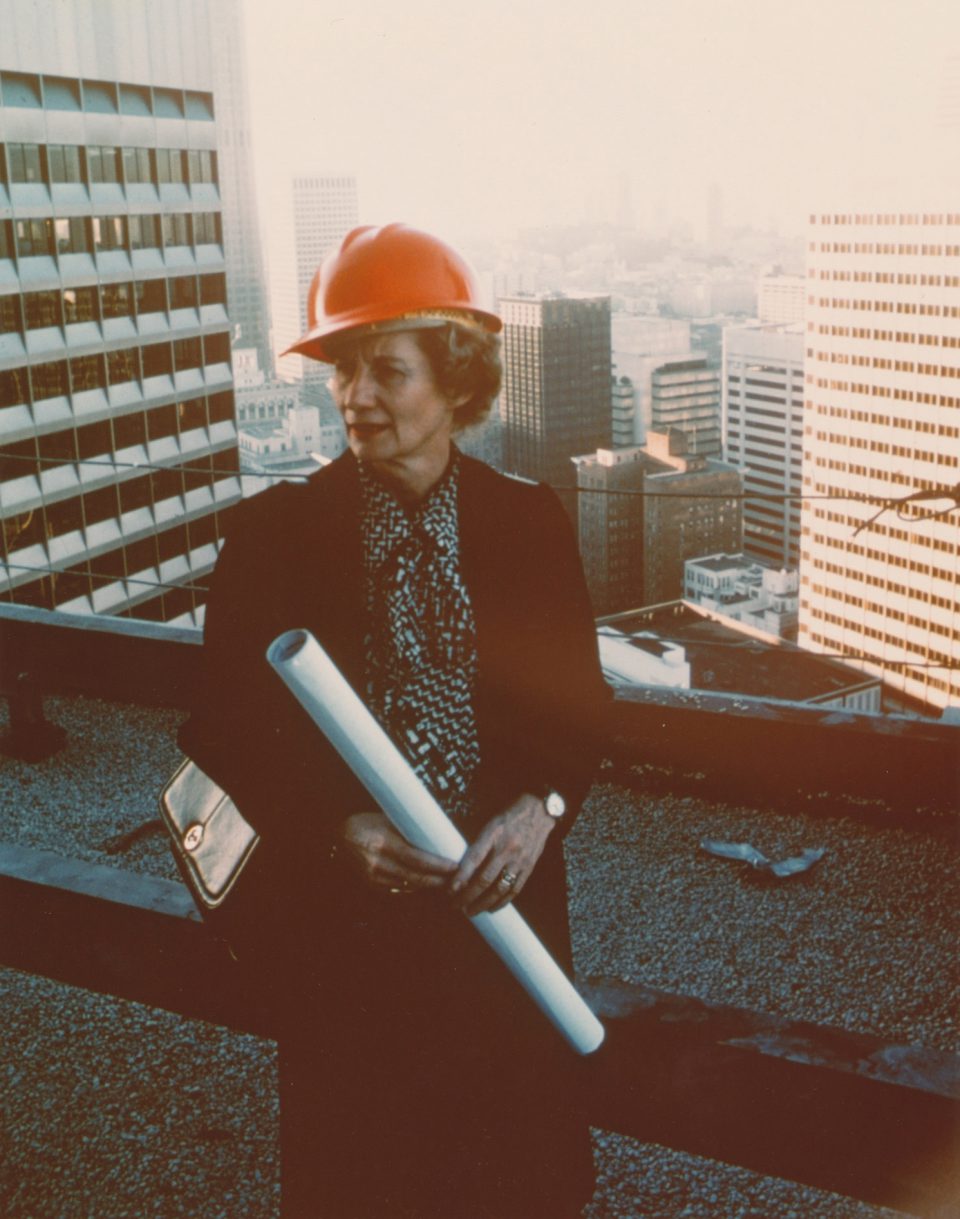

As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series at Optima, we’re taking a look at another pioneering female figure: Beverly Willis. Willis’ career set an unprecedented tone in the industry – to quote her own website, she “accepted commissions for which there were no built precedents, adopted practices that did not become mainstream until decades later, and sought research-driven solutions unique to each project.” Let’s dive in below:

The Life of Beverly Willis

Beverly Willis was born on February 17, 1928, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Her mother was a nurse and her father was an oil industry entrepreneur and agriculturist. The couple split during the Great Depression, at which point Willis was only six years old, and she wouldn’t see her father again for another several years. Left alone, Willis’ mother struggled to provide for her two children and they were placed in an orphanage. There, they worked for their keep and often fought back against the establishment, learning the lifelong lesson that “pushing boundaries was a way to survive.”

Willis saw her father again, for the last time over the summer when she was fifteen. She worked alongside him in his shop and earned a man’s wages, which she later used to pay for flying lessons. It was 1943, the middle of World War II, and with her ability to fly a single-engine propeller plane, Willis qualified for the Women’s Air Service.

After her time in the service, having learned many trades’ skills, Willis went off to study engineering at Oregon State University. Ultimately, however, she graduated with a Fine Arts degree from the University of Hawaii in 1954.

