Perhaps one of the most well-known architects of her time, especially in Chicago, Jeanne Gang is the founder and leader of Studio Gang. Born 1964 in Belvidere, Illinois, a small town on the northern border of Illinois, she was raised with the prairies of the midwest and proximity to Chicago’s architectural legacy.

Gang studied at the University of Illinois before going on to earn a Master of Architecture with Distinction from Harvard Graduate School of Design. After Harvard, she studied abroad in Switzerland and France as a Rotary Fellow before joining Dutch architect and design theorist, Rem Koolhaas and his architectural firm, OMA in Rotterdam.

In 1997, she established Studio Gang, her own practice headquartered in Chicago. The studio’s mission is to use design to connect people to each other, their communities, and the environment. Soft details that reflect the light of the lake and suggest rippling columns of water can easily be identified as Studio Gang’s work.

Studio Gang Around Chicago

Much of Gang’s work is a prominent part of Chicago’s landscape. Her designs can be found across the city, from O’Hare International Airport to the Loop to Uchicago dorms. Over the years, the studio’s work has become integral to Chicago’s rich architectural legacy. Gang’s 2010 Aqua Tower, situated at 225 N Columbus Dr in downtown Chicago, takes inspiration from terrestrial topography. The facade emulates the contours of a topographic map and reflects light in a way similar to the wave patterns of Chicago’s Lake Michigan. The tower combines a hotel, offices, apartments, and a green roof into a vertical community that facilitates human interaction.

In addition to the studio’s practice, Studio Gang is a strong supporter of climate action. As a member of the Active Transportation Alliance and Architects Advocate Action on Climate Change, the firm supports sustainable forms of transportation in urban environments and radical change in the building sector in regards to climate.

In effort to take climate action, Studio Gang has submitted a design to the C40 Reinventing Cities competition titled Assemble Chicago, a carbon-neutral residential community next to the main branch of Chicago’s public library. The proposed project would provide housing for the downtown workforce including those who earn as little as minimum wage. The design is also eco-conscious and works to reduce carbon pollution, minimize waste, and promote urban biodiversity.

Studio Gang in the World

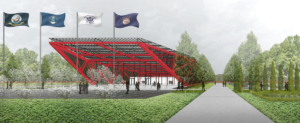

Jeanne Gang’s designs can be found across the globe from a powerhouse in Beloit, Wisconsin to the Kaohsiung Maritime Cultural & Pop Music Center in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Wherever their location and whatever their purpose, the structures focus on immersing themselves in their environment both aesthetically and through their contributions to their ecosystems. Gang’s designs take inspiration from the topography and ecology of their surroundings and concern themselves with how they can bolster the environment and human communities around them, creating the perfect harmony between architecture and nature.

The thoughtfulness of Studio Gang’s work has been recognized by receiving numerous awards.

- MacArthur Fellowship, 2011

- Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s National Design Award for Architecture, 2013

- Named Woman Architect of the year by Architectural Review, 2016

- Royal Institute of British Architects International Fellowship, 2018

Gang currently serves as a Professor in Practice at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and lectures frequently around the world. Her studio continues to present unique and conscious designs to the architectural landscape, working to build a sustainable future and sustainable communities.