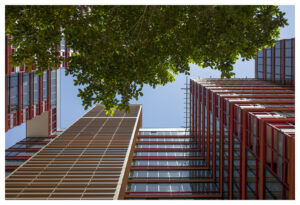

Art and architecture share a rich, timeless connection rooted in their design, creators and intended meaning. Both forms of expression become envisioned and constructed through similar principles, visual elements and ambition to engage with one’s senses. Today, we’re exploring this essential relationship and what happens when the two worlds collide.

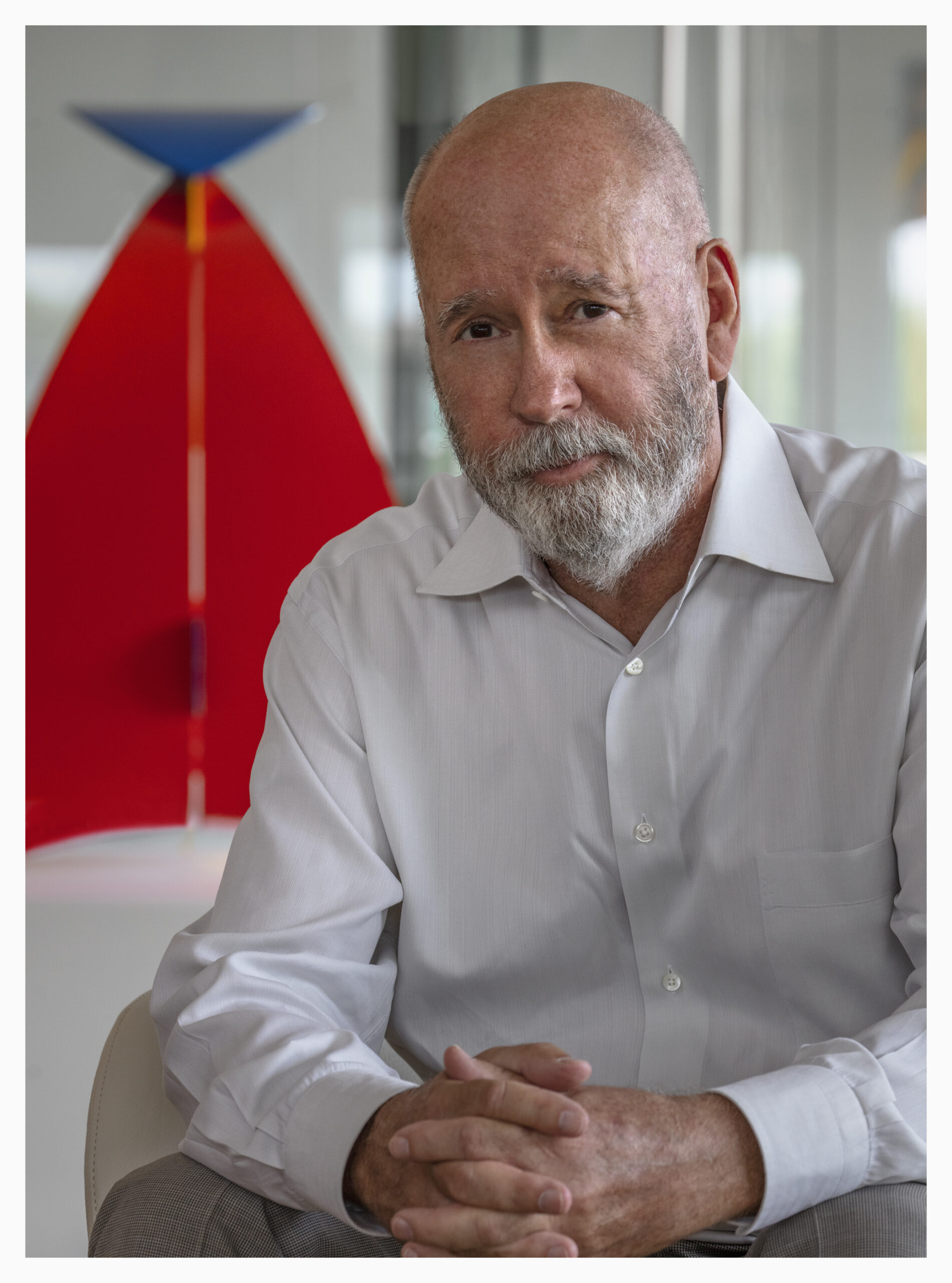

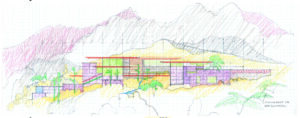

David Hovey Sr., FAIA, Optima’s CEO and Founder, says it best when describing the linkage between art – in particular, sculptures – and architecture, saying that “architecture is about function, as well as aesthetics, while sculpture is really just about aesthetics.”

Architecture is traditionally informed by functionality first, with aesthetics coming into play as with a significant role. Art, on the other hand, is commonly guided by aesthetics, without any burdens to deliver an object or outcome that is functional. However, both forms of expression are typically influenced by similar social and political factors that affect the environment surrounding the work or structure.

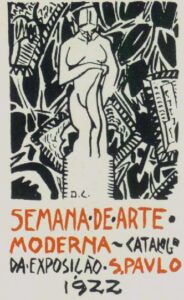

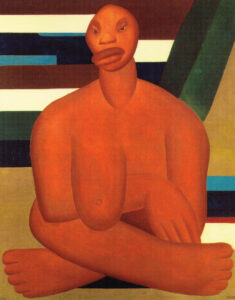

Centuries-old cultural movements, including the Renaissance, where art imitated life and vice versa, demonstrate the linkage between art and architecture. However, it wasn’t until the Avant-Garde movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the integration of the two took a new meaning.

This integration between the disciplines quickly became a core characteristic of modernism and modernist design, and is distinctly present in the work of some of the greatest architects and artists of the time period. Because artists use their art as a tool to shape emotions, modernism emerged as an expectation in which art and architecture would provide a new value when combined.

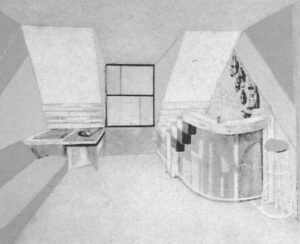

The Bauhaus Movement was one of the first to introduce this idea, encouraging the unification of all arts and coupling aesthetics with the technology of the time. Notably, this ideology was cultivated through Le Corbusier’s use of painting and sculpture within his established concepts of architecture. Le Corbusier also argued that it was of equal importance to architects, painters and sculpturists to contribute constructive collaborations to the world by designing and creating in harmony with one another.

Along with Le Corbusier, various other artists throughout the past century have tried to synthesize art and architecture throughout their work, particularly Oscar Niemeyer, Mies van der Rohe and Zaha Hadid. Today, architects and artists continue to collaborate and integrate their disciplines more than ever, exploring and expanding the dynamic relationship shared between the two.