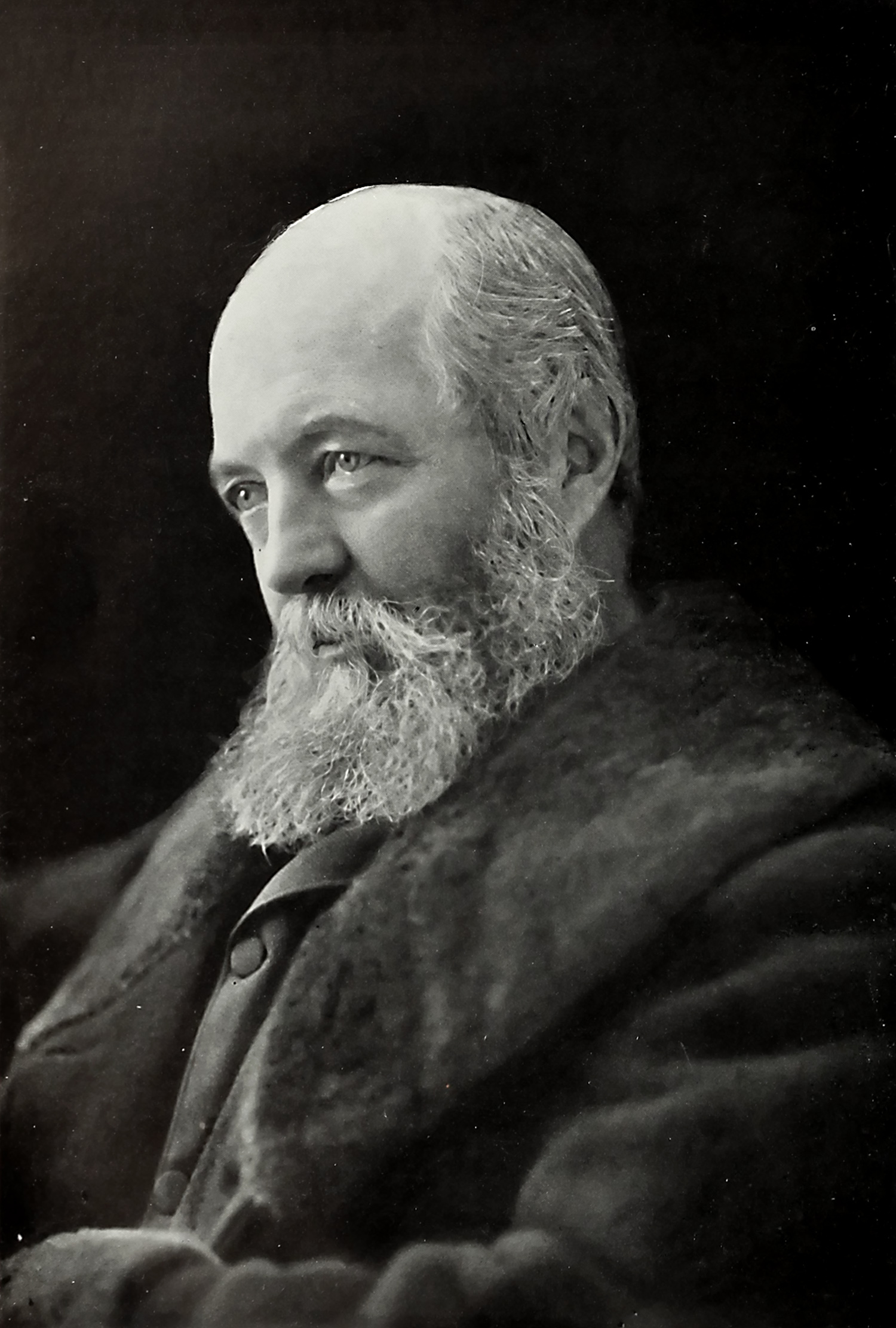

Even if you haven’t heard the name of Frederick Law Olmsted before, there’s no doubt you’ve come across his work. If you’ve ever visited Central Park or read about Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, you’ve seen Olmsted’s fingerprints across urban design. Olmsted was an American landscape architect, journalist, social critic, and public administrator. Widely considered to be the father of American landscape architecture, Frederick Law Olmsted’s life and work were vastly impactful to cities across the world.

From a young age, Olmsted was immersed in greenery. He was born in Hartford, Connecticut in1822, and his father had his own interests in nature, people, and places. Olmsted lived on a farm for years before deciding on a career in journalism, which took him over to England. There, his visits to public gardens sparked inspiration that would form his later works. His profession in journalism would take a sudden turn in the 1850s, with the help of his mentor, Andrew Jackson Downing.

