The Life of Helmut Jahn

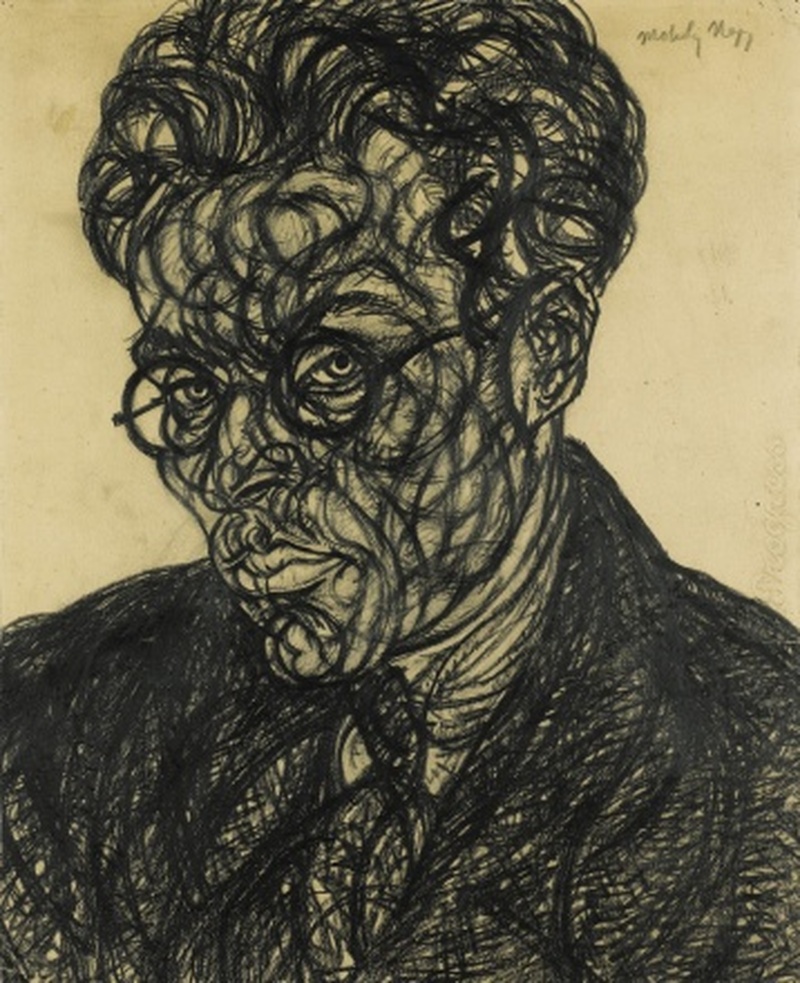

The German-American architect Helmut Jahn, who passed away in May 2021, holds a special place in the hearts of Chicagoans, as he made the city his home throughout his stellar international career. He was also a close friend and colleague of Optima founder, David Hovey Sr., FAIA.

Born in 1940 near Nuremberg, Germany, Jahn witnessed the destruction — and later reconstruction — of the town where he grew up during and after World War II. Because of this intimate and personal experience, he was inspired to study architecture and design as a way to participate in the process of stabilizing and beautifying the places where people live.

Jahn moved to Munich to study architecture, and relocated to Chicago in 1966 to further his studies under renowned architects Myron Goldsmith and Fazlur Khan at IIT. His career was forged when joining C. F. Murphy Associates, which was renamed JAHN in 2012 following Charles Murphy’s retirement.

Much of the work Jahn created took inspiration from the modern aesthetic he adopted while at ITT; he also pulled from the influences of postmodernism, the Art Deco style of the ‘30s and eclecticism throughout his career. In the late 1970s and early ‘80s, Jahn’s mark on architecture really began as he transitioned from smaller projects to legacy-defining skyscrapers.

The Works of Helmut Jahn

James R. Thompson Center, Chicago

In 1985 Jahn designed the State of Illinois Building (renamed the James R. Thompson Center in 1994), located in Chicago, which serves as the second home to the Illinois state government. From the moment its doors opened to the public, it became one of Jahn’s most controversial designs, with mixed reviews that ranged from unabashed praise to outrage.

The building, with a grand atrium at its center, has a distinctive circular shape that references the Illinois State Capitol building in Springfield. While the structure was considered futuristic at the time, in part due to the use of advanced architectural tectonics, it also incorporated design elements that were reminiscent of the grandeur of large public spaces of the past.

Over the years, many of Illinois’ most senior officeholders (including governors) have proposed selling the structure, much to the criticism of architects and architecture devotees concerned about the building’s future. And while the future of the building remains in question, the 17-story structure is internationally known and considered a momentous piece of postmodern architecture.

