At Optima, we’re believers that exceptional design has the power to inspire awe and wonder, and to enhance the human experience. One such component of design, the plaza, is a perfect example of this: designed as an open, public space, plazas create hubs for community activity and human connection. To learn more about the role this seminal piece of design has in creating public space, we’re diving into the history of the plaza.

The First Plazas

From colonial cities in Spanish America to the Spanish East Indies, there were several types of plazas serving as the center of community life. The plaza mayor often referred to the space centered between several administrative, religious and government buildings. The plaza de armas, meanwhile, served as a rallying space for troops, and the plaza de toros translates, quite literally, to bullring.

Perhaps the most significant example of such plazas is the Plaza Mayor in Madrid, Spain. Dating back to 1619, the plaza was constructed during the reign of Philip III by architect Juan de Herrera. Though the plaza saw several disasters since then and was reconstructed an equal number of times, it remained (and still remains) a pivotal public fixture in Madrid. Plaza Mayor has served many diverse purposes, from being the site of a marketplace, to bullfights, to military parading ground, to public executions, to even trials during the Spanish Inquisition and crowning ceremonies.

Evolving over time to a space of leisure, the Plaza Mayor is now the site of outdoor cafes, restaurants and, inevitably, tourists. It draws people in with yoga workshops, concerts and festivals — a far cry from its dabbles in militant history. The Spanish plaza is also related to the Italian piazza, with both belonging under the umbrella term “town square,” which includes city squares, plazas, piazzas and city greens.

The Modern Day Plaza

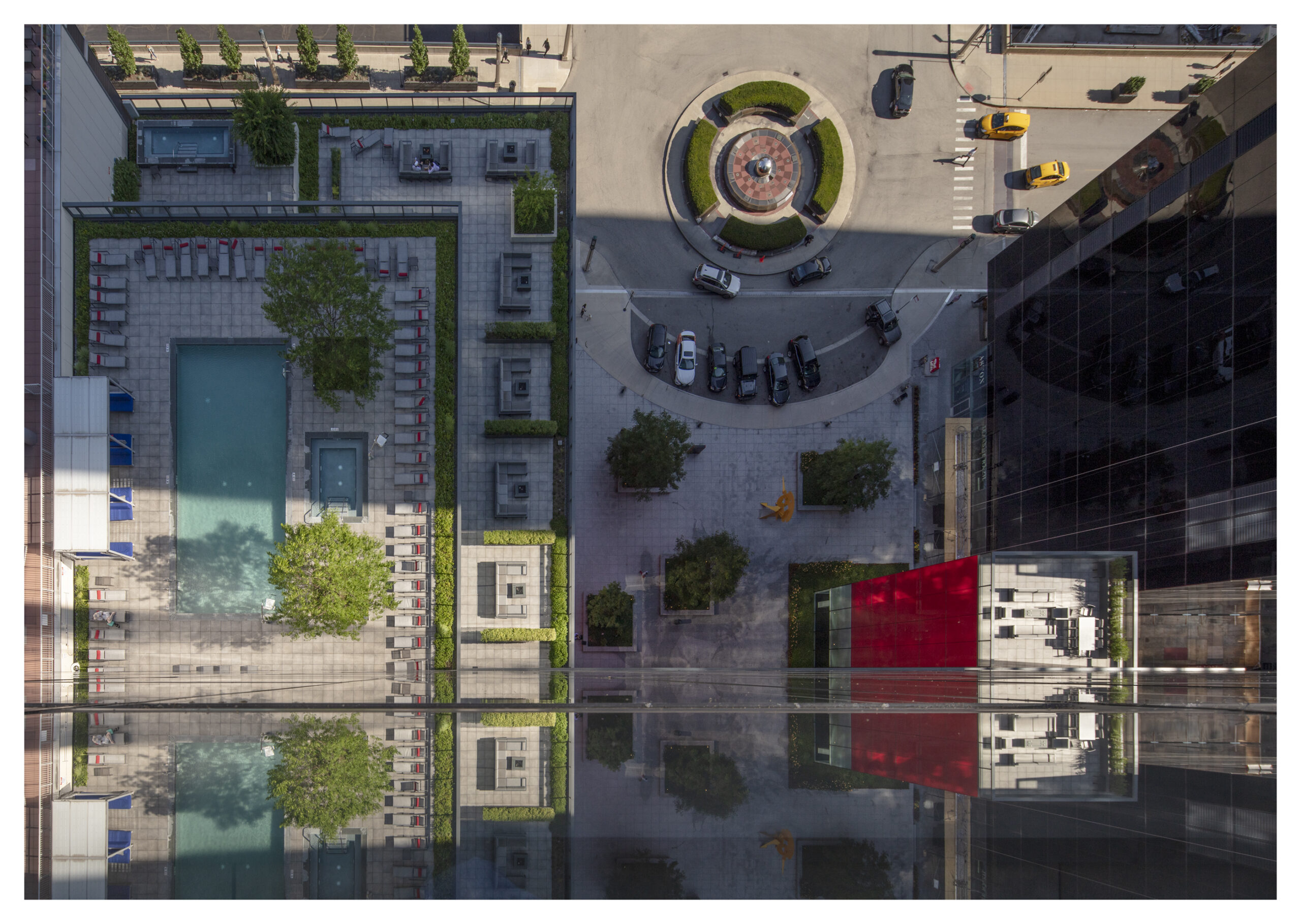

Following in the footsteps of Madrid’s adaptable Plaza Mayor, the modern day plaza can refer to a multitude of spaces with a multitude of purposes. Within our own portfolio, a prime example of a plaza is at Optima Signature and Optima Chicago Center. By sliding the podium of Optima Signature North and juxtaposing Optima Chicago Center to the West and South, the buildings create a dynamic plaza space, which features lush landscaping, planters and benches. Kiwi, a large-scale sculpture designed by Optima founder David Hovey Sr, adds to the visual energy of the space.

Now, plazas refer to open spaces within neighborhoods that boost economic vitality, pedestrian mobility and safety as well as providing aesthetically pleasing areas. No matter the interpretation of the word, there’s always one belief at the core, and that’s gathering and celebrating community.