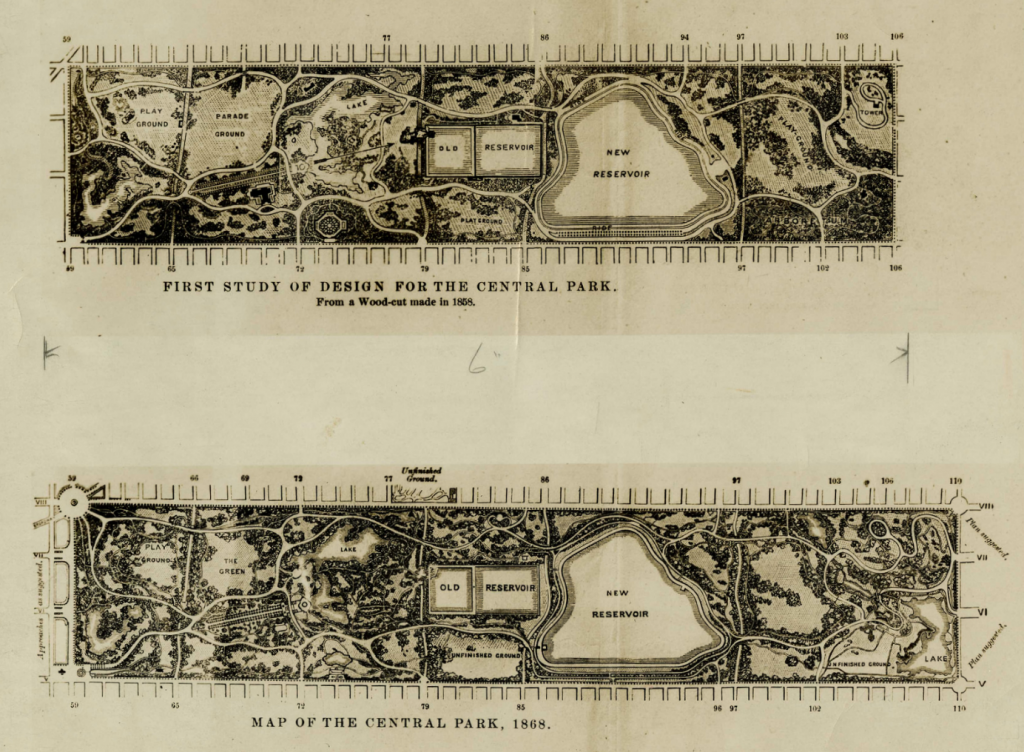

Downing was a landscape architect himself, and was one of the first to propose developing New York’s Central Park. He introduced Olmsted to English-born architect Calvert Vaux and their plans for the vast green space. Tragically Downing passed away, and Olmsted was left to fill his shoes in presenting their design. Prior to this, Olmsted had never created or executed a landscape design, but his theories and political contacts were invaluable. With the Central Park project won, Olmsted’s name began to explode across the industry.

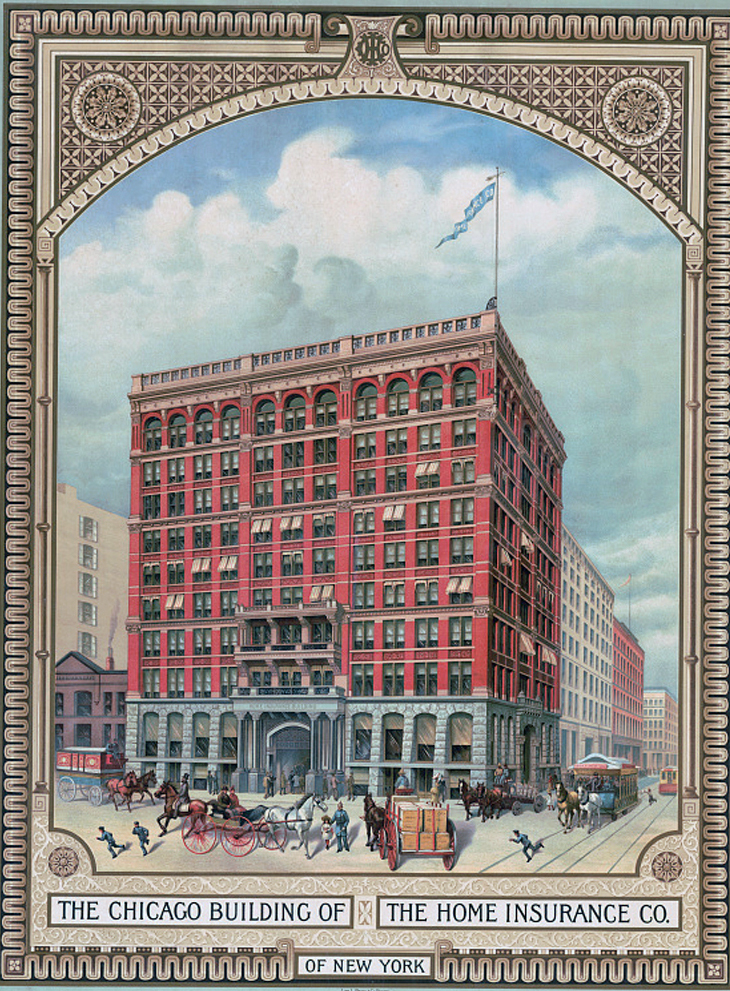

Over the years, Olmsted worked on the designs for Prospect Park in New York City, Walnut Hill Park in New Britain, Connecticut, Cadwalader Park in Trenton, New Jersey and more. His reach extended into larger urban planning initiatives, such as the country’s first coordinated system of public parks and parkways in Buffalo, New York and the country’s oldest state park, the Niagara Reservation in Niagara Falls, New York. Olmsted also had a large impact on the city of Chicago; his design for Jackson Park, Washington Park and the Midway Plaisance are still in existence today.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s legacy on American landscape and urban design is a lasting one, and his work a medium of art all its own. As his fellow Chicago planner colleague and friend, Daniel Burnham, once said, “an artist, he paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest covered hills; with mountain sides and ocean views.”