Career and Accolades

Willis learned much from her art studies and mentors – including Gustav Ecke, a scholar of Chinese furniture, who introduced her to Asian art and architecture, and Jean Charlot, who exposed her to the history of European art and fresco painting. Armed with this knowledge, she founded her own studio, the Willis Atelier, in Waikiki, Hawaii. There, she continued her murals, fresco paintings and multimedia installations. One of her most notable projects during this period was her fresco work on the Shell Bar at the Hilton Hawaiin Village hotel, which also used an innovative sand cast mural panel technique she herself had pioneered.

In 1958, Willis moved to San Francisco where she opened her own design office and deepened her architectural prowess. She was successful in retail design in particular, but transitioned to residential design with her special program at the Robertson Residence. There, she created notably disability-friendly design far before disability guidelines such as the ADA ever existed.

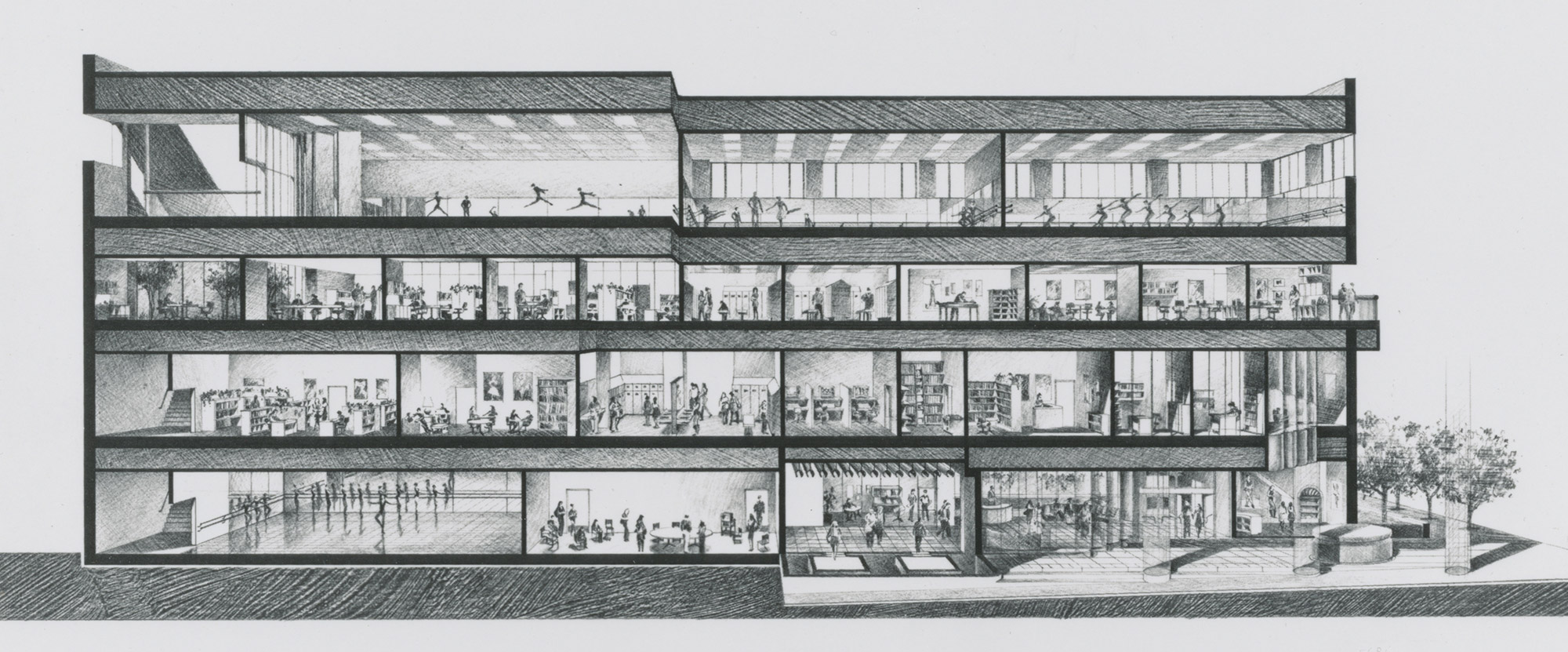

Two other notable projects during this era included her renovation of the Union Street Stores from 1963 to 1965, which, according to The Architectural Forum, “some historians describe as an initial contribution to the advancement of the Modern adaptive re-use of historical buildings movement.” She also designed the San Francisco Ballet Building in 1973. It was the first building in the US specifically designed for a ballet company and school, and paved the way for many others like it to follow.

Willis was also famously one of the first to use a computerized approach to design. Her firm invented CARLA (Computerized Approach to Residential Land Analysis) in 1970, a program which was quickly adapted and used nationally. In 1997, the National Building Museum published her book, “Invisible Images– The Silent Language of Architecture.” Understanding that women were often excluded from the historical narrative of architecture, Willis also founded the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation (BWAF) in 2002 with the goal of changing architecture culture through research and education.

Her extensive portfolio and accolades speak for themself. And lucky for us, today, Willis is 93 and her humanistic approach to design and innovative approaches continue to shape the architectural world.