Sony Center, Berlin

Built in 2000 at the Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, Germany, the Sony Center stands as one of Jahn’s more recent architectural feats. After the city’s ruin during WWII, the original site — the infamous Nazi People’s Court — was stuck in the Berlin Wall’s No Man’s Land, and was left to decay. Once the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the city looked to rehabilitate much of the forgotten architecture.

Jahn undertook the project of this transformational urban marketplace with a desire to honor the meaning of building on and around abandoned structures. In the process, he successfully blended historic remnants and modern aesthetics to create an open, free-flowing space for all to enjoy.

The grouping of eight buildings that makes up the Sony Center are a mix of residential, commercial and public space. Each structure is enveloped in glass, directing the flow of light and augmenting the feeling of transparency throughout the complex. The 102 meter-long roof that sits atop the complex, built by Waagner-Biro, has become an iconic feature in its own right. The medley of steel, glass and translucent fabrics, which is often illuminated in bright colors, furthers the fluid design that Jahn intended.

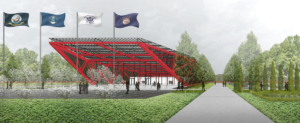

Pritzker Military Archives Center

The Pritzker Military Archives Center located in Sommers, Wisconsin, is one of Jahn’s final projects. The construction, which started in 2020, is taking place in conjunction with the development of a new Memorial Park Center. The center will advance the mission of the Pritzker Museum and Library to restore and preserve their ever-expanding collections.

The state-of-the-art structure will feature an immersive 9,400 square-foot Gallery Center open to the public. The Gallery will house artifacts and exhibits provided by the parent museum and library located in Chicago. The front of the building will feature floor-to-ceiling glass frames that illuminate the interior. Brilliant red steel beams will stretch beyond the facade, creating a dramatic rooftop extending boldly beyond the building’s entrance.

Construction on the Pritzker Military Archives Center is underway and moving swiftly; the entire Memorial Park Center will take nearly a decade to be completed.

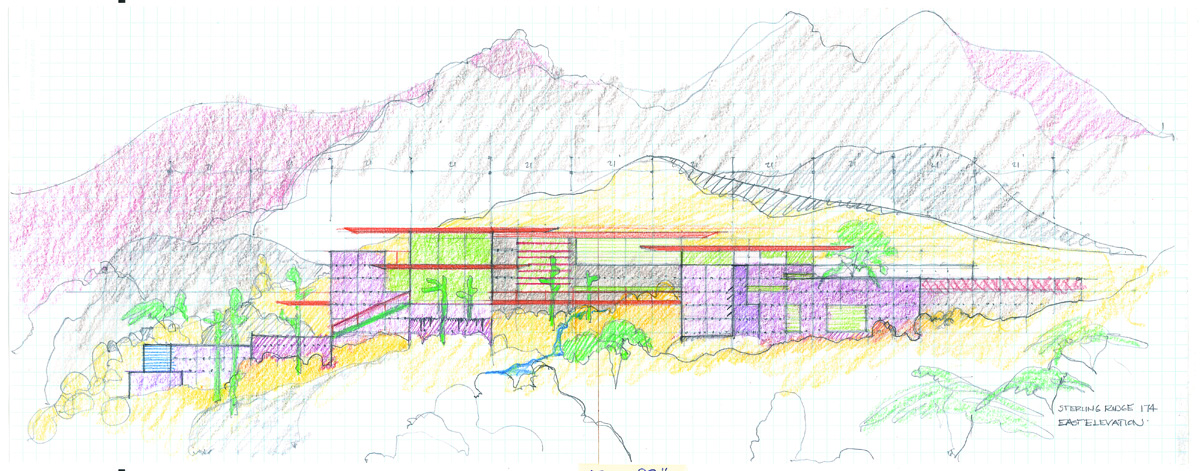

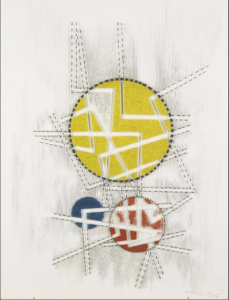

Chicago Architecture Center Exhibit

Honoring Jahn’s accomplishments and extraordinary engineering feats, the Chicago Architecture Center (CAC) has curated the exhibit Helmut Jahn: Life + Architecture. The exhibit includes an expansive compilation of ephemera including photography, sketches and models of Jahn’s most iconic works.

For those interested in learning more about Jahn’s exemplary career in architecture and beyond, Helmut Jahn: Life + Architecture is free with admission to the CAC. The exhibit is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily until October 31. You can purchase vouchers and learn more about future exhibits here.