At Optima, we’re in constant pursuit of better and smarter ways of creating, which is why we often employ prefabrication, from our multifamily properties to our desert dwellings. Prefabrication describes the process of building elements off-site in a factory or workshop, and then later fitting those elements together on-site. This carefully calculated process has revolutionized the industry, allowing builders to cut down on time, cost and labor needed to create a structure. To understand just how vastly the industry and the way that we build has transformed, we’re taking a deep-dive into the world and history of prefabrication.

Early Origins

Naturally, the idea of building pieces separately before putting them all together in place is centuries old. Prefabrication is inspired by building techniques that date as far back as Mesopotamian civilization and Roman fort-building. In fact, the earliest known example of prefabrication comes from around 3800 BC, when the oldest engineered roadway, the Sweet Track in England, was built using timber sections that were constructed off-site.

Prefabrication techniques were used to erect giant structures in Sri Lanka, to rebuild the Portuegese capital after the great Lisbon earthquake of 1755 and even in 19th century Australia, when a large number of prefabricated houses were imported from the U.K. No matter the circumstances, from building large to building wide, the streamlined technique allowed for increased control, lowered cost and expedited process.

Industrialization and Modernism on the Rise

Prefabricated farm buildings and bungalows were the first readily available structures on the market, around since the early 19th century. Most notable during that time was London carpenter Henry Manning’s prefabricated Portable Cottage, which was transported to Australia. Affordable housing was created using the technique, too, supplying homes for 49ers during the 1848 California Gold Rush and to refugees of war during World War II.

Prefabrication was also an integral tool in rising Modernist architecture. The first ever Modernist structure, The Crystal Palace designed by Joseph Paxton, was built in 1851 using this method. Like The Crystal Palace, Modernist design was rooted in materials such as exposed steel and glass, which were perfectly suited for prefabricated builds as they were most often used in the simple and functional Modernist structural patterns.

Prefab Concrete and Steel

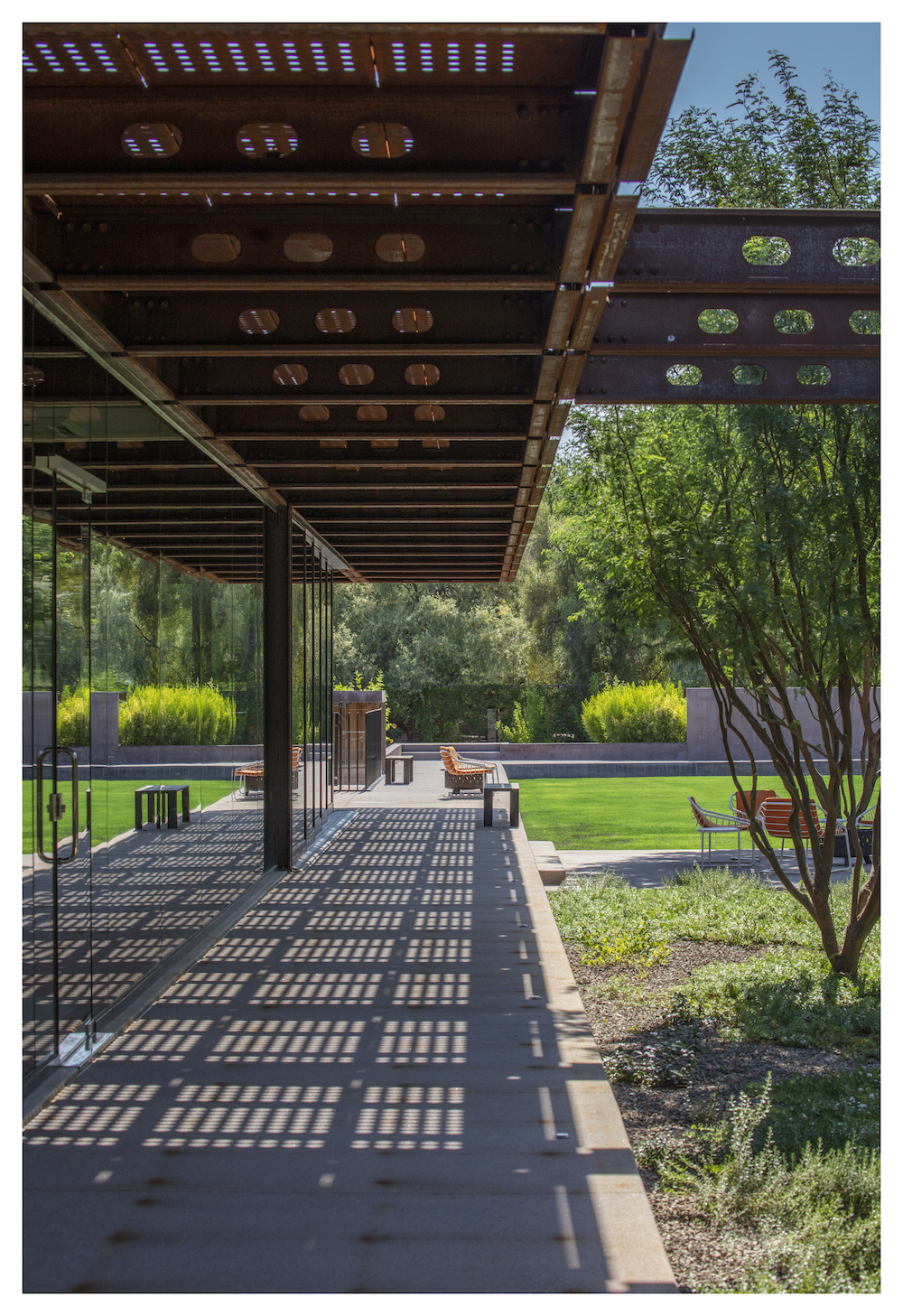

As the prefabrication practice continued to grow, technical developments such as the development of sheet steel, the improvement in alloys, the use of lightweight aggregates and the promotion of precast reinforced concrete pushed the field even further. Concrete and steel in particular proved to be highly efficient materials in the prefabrication process, with pre-poured concrete allowing for more flexibility, and prefabricated steel sections reducing in-field risk during cutting and welding. These components have proven especially crucial to simplifying the construction process in buildings where a particular part or form is repeated numerous times.

Created by Optima President David Hovey Jr., Optima DCHGlobal has created The Optima DCHGlobal Building System, a patented prefabricated architectural system that is flexible in both horizontal and vertical directions, sustainable up to the net-zero level, multi-generational, and able to be built quickly and efficiently in any location, climate or terrain.

His invention of this system has created award-winning residences, such as Relic Rock and Whale Bay House. We continue to utilize the latest in steel technology, and often employ elements of concrete, to create our simple yet stunning Modernist structures.

As we continue to look forward to a future of innovating and finding new ways of creating, we are humbled to look back at the history of prefabrication and how the technique has grown, allowing us to grow, too.