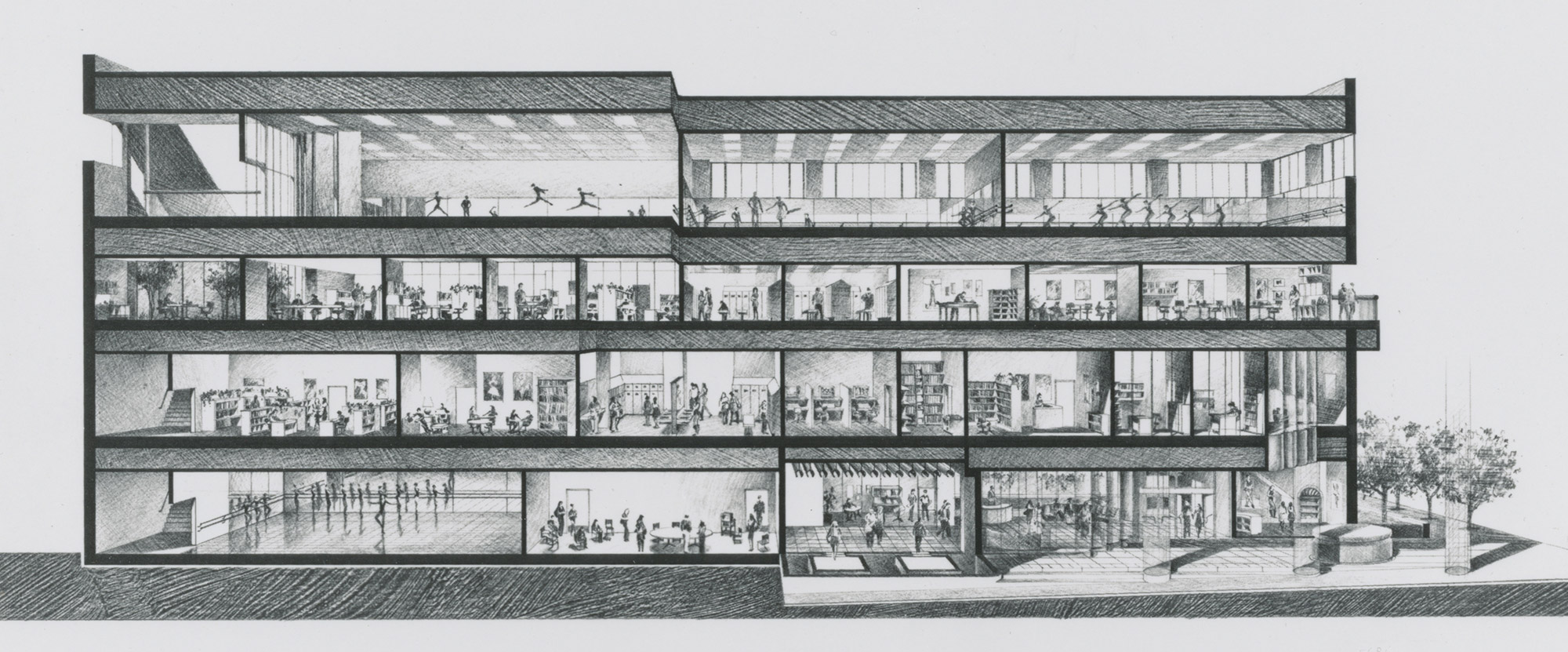

Ward W. Willits House, Highland Park, Illinois, 1902, One of the numerous intricate watercolor renderings Mahony created for Wright during her employment, Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

