From well-known figures like Charlotte Perriand to lesser-known names like Eileen Gray, countless women have left their mark on the history of architecture. As part of our Women in Architecture series, today we’re taking a look at another pioneering figure: Norma Merrick Sklarek, a woman who paved the way for generations of African American woman architects to follow.

Norma Merrick Sklarek

Norma Merrick Sklarek was born on April 15, 1926, in Harlem, New York. Her parents were both immigrants from Trinidad; her father was a doctor and her mother was a seamstress. Sklarek grew up going to predominantly white schools, where she excelled in math, science and fine arts, encouraged by her father. In fact, he was the one who initially suggested she pursue a career in architecture.

Sklarek pursued education at Barnard College for a prerequisite year before enrolling at the School of Architecture at Columbia University. Her experience was challenging, but nevertheless she persisted and went on to graduate in 1950 as one of two women and the only African American in her class.

Career and Work

After graduation, Sklarek faced both gender and racial discrimination in her job hunt and was rejected by nineteen firms. She told a newspaper in 2004, “They weren’t hiring women or African Americans, and I didn’t know which it was [working against me].” She took on a civil service job as a draftsperson for the city of NY, but refused to settle. While working for the city, she took the architectural licensing examination in 1954 and became the first licensed African American woman architect in the state of New York. (Later, this accomplishment would earn her the nickname “the Rose Parks of Architecture.)

As a single mother, Sklarek’s own mom watched her kids while she worked at a variety of architectural firms. The first cordoned her to menial tasks, such as designing bathrooms, while the second gave her more responsibility. At her third firm job, Sklarek noticed her supervisor was particularly scrutinous of her. She carpooled with a white male colleague who was consistently late to work; her boss critiqued Sklarek’s own punctuality but never made mention of the man’s. In response, Sklarek bought her own car.

In 1959, she became the first African American woman member of the American Institute of Architects and in 1960, the first Black woman licensed as an architect in California. Sklarek rose in rank at her third architectural firm job, overseeing other staff and production processes. Like many women in the field, she remained cordoned to project manager positions, rather than becoming a project architect, despite her aptitude and keen sensibilities.

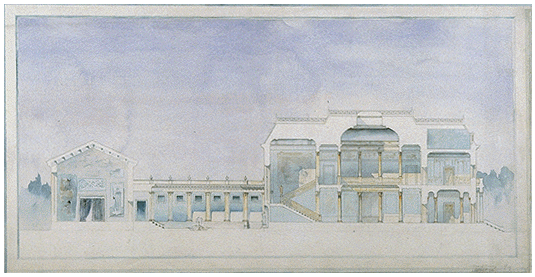

She worked on prestigious projects such as the California Mart, Fox Plaza, Pacific Design Center, San Bernardino City Hall, and the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. She also continued to accumulate accolades throughout her career, including becoming the first African American woman elected to the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects in 1980. Five years later in 1985, Sklarek co-founded Siegel Sklarek Diamond, the largest woman-owned architectural field in the country and became the first African American woman to co-own an architectural practice. Throughout her lifetime, she served on numerous boards, became an esteemed educator and prioritized mentoring other aspiring architects. She was proud to be a role model for others, acting as a figure that she herself had not had access to on her own journey.

Norma Merrick Sklarek was a pioneer of her own time, and remains today a figure of inspiration for anyone who faces discrimination and prejudice in their field. She proved that you are not what others believe you to be, and fought for others to be able to step into their full potential and leave their own marks on the architectural world.