Optima® delights in celebrating the visionaries of modern architecture, individuals whose innovative designs have profoundly impacted the spaces we work and inhabit. Among these luminaries is a woman who left a remarkable imprint on her era and the course of modern architecture: Elisabeth Scott. Today, we pay homage to this trailblazer, whose architectural genius transformed the landscape of theater design.

Born in 1898 in the quaint English county of Bournemouth, Scott was nurtured within a family that recognized and fostered her creative prowess. Her odyssey began with her enrollment at the Architectural Association School in London. At the time, it was one of the few institutions breaking the gender barrier by welcoming women into its architecture program.

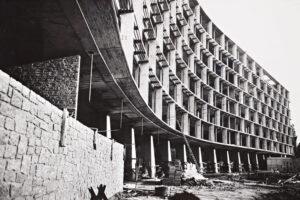

Scott’s career had a dramatic turning point when she entered the international competition for the design of the new Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, now known as the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. At just 29, Scott eclipsed nearly 70 competitors, securing her position as the youngest and the first female architect to clinch an international competition. Her triumphant design broke away from the conventional proscenium arch stage, marking a modernist departure that enhanced the intimate engagement between actors and audiences.

However, the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre was only the beginning of Scott’s illustrious portfolio. She further honed her architectural craft by designing an array of other significant structures. Among these were the Pier Theatre in Bournemouth, the Fawcett Building for Newnham College in Cambridge, and the Marie Curie Hospital in Hampstead. Each creation was a testament to Scott’s ability to envisage and realize structures that were not only aesthetically pleasing but also served the needs of the greater community.

We’re honored to pay tribute to the remarkable journey and enduring legacy of Elisabeth Scott. She dared to chart her own course in an era when the architectural field was almost exclusively male. Her trailblazing efforts underscored not just her exceptional architectural prowess but also her dedication to empowering society through conscious, innovative design.