As part of our ongoing “Women in Architecture” series, we’re thrilled to spotlight Tatiana Bilbao, a visionary architect whose work blends traditional Mexican culture with modern design. Her innovative approach to architecture not only transforms landscapes but also enriches communities. Bilbao’s contributions to architecture are not just about buildings but about creating spaces that foster human connection and cultural identity.

Tatiana Bilbao was born in 1972 in Mexico City, a city rich with cultural heritage and architectural diversity. Her journey into architecture was influenced by her family, particularly her grandfather, who was an architect. Growing up, she was surrounded by discussions about architecture and design, which naturally led her to pursue a career in the field. Bilbao studied architecture at Universidad Iberoamericana, one of the leading private universities in Mexico. After graduating in 1996, she worked at the Urban Housing and Development Department of Mexico City and later co-founded the architectural think tank LCM.

Founding Tatiana Bilbao Estudio

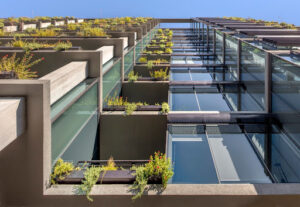

In 2004, Bilbao founded Tatiana Bilbao Estudio with the aim of integrating social values, collaboration, and sensitive design approaches into architectural solutions. Her practice is known for its focus on sustainability, social housing, and culturally relevant design. Bilbao’s philosophy centers on the idea that architecture should respond to the environment and the needs of its inhabitants, rather than imposing a predetermined aesthetic.

Tatiana Bilbao’s portfolio is diverse, ranging from social housing projects to large-scale urban developments and private residences. One of her most notable works is the Ajijic House, a project that showcases her ability to blend modern design with traditional Mexican elements. Located on the shore of Lake Chapala, this house features large windows that frame stunning views of the lake and mountains, and materials that reflect the local culture and landscape.

Another significant project is the Monterrey Pilgrim Route, a master plan for a religious pilgrimage route in Mexico. This project underscores Bilbao’s talent for integrating architecture with natural landscapes and cultural traditions. The route includes chapels, plazas, and lookout points, designed to enhance the spiritual journey of pilgrims.

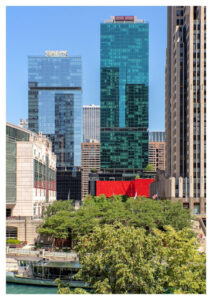

Bilbao’s commitment to social impact is evident in her affordable housing projects. The Sustainable Housing Prototype is a notable example, designed as a low-cost, flexible housing solution for rural communities in Mexico. This project was showcased at the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial, where it received widespread acclaim for its innovative approach to social housing.

In addition to her built works, Bilbao has been a prolific contributor to architectural discourse through her teaching and publications. She has taught at various prestigious institutions, including Yale University, Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, and Columbia University.

Tatiana Bilbao’s work has earned her numerous awards and recognitions. In 2012, she received the Kunstpreis Berlin, an award that honors outstanding contributions to the arts. In 2019, she was awarded the Marcus Prize for Architecture, recognizing her innovative work and significant contributions to the field.

Bilbao has also been honored with the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, which celebrates architects who address issues of sustainability and social responsibility. Her inclusion in the 2019 TIME 100 Next list further underscores her influence and impact on contemporary architecture.

Legacy and Impact

Tatiana Bilbao’s work exemplifies how architecture can be a force for social good, addressing issues of sustainability, community, and cultural identity. Her designs are a testament to her belief that architecture should be accessible to all and that it should enhance the human experience.

Through her practice, Bilbao has demonstrated that it is possible to create beautiful, functional spaces that are deeply rooted in their cultural and environmental contexts. Her legacy is one of innovation, empathy, and a relentless pursuit of architecture that makes a positive impact on society.

As we continue our “Women in Architecture” series at Optima®, Tatiana Bilbao stands out as a beacon of inspiration, reminding us of the profound role that architects can play in shaping not just our built environment, but our communities and lives.