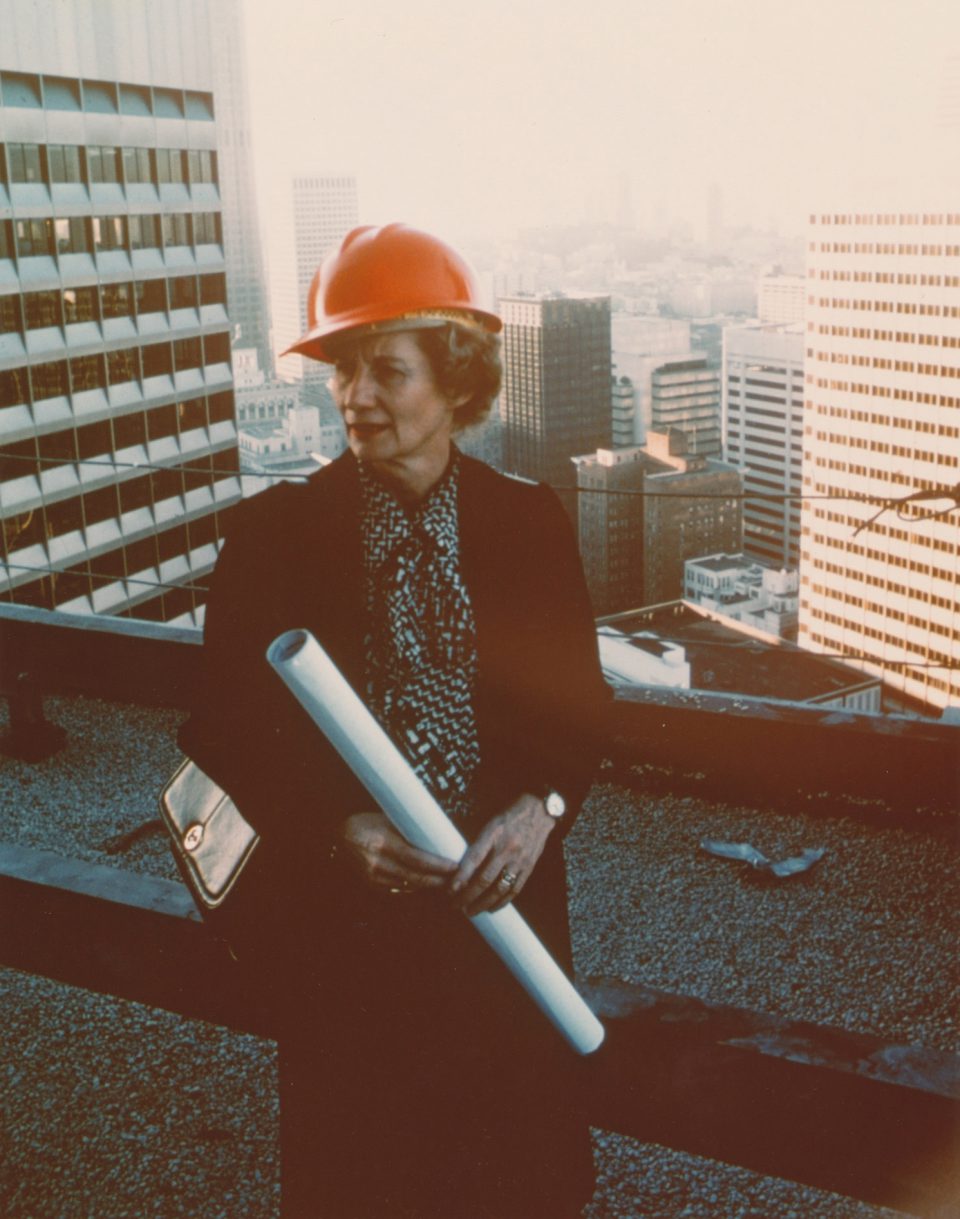

Career and Achievements

While working for Wright, Mohony provided intricate architectural renderings for his designs, becoming an essential participant in his work and leaving her without credit — a recurring theme throughout her career. Today, the renderings are acknowledged as her creations and she is recognized as one of the greatest architectural illustrators.

Mahony completed numerous independent projects while working for Wright including Evanston’s All Souls Unitarian Church. The intimate church featured an abundance of alluring stained glass in its skylights, windows and numerous other light fixtures.

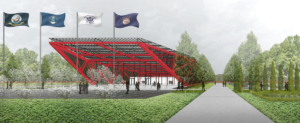

Eventually, Mahony left Wright’s studio to work with her husband, Walter Burley Griffin, a fellow architect and leading member of the Prairie School. Together, Griffin and Mahony created their most renowned work, the design of Prairie School residences in Mason City, Iowa, Rock Crest – Rock Glen. The nationally-recognized historic district features eight elaborate Prairie School homes that surround the city’s Willow Creek.

In 1914 the couple relocated to Australia, where Mahony’s watercolor renderings of Griffin’s design were chosen as the plan for the country’s new capital, Canberra. In Australia, Mahony’s commission’s increased dramatically. One of her final and most well-known works is Melbourne’s Capitol Theatre. The theatre’s opulent decor and avant-garde ceilings and walls were designed to invoke a crystalline cave, and showed a new side of Mahony’s architectural gifts.

Today, Mahony’s extensive experience and portfolio speak for themselves, and she is finally recognized as a trailblazer for architecture and design, and as an original member of the Prairie School.