As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re sharing the story of Violeta Autumn, whose distinguished career was committed to environmental protectionism and inclusion in the industry. Autumn’s designs earned her numerous accolades and recognition, and her work serves as an inspiration for architects today. Learn more about her life and career below.

The Life of Violeta Autumn

Violeta Autumn was born in 1930 Chiclayo, Peru to Russian Jewish immigrants and lived there until her family relocated to Oklahoma when she was 14. After graduating high school, Autumn attended the University of Oklahoma, where she studied under the legendary architect Bruce Goff and became the third woman to graduate from the school with a Bachelor of Architecture in 1953. In her future work, Autumn took inspiration from Goff’s use of organic design.

After completing her education, Autumn traveled across Europe during the summer, where she met her husband, Sanford Autumn, a psychologist. Autumn and her husband relocated to the San Francisco area after returning from Europe, and she obtained her California architect’s license soon after, in 1957.

Notable Works and Achievements

Autumn’s architectural experience began with preparing construction drawings for Harold Dow, a Palo Alto-based architect. For several years, she illustrated renderings and designed murals for other architects and authors, but in 1959 she ventured out on her own, designing and building her own home and architectural studio in Sausalito, California as a first project. As her design vocabulary evolved, she continued to draw from other architects she worked with and admired, including Frank Lloyd Wright (with whom she apprenticed) and John Lautner, who went on to have a stellar career as a modernist architect in South California.

Autumn worked with engineer Haluk Akol to translate organic architecture philosophies into the home’s vertical cliff site. The building featured exposed concrete buttresses to stabilize the unique structural system, a two-story copper hood for its fireplace and unstained redwood. After its completion in the early 1960s, the home was widely celebrated, including features in Progressive Architecture and Look magazines.

Autumn received her U.S. citizenship in 1963 and quickly became involved in aspects of local government, from joining her local Community Appearances Advisory Board to being named commissioner of the Planning Commission and to becoming a Sausalito City Councilwoman. Much of her work in public office mirrored her philosophies in architecture. She became largely known for her strong environmental protectionism along with the redevelopment of a host of important waterfront projects in the San Francisco Bay area.

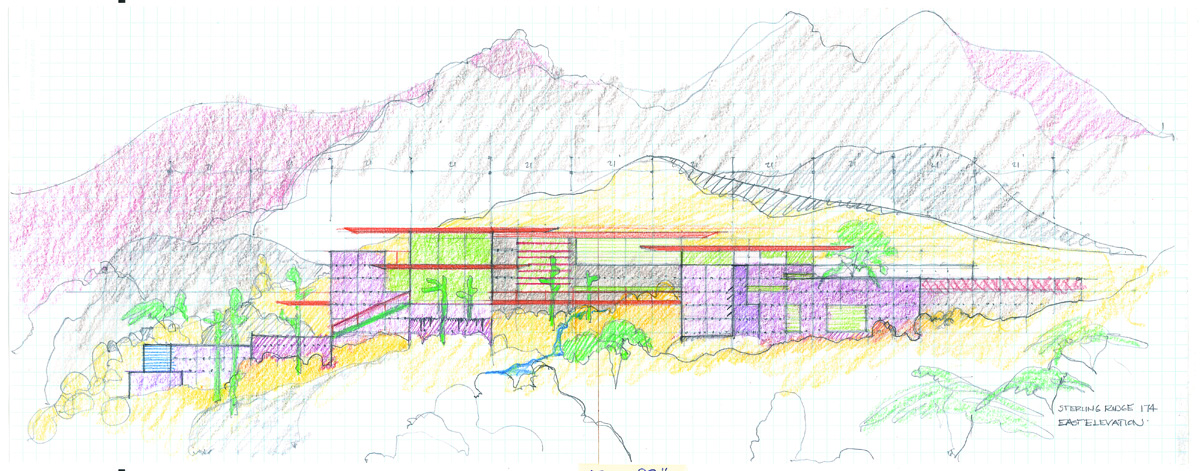

Following her career in local government, Autumn partnered with fellow University of Oklahoma architectural graduate John Marsh Davis to create Davis-Autumn & Associates. Together, the two completed a host of projects, many of which are wineries still in existence in Sonoma and Napa Valley today, including Joseph Phelps Vineyards, Rutherford Hill Winery, Sullivan Vineyards and their most acclaimed, Souverain Winery. Designed and opened in 1974, the Souverain Winery won the American Institute of Architects Bay Area Honor Award for Design Excellence.

Violeta Autumn’s contributions to the field of architecture have left an indelible mark. Her work helped pave the way for future generations of practitioners who strive to create innovative, environmentally-friendly designs that prioritize community and inclusivity.